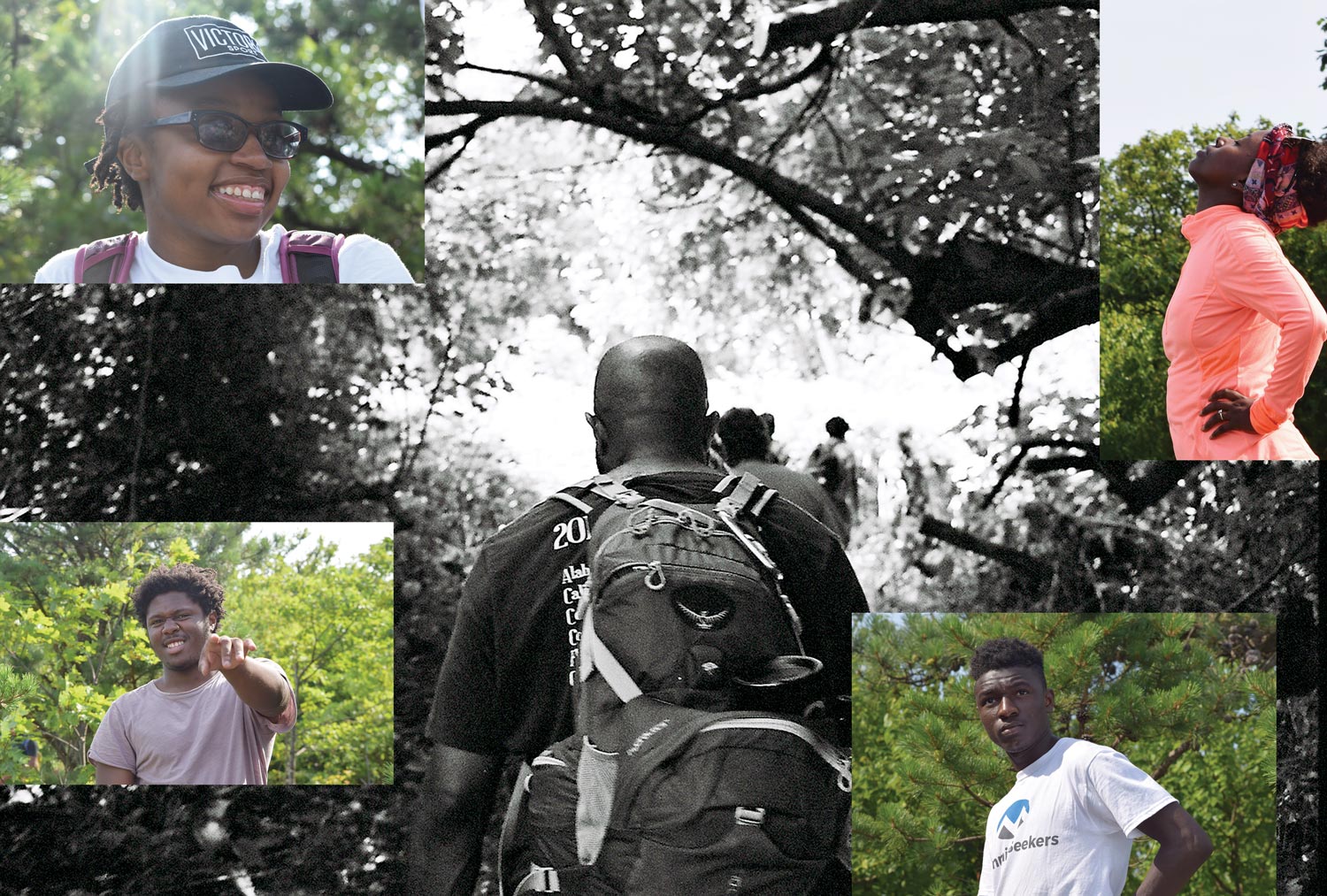

Clockwise from top right: Summit Seeker ambassador Yodit Seyoum; Outdoor Afro ambassador Victor Omoniyi; SCA ambassador Darryl Fullwood; Groundwork D.C. ambassador Ramona Davis.

![]() Photos by Julie Judkins;

Photos by Julie Judkins;

Center: The group takes a hike at the first Summit Seeker event in Anacostia

![]() photo by McKenzie Grant-Gordon;

photo by McKenzie Grant-Gordon;

People of color don’t hike, don’t scuba dive, and we don’t care about the environment. It sounds absurd to put these ill-informed myths in writing but there they were; written on flip charts and pasted on the walls as Summit Seekers tossed out ideas and stereotypes each of us had been exposed to in our lives outdoors.

