By Karen Lutz and Laurie Goodrich

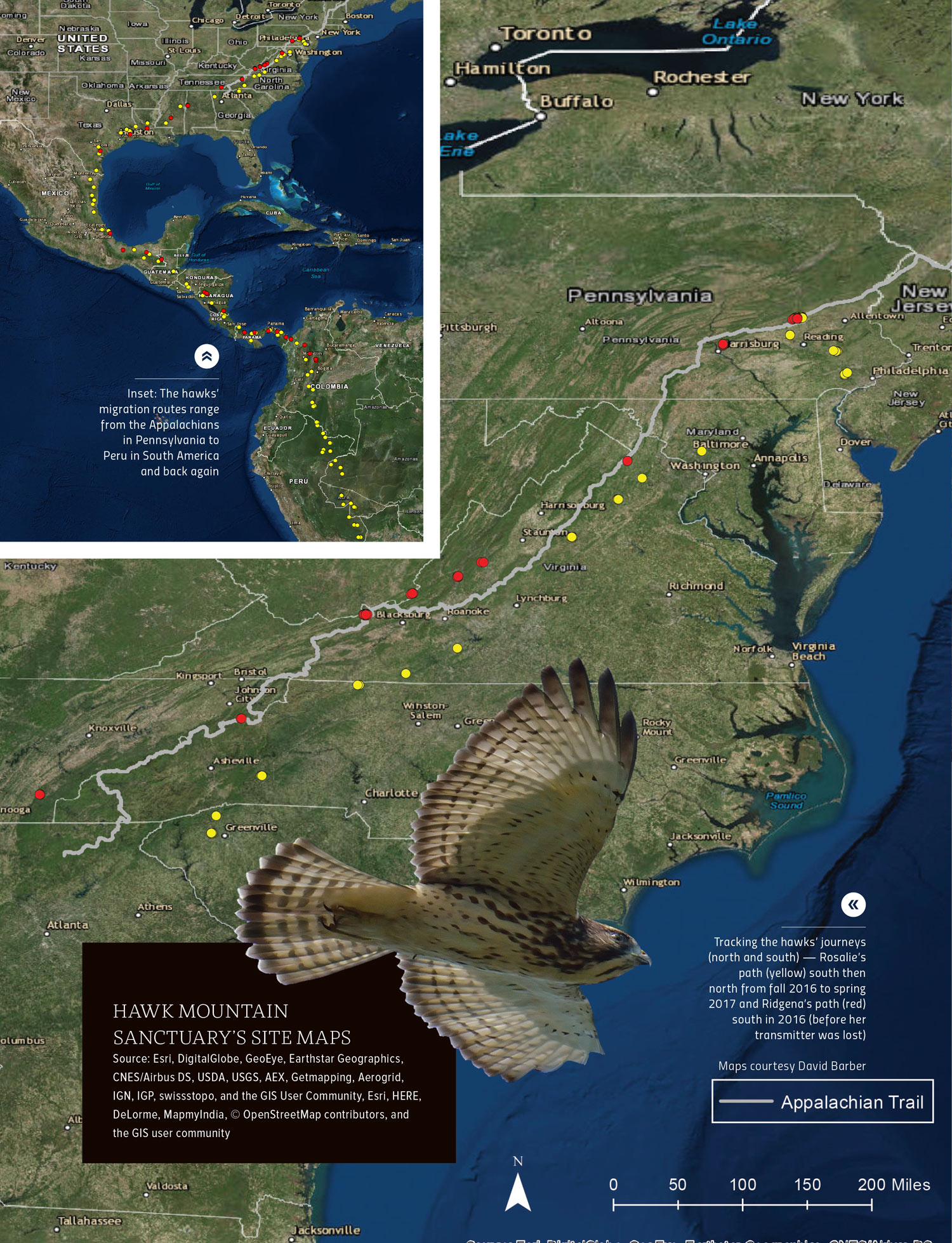

southbound thru-hikers make their way down the Appalachian Mountain chain this fall, few may be aware that their efforts are joined — and dwarfed — by a medium-size hawk weighing less than a pound. Dr. Laurie Goodrich at Pennsylvania’s Hawk Mountain Sanctuary has launched a multi-year research project that has yielded fascinating data about this species that depends on the very same large landscape that Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) and our conservation partners are diligently working to protect.

southbound thru-hikers make their way down the Appalachian Mountain chain this fall, few may be aware that their efforts are joined — and dwarfed — by a medium-size hawk weighing less than a pound. Dr. Laurie Goodrich at Pennsylvania’s Hawk Mountain Sanctuary has launched a multi-year research project that has yielded fascinating data about this species that depends on the very same large landscape that Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) and our conservation partners are diligently working to protect.

A broad-winged hawk in flight.

![]() Photo by VicBerardi

Photo by VicBerardi

Dr. Goodrich and her colleagues have pioneered research on the raptor’s spring and fall migration using tiny satellite telemetry units fitted to the birds with small unobtrusive micro-sized backpacks to collect data on the migratory habits and destinations of the broad-winged hawks. Their work has been supported by numerous sponsors including the Kittatinny Coalition, which is co-led by the ATC and Audubon Pennsylvania. And, the Pennsylvania Game Commission through the State Wildlife Grants Program.

