the A.T. Experience

In 1930, Myron Avery embarked on a solo hike across the Appalachian Trail while pushing a measuring wheel over the terrain. Avery, founder of the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club and chairman of the Appalachian Trail Conference for twenty-one years, was responsible for the mapping of the first official route of the A.T.

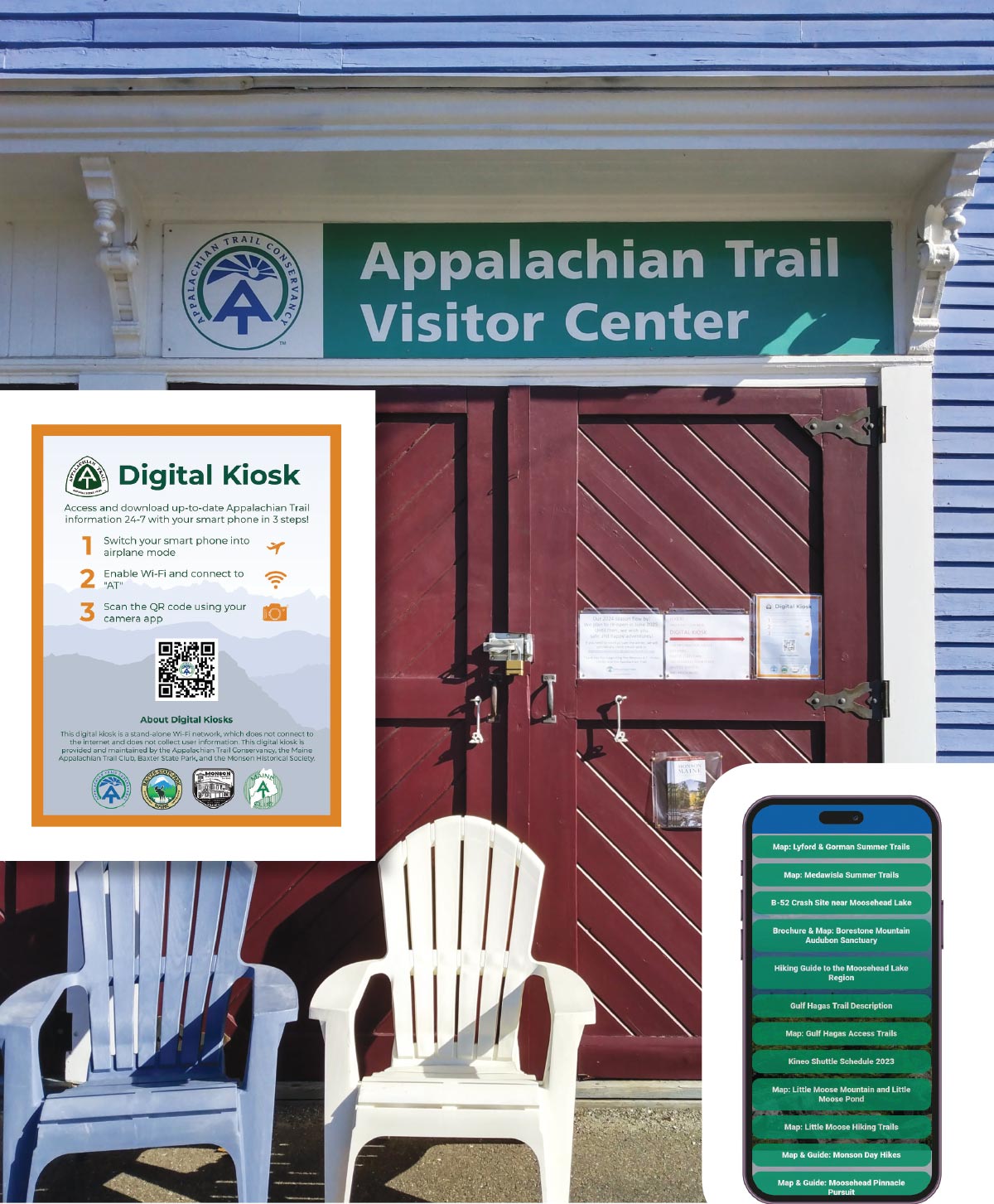

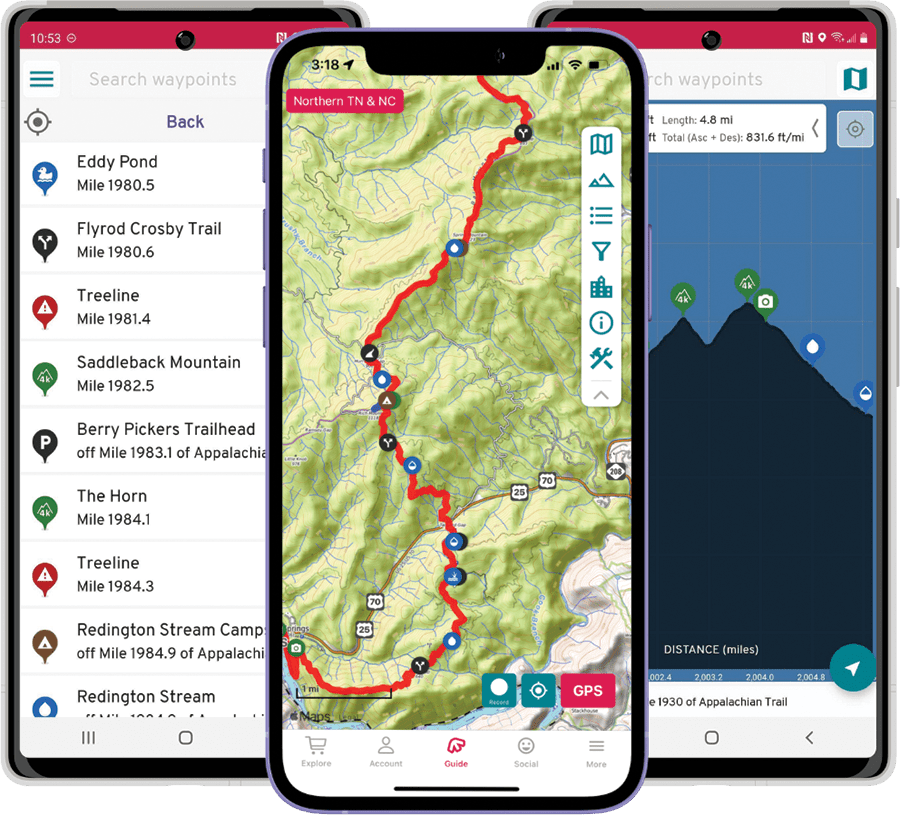

Technology has always been part of Trail history, and newer technologies such as GIS are continuing to shape how we understand and experience the A.T. GIS, which stands for geographic information system, is a computer system that collects and stores information from a variety of data sources. This information can then be displayed through maps, charts, and other visual formats, allowing users to discover relationships, patterns, and trends concerning a location. When people are looking for nearby restaurants or local traffic conditions through apps on their phones, they’re using programs made possible by GIS.

In 1998, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy used GIS to create the first “on-screen” digitization of the A.T. Much of the on-trail work was done by ATC volunteer, Dr. Vernon Vernier, who many other hikers knew as “Del Doc.” He would begin a more detailed survey several years later using high-end GPS equipment — a Trimble ProXRS with a handheld TSC1 data collector running Asset Surveyor field software, to be precise. After Vernier passed away, the work was completed by ATC members Karl Hartzell and John Fletcher.

