By Amanda Wheelock

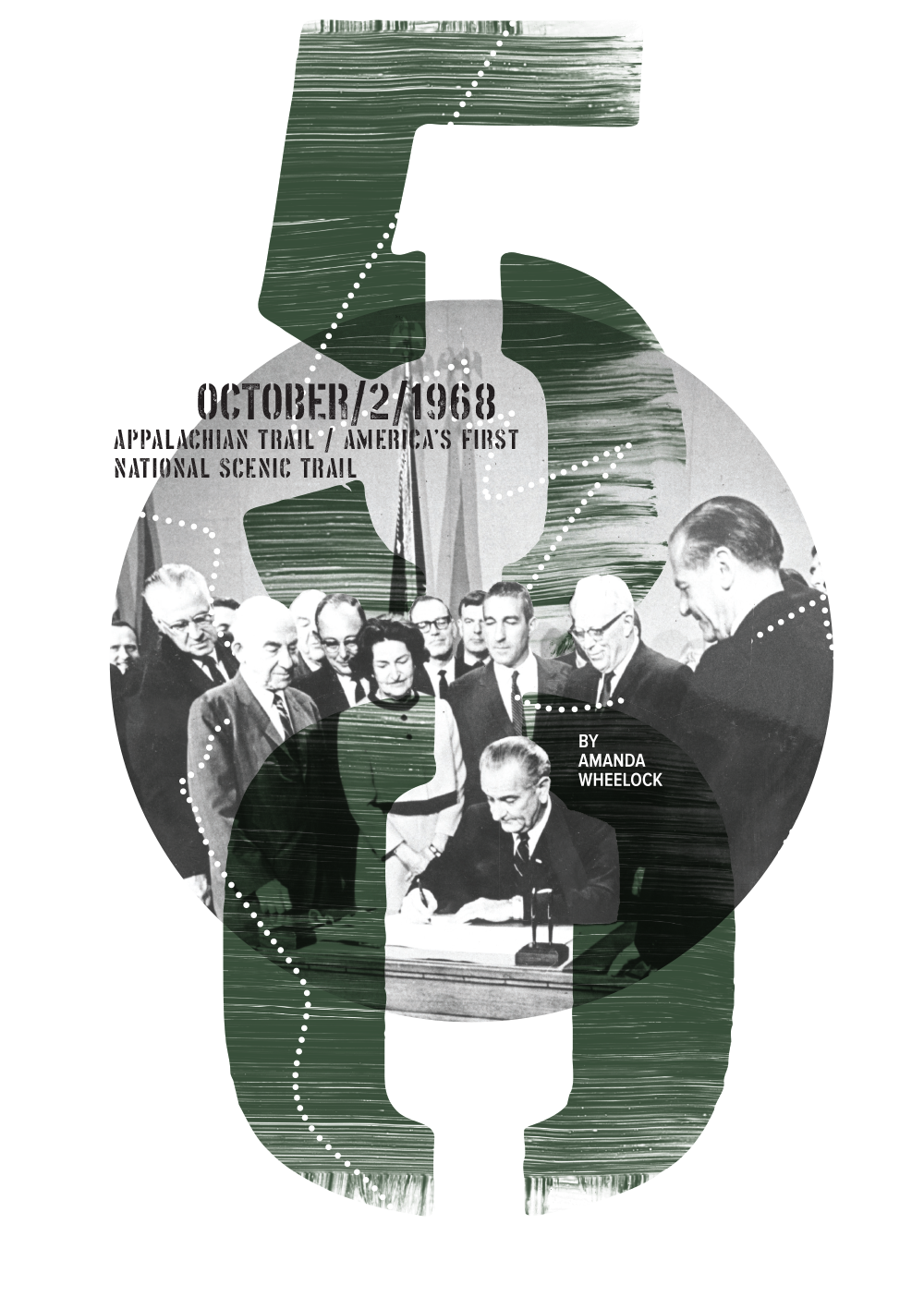

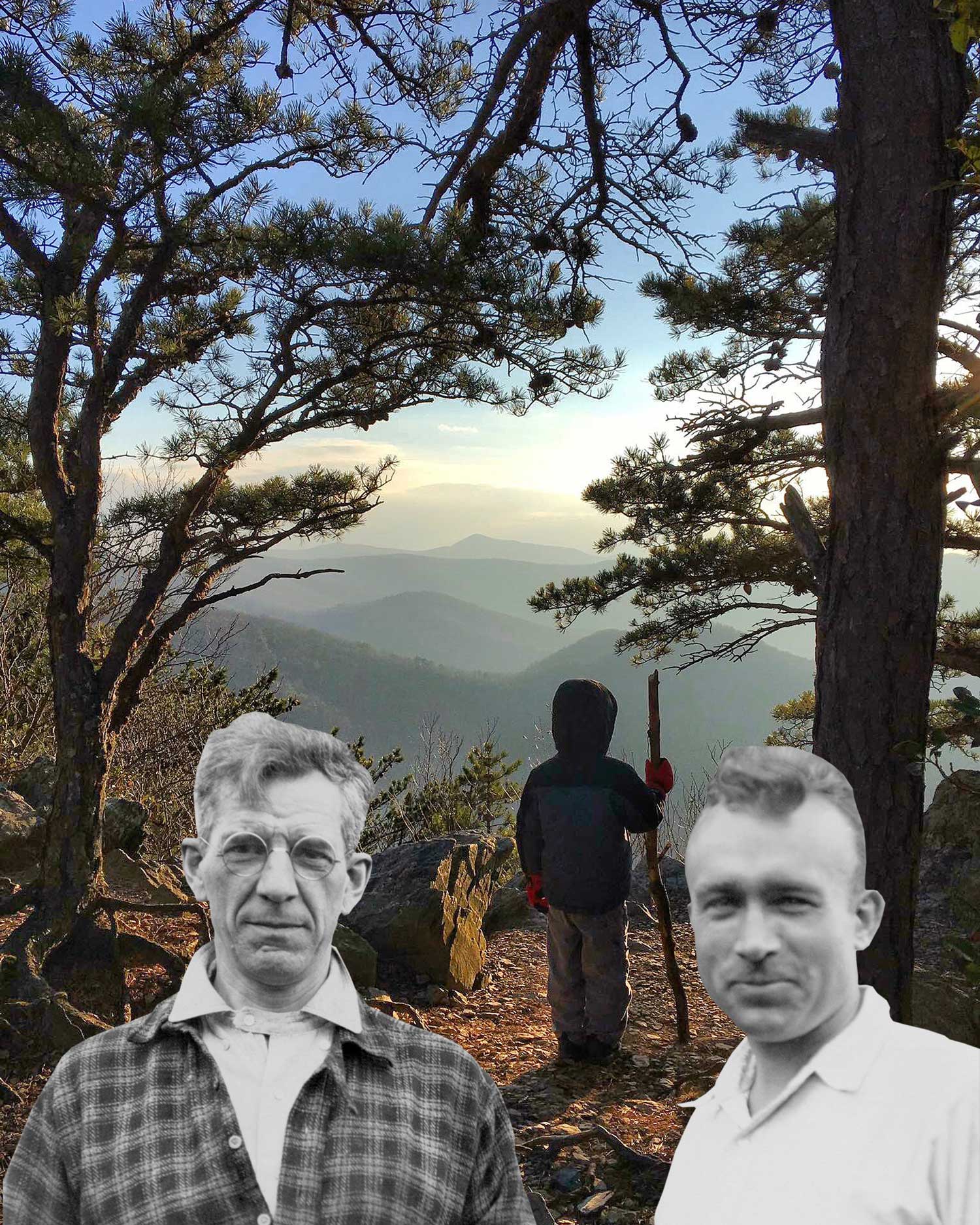

From inset: President Johnson signs the National Trails System Act in 1968 ![]() Photo by Jack Rottier; The A.T. on Max Patch in North Carolina

Photo by Jack Rottier; The A.T. on Max Patch in North Carolina ![]() Photo by Greg “Weathercarrot” Walter

Photo by Greg “Weathercarrot” Walter

October 2, 1968, the Appalachian National Scenic Trail was born. Not with the nailing of a sign or the tread of a boot, as one may have imagined, but with the stroke of a pen. On a busy day of bill signing engineered to distract or, less cynically, unite the nation during a time of anti-war protests and a hotly contested presidential election, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Trails System Act into law, officially designating the Appalachian Trail as America’s first National Scenic Trail.