Among these other important partners who help to protect the raptors’ migratory path (and the Trail corridor) near Hawk Mountain is the William Penn Foundation, which has been a strong funding partner with the ATC since 2015 when it was awarded a grant to build constituency for protecting sections of the A.T. in eastern Pennsylvania that are within the Delaware River Basin.

Two of the fitted birds, Rosalie and Ridgena, were sponsored by the Kittatinny Coalition and have proven themselves to be interesting characters. Rosalie was named after Rosalie Edge, a “fearless environmentalist” and the founder of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in the 1930s. Ridgena was named after the Kittatinny Ridge, which the A.T. follows from New Jersey to southern Pennsylvania. They both nested on this ridge — Rosalie nested near where the A.T. lands adjoin Hawk Mountain.

The researchers have meticulously tracked the birds as they flew parallel to the Trail along the Appalachian Range, then west to Texas, and again south through Mexico and on to their wintering grounds in South America, traveling through Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Columbia, Ecuador, finally resting in the forests of Peru — almost reaching the border of Bolivia.

Rosalie is captured at Hawk Mountain so that she can be fitted with a transmitter.

![]() Photo by Zach Bordner

Photo by Zach Bordner

The southbound fall migration for Rosalie in 2016 (where she left her nest along the A.T. in central Pennsylvania) covered 5,446 miles and is equivalent to an A.T. hiker traveling from Springer Mountain to Katahdin, flip flopping back to Springer, then flipping north again to Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania. But unlike the bipedid hikers, Rosalie covered the distance in only 157 days. She rested for a month in Parque Nacional Bahuaja Soneno in Peru. Then, this charismatic raptor left Peru on February 1, 2017 and returned to build her new nest less than a half mile from her 2016 nest alongside the A.T. where, like in 2016, she and her mate fledged two young. Following a northbound route similar to her route south, Rosalie followed the Trail that carries the famed footpath from northern Georgia. She covered 5,418 miles in a mere 83 days, arriving on April 25. Unlike her hiking companions, researchers found no evidence that ramen noodles or peanut M&Ms sustained Rosalie’s effort.

The southbound fall migration for Rosalie in 2016 (where she left her nest along the A.T. in central Pennsylvania) covered 5,446 miles and is equivalent to an A.T. hiker traveling from Springer Mountain to Katahdin, flip flopping back to Springer, then flipping north again to Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania. But unlike the bipedid hikers, Rosalie covered the distance in only 157 days. She rested for a month in Parque Nacional Bahuaja Soneno in Peru. Then, this charismatic raptor left Peru on February 1, 2017 and returned to build her new nest less than a half mile from her 2016 nest alongside the A.T. where, like in 2016, she and her mate fledged two young. Following a northbound route similar to her route south, Rosalie followed the Trail that carries the famed footpath from northern Georgia. She covered 5,418 miles in a mere 83 days, arriving on April 25. Unlike her hiking companions, researchers found no evidence that ramen noodles or peanut M&Ms sustained Rosalie’s effort.

Broad-wings nest in mixed hardwood and coniferous forests common along the A.T., typically choosing large mature trees to build their nests. While they migrate along the height of land at ridgetops, the birds tend to rest at night for short periods along the forested slopes and often will forage and feed in forest and forest edges beyond the toe of the slope. Consistent with the ATC’s strategic goal of Proactive Protection, conserving forested slopes, preventing forest fragmentation, and preserving productive farmland not only enhances the A.T. experience, but it is critically important for the long-term success of these birds and other long-distance migrants using this corridor.

For the past several years Rosalie, Ridgena, and their mates have nested close to the A.T. where it passes near the popular Hawk Mountain Sanctuary (an excellent place to visit and learn more about broad-wings and other birds of prey often observed along the A.T.) They’ve chosen large chestnut oaks, white oaks, tulip poplar, and Eastern hemlocks, ranging in diameter from a respectable 42-inch Hemlock to an impressive 67-inch white oak. These trees are relatively common in the mid-Atlantic along the protected corridor of the A.T.

Delaware Water Gap, Pennsylvania is just one section of the Trail the hawks follow as part of their impressive migratory route

![]() Photo by Raymond Salini

Photo by Raymond Salini

Broad-wings are unique in their migratory habits in that they form large clusters called “kettles.” At times, there can be hundreds and occasionally thousands of birds in a single kettle. These birds are among the first to begin migrating south for the winter, departing soon after their young have gained the ability to fly and hunt. Broad-wings begin heading south as early as late July and most have left the A.T. landscape by the end of September. Enthusiasts hoping to catch a glimpse of a kettle should find a ridgetop vista along the A.T. on a clear day with a cold front coming from a prevailing northwest wind. Aim your binoculars high in the sky and enjoy the show.

To learn more about Hawk Mountain Sanctuary visit: hawkmountain.org

To follow Rosalie on her current journey south, visit hawkmountain.org/birdtracker

Dr. Laurie Goodrich is the director of Long-term Monitoring at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary

Karen Lutz is the director of the ATC’s mid-Atlantic regional office