Among us were people from many walks and ethnicities, Black, Hispanic, Asian, Queer…most of us identified as “other” than what might be considered the norm on the Trail, tacitly defined by whiteness, affluence, or hetero-sexuality. Are these race, class, and gender definitions relevant to a bunch of folks who just want to get outdoors? Summit Seekers found this initial ice breaker exercise one of several ways we built a shared knowledge, experience, and sense of reality.

Latino Outdoors Ambassador Siul Rivera (center) at the Harpers Ferry event

Before creating a community where “diversity” was the norm, it was as if we needed to first acknowledge some differences. The social realm experienced by people other than the usual suspects on the Appalachian Trail required that we overcome not only steep hills, rocky terrain, and other Trail challenges faced by all — but also the generally unsaid, or unspoken myths and expectations of us in the past that have typically been written by others. This was our rare chance to tell our story, our own way.

The Summit Seekers project is a collaboration between Outdoor Afro, Latino Outdoors, Groundwork USA (Groundwork Richmond and D.C.), and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC). Funded by the National Park Foundation, two Summit Seeker pilot projects, one in the San Francisco Bay area and another in the greater D.C. area, recruited multi-generational participants from many walks to both introduce them to the Appalachian Trail and/or the outdoors, hiking, and camping such that new affinity groups and cohorts might flower and begin to thrive. Participants learned practical hiking and camping skills, and got to hone those skills in the outdoors while forging teams and new Trail friendships. I attended the D.C. area project and served as an “ambassador/mentor.” This is a three-part series of summit events: an initial launch gathering at Anacostia Community Museum in Washington, D.C., an A.T. Summit weekend in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia that included an orientation from the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park superintendent, a short walk through history in the town, an overnight stay on the A.T. at Blackburn Trail Center, and a third gathering along the Anacostia River in September. The A.T. Summit included opportunities to explore African-American and U.S. history, get exposed to some of the folklore of the A.T., and get acclimated to the Trail experience. The final day of the A.T. Summit gave participants airspace to create a unique agenda for their newly formed Trail cohorts, further opportunities for Summit Seekers to share their ideas, learn from each other, and to shed some light about diversity in outdoors settings.

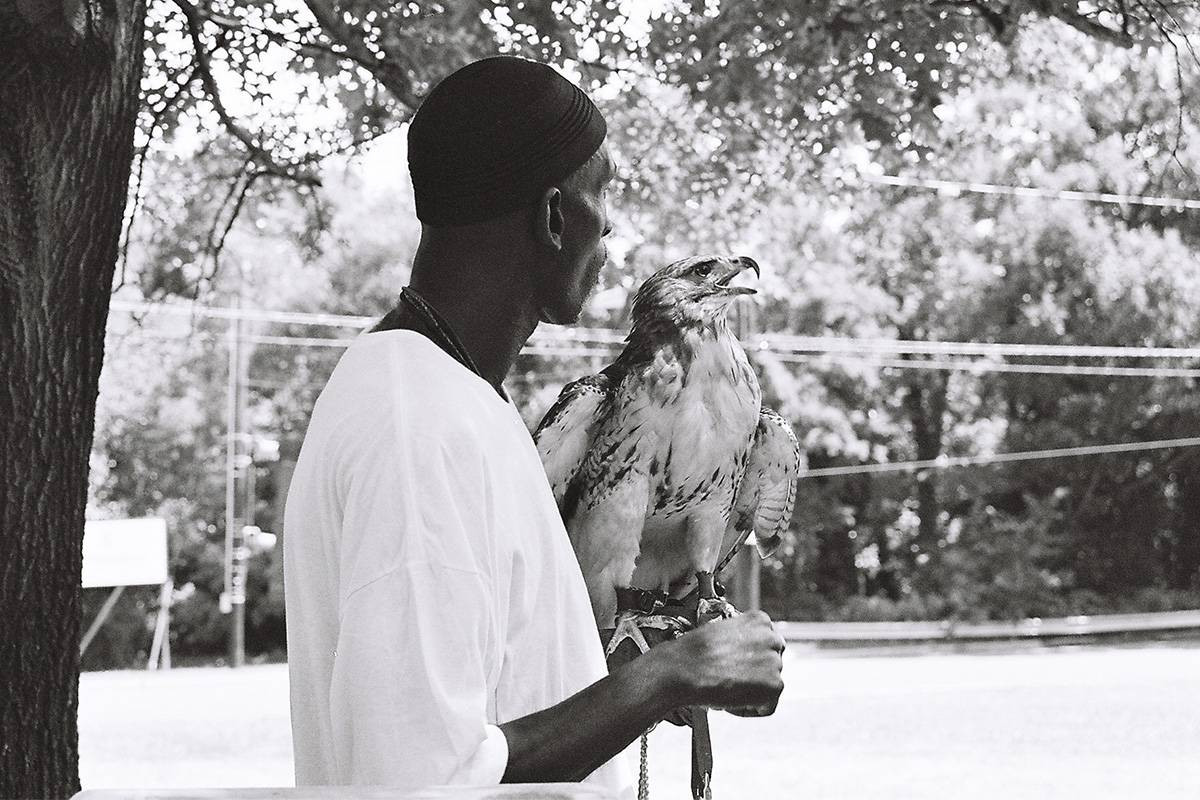

Rodney Stotts of “Rodney’s Raptors” educates Summit Seekers about birds of prey and falconry at the first event in Anacostia