Of course, the Appalachian Trail had existed on the ground for decades by this point. The Trail had been completed in 1937, just 12 years after the first meeting of what was then the Appalachian Trail Conference, and by 1968, almost 50 “end-to-enders” had hiked all 2,000 miles in one go or several. But its rebirth as the Appalachian National Scenic Trail — a trail codified in federal law as a resource of national significance — was a pivotal moment for those who loved the A.T. as well as for trail enthusiasts across the country. Passage of the National Trails System Act, wrote Benton MacKaye, was “unrivaled by any other single feat in the development of American outdoor recreation.” October 2, 1968 marked the start of a new era for the A.T., as well as the creation of a system of trails that today traverses more miles of our countryside than the entire interstate highway system.

In February 1965, President Johnson addressed a joint session of Congress (in a written “special message”) with words that ring just as true in 2018 as they did 53 years ago. “More of our people are crowding into cities and being cut off from nature…modern technology, which has added much to our lives, can also have a darker side… The air we breathe, our water, our soil, and wildlife are being blighted by the poisons and chemicals, which are the by-products of technology and industry.” To combat this blight, Johnson called upon Congress to undertake a new and creative conservation effort — one that didn’t stop at “a few more parks and playgrounds,” but rather involved the whole of the American public in protecting and restoring the country’s natural beauty. One focus of this effort, Johnson declared, would be a national system of trails developed for those who liked to walk, ride horseback, and bicycle. “We need to copy the great Appalachian Trail in all parts of America,” Johnson said, tasking the Secretary of the Interior with developing recommendations for how to implement such a system.