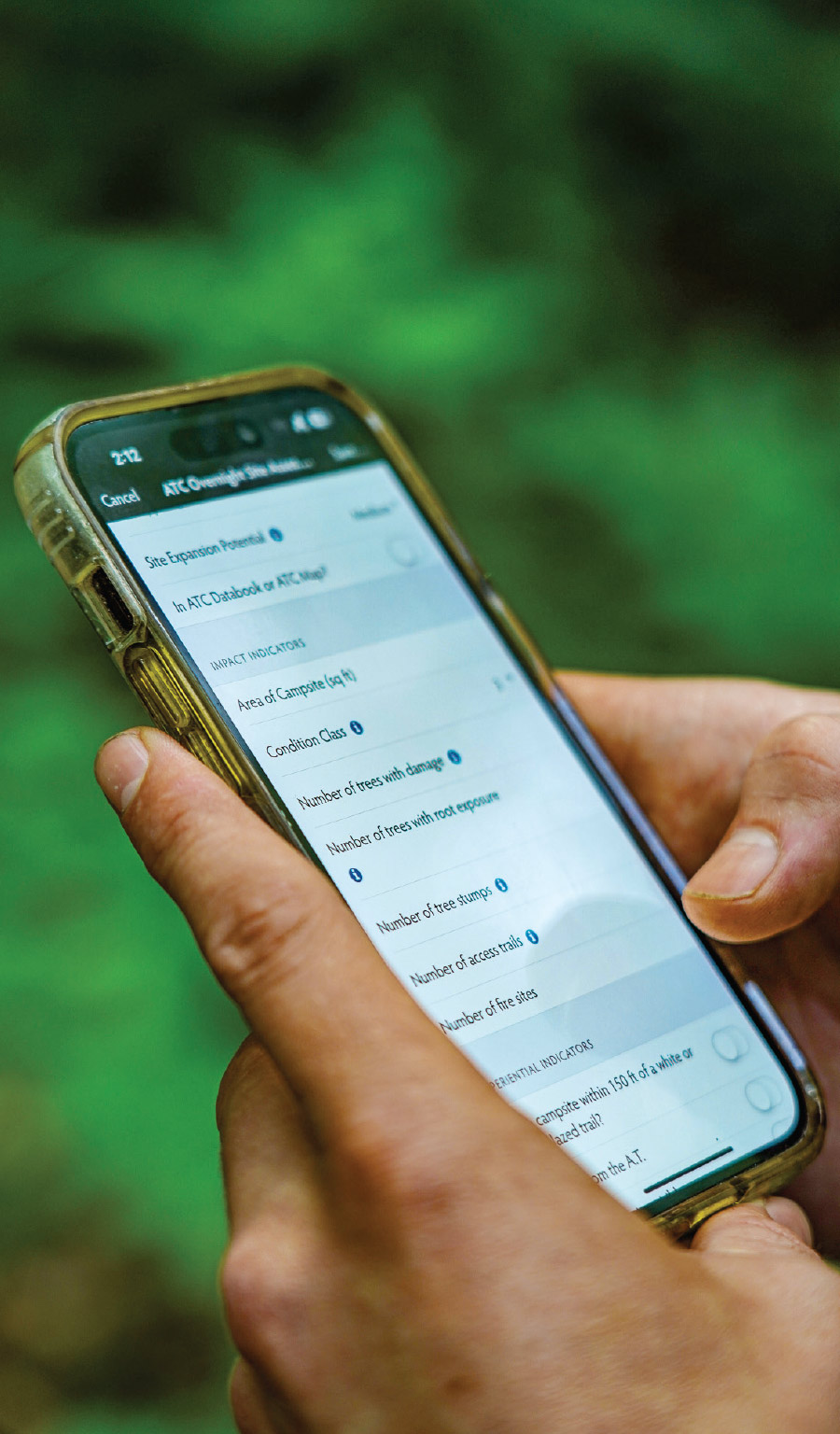

Today, the ATC is using GIS to collect visitor and Trail data in order to make management decisions, as well as to create maps. Since the A.T. is an important north-south migration corridor for wildlife, the ATC is also using GIS to assess and monitor the corridor boundaries and the rare species that inhabit and traverse the Trail.

Below: Hikers aren’t the only ones who benefit from improved Trail technology like GIS. In Pennsylvania, the A.T. crosses through 227 miles of the Kittatinny Ridge. In addition to providing clean drinking water for thousands of people, the landscape also shelters many endangered, threatened, and migratory species, including the bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii). A local conservation organization asked its partners to help incorporate their priorities into a five-year strategic plan. In response, the ATC built a GIS tool that aggregates data — from thirteen counties and around 930,000 individual properties — in order to share its conservation values. Since then, more than sixty organizations in Pennsylvania have engaged with the tool and provided important feedback. Photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The Department of Natural Resources system in Georgia is also now linked to the ATC’s ATCamp, speeding up the state’s registration process for those who have initially entered details into the ATC’s platform. The ATC set up the ATCamp voluntary registration system to allow thru-hikers to see how many other hikers have registered that season according to start dates and locations. At Amicalola, a thru-hiker can enter their ATCamp number in the state’s portal, which will then autofill much of the form. The thru-hiker information from ATCamp, as well as from Basecamp, helps ATC volunteers in managing the Trail and its shelters.

Mogilewsky also views ATCamp as a “Choose Your Own Adventure” tool for thru-hikers. “For a lot of people, being part of the community is an important part of their thru-hike experience. We offer ATCamp registration so that you can see what other people are doing in that given year. At the same time, some people hike the Trail to disconnect.”

