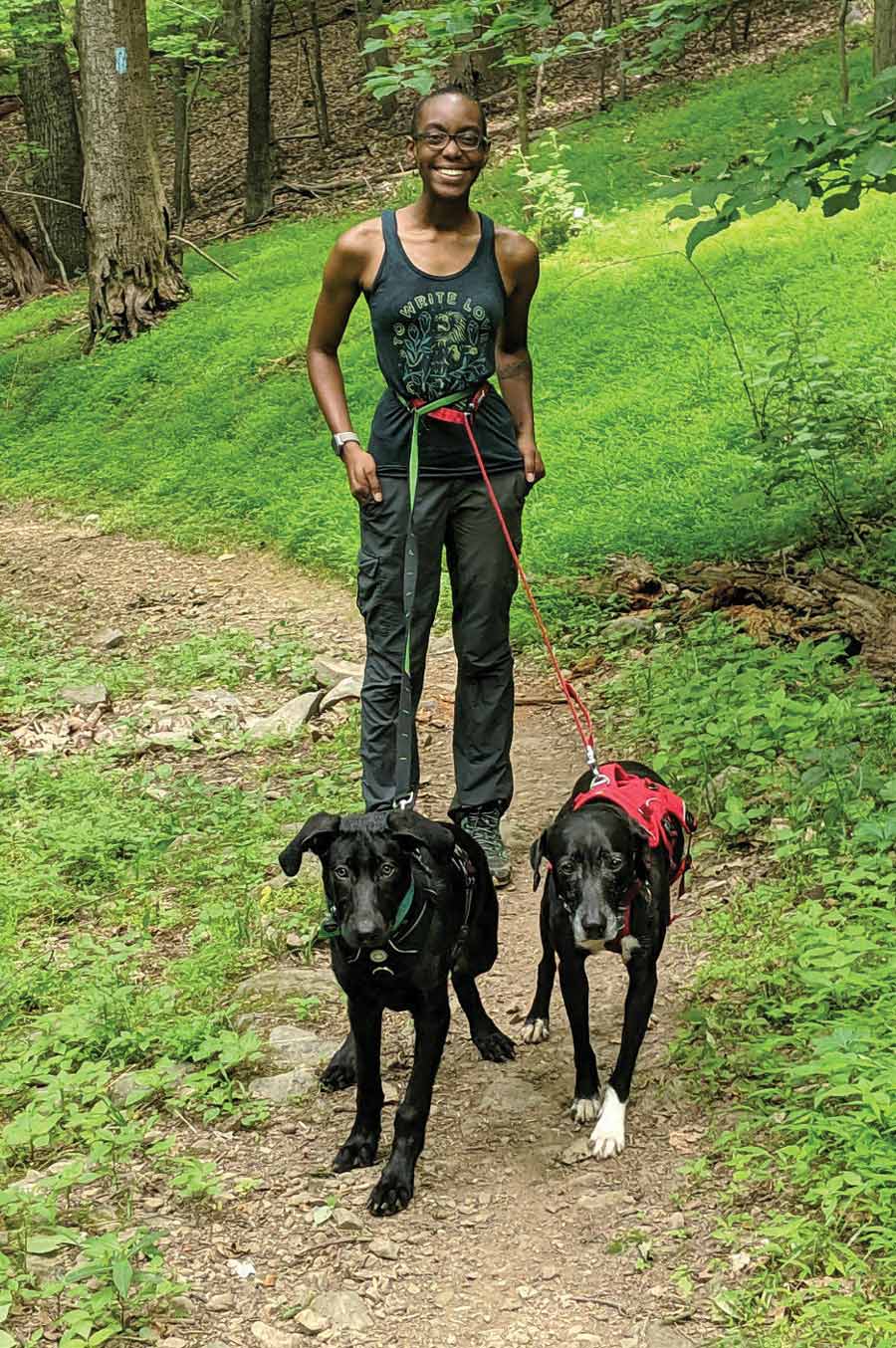

That isn’t to say that options never arose. I spent my childhood camping and hiking, but with two Army parents who were more interested in car camping than carrying gear again. When I was a trip leader at Florida Gulf Coast University, Outdoor Pursuits ran a spring break trip to hike the Trail in Georgia. Did I undertake this trip? Hard pass—too much of that “elevation” stuff. My flat land excursions were just as outdoorsy. Yet, here I am, with bits and pieces of ATC memorabilia so that as I settle into this misadventure called adulthood I maintain a piece of that community everywhere.

The easy thing would be to continue to pass off that lack of belonging as “because I’m Floridian and we don’t do that kind of outdoors.” That’s far more attractive than “because, despite how much I wish it wasn’t true, lack of representation influences me more than I’d like to acknowledge.” I didn’t see myself in the Trail community—so I chose to insert myself.

That event led to volunteering at the A.T. visitor center as regularly as my bizarre schedule would allow. I’d witnessed a piece of the connection at the Flip Flop Festival in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, which celebrates those who choose a more flexible style of A.T. thru-hike — but my days volunteering in the ATC’s Harpers Ferry Visitor Center connected the dots. Every day there were new stories. I encountered so many hikers with 2,190-mile stories about “hiking their own hike” that I started to develop a complex: I would perpetually be a visitor and nothing more without those 2,190 miles.

Sometimes “why” is not the most critical question. I discovered another: “What does Trail engagement look like?” Does your answer involve boots, a beard, a pack, a 2,190-mile determination, or some combination thereof? Mine did, but only briefly. A new answer came during the week I spent on the Mid-Atlantic Trail crew. When a seasoned Trail maintainer was asked if they planned to or had ever thru-hiked, they simply acknowledged that they’d put in their miles differently.

It clicked. I didn’t have to grow a beard and dedicate, at minimum, six months of my life to the Trail. I could hike the same mile many times, and that connection would be enough.

The realities of the greater A.T. community were around me every volunteer day: the historians, the encouragers, the maintainers, the connectors, the families. All shared one constant with hikers: they had a connection, and that connection made them part of the community.

Working in experiential education, I’m really big on metaphors. Maybe “hiking your own hike” extends beyond thru versus section. I found another question to ask outside of “why”: “How can I possibly hike my own hike if I’m another barrier in my way?”

There are always barriers — some more subtle than others. When I pass others hiking, they don’t see this rich entanglement of life experience and the Trail. They don’t see time spent maintaining it, physically and intellectually. They don’t see an advisory council member. Maybe, just maybe, they see that I too love the Trail. Every time I step out onto the A.T. I have to hold onto hope that this is true, for my safety—physically and mentally.

I already carry a pack weighted by external judgments of people who merely see me as certain checkboxes. A pack that I put on simply by existing in the ways that I do. Why add the unnecessary weight of judging my “hike”?

I’m incredibly thankful for all the wonderful people who have seen beyond where they easily could have stopped. While they welcome me to this incredible community, I still can’t help but feel like a stranger sometimes.

In the end, we are all “that” kind of outdoorsy because of a shared appreciation for the Trail. That’s why I applied for the Next Gen Council. My question moving forward is how do we, as a community, start to communicate that this appreciation really is enough?

My question for you is what are you actively doing to lighten the load for everyone to hike their own hike—yourself included?