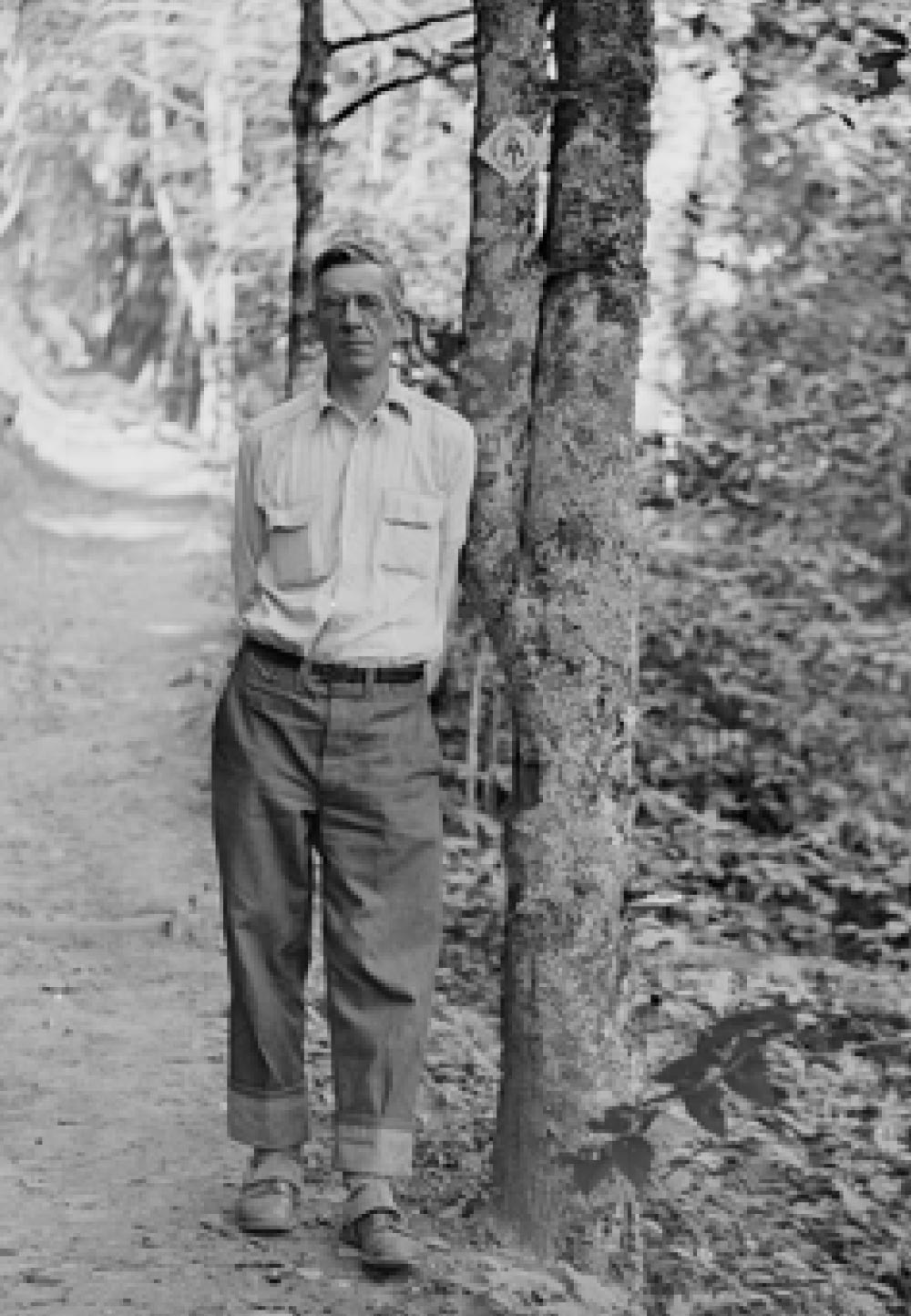

In October 1921, regional planner Benton MacKaye went public with his proposal for “An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning.” With publicity from a New York newspaper columnist (who himself blazed the first specifically A.T. section of trail), he then spent years working his network of trail and government contacts from Washington to Boston.

MacKaye and his supporters organize the Appalachian Trail Conference and present more specific plans for a hiking trail.

Toward the end of the 1920s, retired Connecticut Judge Arthur Perkins of the Appalachian Mountain Club took over the reins of the ATC from MacKaye after years of relatively little progress beyond linking existing trails and new footpaths in New York. Perkins soon drew the attention of federal admiralty lawyer Myron H. Avery and a small band of Washingtonians who had formed the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC) and started blazing the path in West Virginia and northern Virginia. Avery succeeded Perkins as head of the ATC (as well as PATC) and efforts to recruit more volunteer clubs and put the A.T. truly on the ground accelerated.

October 2, 1968 marked the start of a new era for the A.T., as well as the creation of a system of trails that today traverses more miles of our countryside than the entire interstate highway system.

It’s easy to imagine how the National Trails System could have developed without the influence of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), Trail clubs, and their dedicated volunteer leaders. With the passage of the National Trails System Act, the A.T. became a unit of the National Park System. The federal government could have easily decided to manage the Trail like any other park service unit, relying exclusively on federal staff and resources, and in essence, saying to the volunteers that had built the A.T., “thanks for your hard work — we’ll take it from here.” Our national trails could be managed like any other federal land — no ATC or Pacific Crest Trail Association needed.

But the men and women who had created the A.T. knew how integral volunteers were to the Trail. They were integral to its construction and maintenance, of course, but more importantly, the passion of those volunteers was integral to the spirit of the Trail itself, and to Johnson’s vision (as well as Lady Bird Johnson’s, who along with her staff was an unheralded driving force behind the vision, the 1965 message, and the 1968 act) for the entire national system of trails — one that involved the American people in protecting and enjoying our beautiful places.

It’s easy to imagine how the National Trails System could have developed without the influence of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), Trail clubs, and their dedicated volunteer leaders. With the passage of the National Trails System Act, the A.T. became a unit of the National Park System. The federal government could have easily decided to manage the Trail like any other park service unit, relying exclusively on federal staff and resources, and in essence, saying to the volunteers that had built the A.T., “thanks for your hard work — we’ll take it from here.” Our national trails could be managed like any other federal land — no ATC or Pacific Crest Trail Association needed.

But the men and women who had created the A.T. knew how integral volunteers were to the Trail. They were integral to its construction and maintenance, of course, but more importantly, the passion of those volunteers was integral to the spirit of the Trail itself, and to Johnson’s vision (as well as Lady Bird Johnson’s, who along with her staff was an unheralded driving force behind the vision, the 1965 message, and the 1968 act) for the entire national system of trails — one that involved the American people in protecting and enjoying our beautiful places.

So, after Johnson’s address, the ATC — still, at this point, an organization completely run by volunteers — pulled together a committee to work with the government in crafting the legislation that would create a national system of trails.

A.T. visionary Benton MacKaye on the Trail ![]() Photo courtesy ATC

Photo courtesy ATC

So, after Johnson’s address, the ATC — still, at this point, an organization completely run by volunteers — pulled together a committee to work with the government in crafting the legislation that would create a national system of trails.