Below: Collected data can be used by ATC staff, partners, and volunteers to improve maintenance strategies along the A.T. and the Trail corridor. Volunteers shown here are helping with native plantings at Max Patch. Photo by Anne Sentz

RIMS could also potentially have broader applications for hikers in the future. “Eventually, what we hope to do is leverage this data into something that’s easier for people to see,” says Mogilewsky. “Instead of having to log in to RIMS, they could just pull up a GIS interactive map on the ATC website and see things like locations for good solitude hikes or for a social gathering. We’ve just begun implementing RIMS, but we hope that it can be used as a tool for day hikers.”

Then came the pandemic. The number of visitors to Max Patch increased. Fences meant to keep people out of protected areas were knocked down. Vegetation was trampled, creating unsanctioned footpaths. CMC volunteers removed trash by the truckloads every week.

However, not all of Max Patch had been subject to the same bans and restrictions. As a result, there was confusion about which areas were actually open. Technology — specifically GIS technology — was used to create better maps so visitors could still enjoy the Trail.

FarOut users have found the app’s crowd-sourced information to be especially useful. “I’ve heard from hikers that the comments on water sources have been invaluable for planning their trips,” says Miller. “As someone who likes to solo hike, it’s always kind of comforting to be able to look at my day ahead to see if there are any big issues coming up, like dry water sources or busy road crossings. This can really help inform how I plan my day to day.” Adds Jackson, “It gives you that additional security blanket of current and up-to-date information from other users who are anticipating and expecting the same things that you are. So it’s nice to know what’s going on ahead.”

Naturally, hikers should be aware of not relying too heavily on apps and devices. Reception tends to be spotty in remote, mountainous areas. Phones can get wet and batteries can die. “These apps are absolutely an added benefit for visitors,” says Jackson. “But at the same time, having a map and a compass, and knowing how to use them, is essential. An app should never replace any of the ten essentials that someone brings on the Trail.”

While the protected landscape that surrounds the A.T. remains a critical carbon sink that helps to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, climate change has made sections of the Trail hotter and drier. Hikers may have noticed that there are significantly fewer water sources compared to ten or fifteen years ago. Climate change has also led to an increase in extreme weather events, such as tornadoes, high winds, drought, and heavy rain that can erode the soil, injure hikers, knock down structures and trees, and impact viewsheds. Technological advancements will help assess risks and damage and better allocate resources where they are needed.

At the 2024 MIT Chief Data Officer and Information Quality Symposium, ATC President and CEO Sandra Marra emphasized the need for applying the correct, technology-based solutions, “There are opportunities through technology that could, in fact, aggregate these multiple sources of data, at least at a fundamental level for us, and then free up [the ATC’s] limited staff and resources to start doing more sophisticated analysis.”

The ATC’s partners, clubs, and other affiliations are essential to the Trail’s protection and the growing use of new technology to do so. However, funding is also a crucial part of that growth. The ATC is currently working to expand GIS capacities through an investment initiative for data, licensing, server capacity, and dedicated staff with GIS and technical expertise. Philanthropic contributions toward a range of ATC programs can increase the pace and scale of land protection and related decisions by providing local conservation partners with up-to-date, reliable, relevant, and usable conservation and recreation data.

During the MIT symposium, Marra explained, “The Appalachian Trail was built on the concept of being a place where people can get away from the problems of living. [It is] critical that we be able to protect and continue to provide that resource and that place for people.” As the ATC adapts to emerging technologies, the Trail can be preserved for the enjoyment of generations to come.

ATLAS IT (A.T. Landscape’s Aggerated Spatial Information Tool) is one of several examples of the ATC employing GIS data and technology to support setting priorities and engaging partners in protecting specific lands. ATLAS IT is a decision-making support tool that helps conservation partners to understand how land parcels contribute to the protection of the Trail. Users can view and generate reports on these parcels according to various information layers, such as viewsheds, climate resiliency, ecological systems, cultural and historic sites, and more.

The NRCA (Appalachian Trail Natural Resource Condition Assessment) program is led by the ATC and the National Park Service to assess trends and vulnerabilities to the Trail’s natural resources and to inform management decisions. This ArcGIS Hub allows users to interact and visualize a wide range of NRCA data through story maps, apps, and web maps.

An interactive map of the A.T. was built cooperatively by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and the National Park Service using ESRI’s Arc GIS Online mapping technology and can be found here: appalachiantrail.org/map