![]() Photo by McKenzie Grant-Gordon

Photo by McKenzie Grant-Gordon

One Summit Seeker and ATC Next Generation Advisory Council member, Tony Richardson explains it this way: “My experience was invaluable to my personal and professional ambitions…I gained new hiking partners, mentors, memories, and life-long connections; but I would have to say the most important thing I gained was knowledge.” He continues, “The opportunity to hear directly from youth — particularly youth of color — about their connection to public lands was extremely insightful. Who better to inform strategies for diversifying the environmental movement, than the very people we are trying to engage.”

Through my lens as an African-American hiker, which includes nearly 30-plus years of section hiking and helping to maintain portions of the Appalachian Trail, I cannot say that I have ever been confronted directly with what most people would regard as racism — which usually means overt race hatred or discrimination. On the contrary, mostly I have felt that my own presence on the Trail exposed at least some of the traditional Trail folks to a genuine mystery or a quandary. Specifically, the presence of a black person doing something that many assume black people don’t do. If I felt discomfort surrounding race, which usually is around oblique discussions that attempt to unravel the mystery of why I am doing something that falls outside of usual expectations. It is sort of embarrassing actually.

Click below for the slideshow ![]()

Summit Seekers gathered for a second event in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, which included opportunities to explore African-American and U.S. history, get exposed to some of the folklore of the A.T., and get acclimated to the Trail experience.

![]() Photos by Fred Tutman and Julie Judkins

Photos by Fred Tutman and Julie Judkins

The Summit Seekers program and ambassadors challenge these expectations. Race in America is complicated and far more than simply being shades of black and white. For example, from time to time I have found myself plodding on a narrow Trail behind clumps of unknown white hikers who sometimes insist that I walk ahead of them on that Trail. I am never sure if this is because they feel safer with a big black man walking in front of them rather than behind? Is it paranoid of me to read something pejorative into this Trail behavior? For those who think that I am being paranoid or pre-judging such things I must say that an African-American in the general society, whites frequently tell me they do not see race as such and so it matters not. Yet I know from a lifetime of living as a Black person in America that people of color ignore race at our own peril. So often, for us to function in a socially appropriate way, it is incumbent for us to put whites at ease about our presence, make them feel safe, defer to their views about race, and to turn the other cheek when faced with situations that are ambiguous for us but reassuring to our white peers. It cuts both ways.

From left: Brittany Leavitt of Outdoor Afro, and an ATC Next Generation Advisory Council member, with fellow ATC Next Generation Advisory Council members Tony Richardson and Kristin Murphy at the Anacostia Park Aquatic Resources Education Center event in July.

![]() Photo by McKenzie Grant-Gordon

Photo by McKenzie Grant-Gordon

Rewind to the ATC member who assured me that he did not care what color a hiker was as long as they were willing and able to do the Trail work. It left me with the impression that his acceptance of a racially diverse club was provisional. He only recognized as legitimate people of color who could meet his standards of performance. It is sort of like being on probation, the sense that we can participate in these clubs if we measure up to standards set by others. In a way, I felt like I was again being invited to walk in front of the other hikers on the Trail until such time as I proved myself. But if I take his remarks in a more generous context, maybe he was saying he was entirely open to black people in the club if their presence enhanced the mission and goals of the club? Not an unreasonable thing I suppose, but is it a test he also applies to whites? Obviously it is not for me to say, and had I asked him to clarify I felt he would have thought me rude or a smart alec.

Click below for the slideshow ![]()

The initial Summit Seeker event was held at the Anacostia Community Museum in Washington, D.C. and included learning techniques for setting up camp and education about birds of prey and falconry by Rodney Stotts of “Rodney’s Raptors.”

![]() Photos by McKenzie Grant-Gordon

Photos by McKenzie Grant-Gordon

Rahawa Haile is female African-American hiker who identifies as “Queer.” She recently wrote about her experiences hiking on the A.T. for an article in Outside Magazine. She reports several incidents and situations during her Trail sojourn where she did not feel safe, and even felt intimidated by whites along her journey who in turn felt challenged by or distrusted her presence. I think it is hard for whites unfamiliar with the embedded culture of disparity in society to imagine how places in the wild that seem neutral, hospitable, and benign to them, might take on an entirely different connotation for black or brown hikers. The subject came up during the Summit Seekers gathering as a side note to how our Trail experiences differ at times from that of white hikers and therefore our Trail experience is sometimes at odds. As fellow Summit Seeker ambassador and ATC Next Generation Advisory Council member Kristin Murphy puts it, “I gained a new perspective on what it’s like to be anything other than a white male in the outdoors and the barriers that exist for not only getting outdoors, but feeling comfortable, safe, and welcomed in nature.”

Participants learn techniques for setting up camp at the first event in Anacostia.

![]() Photo by McKenzie Grant-Gordon

Photo by McKenzie Grant-Gordon

So the challenge of “diverse” people on the Appalachian Trail or in many other conservation clubs that have traditionally been white is a very complex journey. I cannot imagine a successful attempt at integrating or diversifying any activity without also examining and unpacking the world view, history, and values that, in many instances, have been developed to attract white donors, volunteers, boosters, and patrons. To rethink the prevailing culture of such affinity groups, then one must also consider whom they intend to serve at a fundamental level. The argument that these are public interest causes that serve everyone to some extent is a weak one if you consider that some clubs, while they do not discriminate against people of color, nonetheless, a traditionally all-white interest group has the distinct preference to serve whites. For this reason, I have come to view diversity as a very separate subject from inclusion. Diversity generally seeks to attract participation from less served constituencies in order to put aside any sense that racism is tolerated within the club or group. But inclusion is focused on exploring the structure and behavioral aspects of the group, while examining how those factors can be updated to provide an equivalent and very welcoming footing for as many different types and walks of people as possible.

CLC leads a group in a stretch circle before teaching Leave No Trace principles on an A.T. hike near Blackburn Trail Center.

![]() Photo by Julie Judkins

Photo by Julie Judkins

Where does this tent pole go? It was a question I dreaded from a Summit Seeker because, quite honestly, as a seasoned hiker/camper I am supposed to know this stuff. But quite honestly I had never seen a newfangled tent like that high-tech looking one that was brand new and just out of the packing box. In the end, we figured it out together, which spared my embarrassment. The organized chaos of people learning new skills, trying out new gear, bonding and sharing hard won knowledge was a great way to get to know new Trail buddies and bridge the various gaps of race, class, gender, and generations. These differences faded into the background as we embarked on a shared adventure together. Each one of the participants appeared to be enthusiastic about being there. All were deeply intelligent, thoughtful, and thoroughly committed to being on the Trail and determined to put forward their personal best. Each participant had a strong sense of personal worth and a deep awareness of their heritage of struggle as the descendants of immigrants, ethnic minorities, or historically disenfranchised people. To pretend that divisions of race, gender, religion, or class are not relevant on the Trail would be like pretending such things are no longer relevant in America. Obviously the newspaper headlines tell us otherwise. As an ambassador old enough to be a parent to many of them, I enjoyed sharing my skills and experiences, and I learned from them in turn.

Conservation Leadership Corps members Jen Lam and Kalen Gilliam

To me, as a volunteer, hiker, and African-American, there is something inherently democratic about a foot trail that people can use to walk from one end of our country to the other for free and to experience some of the most amazing places and spaces that have yet to be destroyed by sprawl, privatization, and industrialization. The fact that the Trail is a labor of love, maintained by countless volunteers, I feel assures that its heritage and its future remains connected to a sense of values and stewardship that would and should thrive even more with deeper representation from a wider and more diverse pool of hikers, maintainers, and advocates. The prospect of any great conservation endeavor that relies solely on one class of people to save it, would seem doomed to failure as a question of logic. Trail users and its stewards must become more diverse to both survive and become authentic in its aims. The Summit Seekers have taken these steps down an entirely new trail, one of many steps being taken toward that vision.

The September 16 event at Anacostia Park was a lovely final gathering of the Summit Seekers that included a potluck lunch, a tour of the Anacostia Resources Education Center, and a river boat adventure led by the Anacostia riverkeeper. Ambassadors and partner staff were able to close the final event with a reflection circle and discussion of next steps. Ambassadors are enthusiastic about staying in touch and seeing which summit they will seek next.

Fred Tutman is a grassroots community advocate for clean water in Maryland’s longest and deepest intrastate waterway and holds the title of Patuxent riverkeeper, an organization that he founded in 2004. He also lives and works on an active farm located near the Patuxent that has been his family’s ancestral home for nearly a century. Prior to riverkeeping, Fred spent over 25 years working as a media producer and consultant on telecommunications assignments all over the globe. Fred now teaches an adjunct course in Environmental Law and Policy at Historic St. Mary’s College of Maryland. An accomplished blacksmith, farmer, and outdoor adventurer, Fred is the recipient of numerous regional and state awards for his various environmental works. He is among the longest serving waterkeeper in the Chesapeake region and the only African-American waterkeeper in the nation.