Myron H. Avery is elected to the first of seven consecutive terms as the ATC’s chair.

In August 1937, the footpath was complete from Maine to Georgia, and Avery and National Park Service allies were well into a plan for overnight shelters along the 2,000-mile length of it, with some formal measure of federal protection on either side.

In 1948, young WWII veteran Earl Shaffer became the first person to hike the entire length of the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine in one continuous journey.

This committee played a pivotal role in helping Congress understand the importance of volunteers in the A.T.’s creation and management. As such, by the time the National Trails System Act was passed three years later, language was included that gave the ATC a formal seat at the table in managing the Trail. And while this formal partnership is unique to the A.T., the success of this grassroots management structure was obvious. So obvious, in fact, that it continues to underlie the management of all of our National Scenic Trails, and many of our National Historic Trails, through public-private partnerships between land managers and organizations like the Continental Divide Trail Coalition and the Florida Trail Association. Today, in an age of consistently cash-strapped federal land management agencies and a $12 billion maintenance backlog across our national parks, it is easy to be grateful for the foresight of the A.T.’s leaders, who fought for the inclusion of such non-federal partners in the management of these new national trails.

When the National Trails System Act was passed, the A.T. and the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) were designated as the first two trails in the system. At the time, the PCT was still far from complete, and over 1,000 miles of the A.T. were still located on either private lands or roads. Through the act, the federal government committed to purchasing the lands necessary to form the A.T. corridor, which meant lots of work in identifying tracts and relocating trail, and it quickly became clear that the ATC could no longer operate on volunteer power alone. Within less than a month, Lester Holmes was hired as the ATC’s first paid employee — a part-time “administrative officer” — and a year later he would become its first executive director.

“We need to copy the great Appalachian Trail in all parts of America.”

However, as sometimes happens when working with the federal government, progress was slow. Several other trails had been recommended for study when the National Trails System Act was passed, but no one seemed in any rush to examine their potential routes, let alone add them to the system. The National Park Service was slow to act on the A.T. land acquisition powers that had been authorized by the act; in fact, by 1978, none of the of the NPS lands necessary to protect the A.T. had been acquired. Once more, it was up to volunteers to lead the way. But unlike during the decades leading up to 1968, the A.T.’s volunteer leaders now had a law they could point to when working with land managers to protect the Trail. The A.T. was no longer just any old trail, but rather, one of national significance, and by 1978, momentum was in their corner.

That March, a law commonly referred to as “the A.T. bill” was passed, which essentially forced the park service into action in protecting the A.T. corridor. Later that year, another bill would create the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, stretching over 3,000 miles from Canada to Mexico along the spine of the Rocky Mountains, as well as our first four National Historic Trails — the Oregon, Mormon Pioneer, Lewis and Clark, and Iditarod National Historic Trails. The National Trails System had begun to grow in earnest.

Fast forward to 2018, and the National Trails System has grown to 11 National Scenic Trails and 19 National Historic Trails that together span over 52,000 miles across 49 states (sorry, Indiana). And those numbers don’t even begin to include the countless National Recreation Trails, rail trails, and side trails that are also part of the National Trails System, allowing a large number of Americans to enjoy national trails within just a few miles of their homes.

The National Trails System gives Americans the opportunity to experience everything from the historic Pony Express to Revolutionary battles, from the quaint New England countryside to 14,000-foot peaks. The diversity of landscapes, communities, and ecosystems showcased by our national trails is truly astounding. And as befits a system built from the ground up by volunteers, it is volunteers who have led the way in celebrating the 50th anniversary of the National Trails System Act in ways that both honor the past and celebrate the future of these trails.

A pair of leaders — Murray Stevens of New York and Stanley Murray of Tennessee — followed Avery in the 1950s and 1960s, convinced that only federal ownership of the land on which the footpath twisted could truly protect it for future generations of backpackers, hikers, and birders. Murray, becoming the ATC’s chair in 1961, shifted that talk and planning into high gear, building the ATC from 380 members to more than 10,000 while leading a small group working on federal legislation. With little-noticed direction from the office of First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, the legislation succeeded in 1968, and President Johnson signed into law the National Trails System Act 47 years after MacKaye’s original proposal was published. The A.T. became the first national scenic trail.

The National Trails System Act called for state and federal purchases of a corridor for the footpath. In preparation for much more closely working with state and federal agencies, the ATC hired its first (and for a while only) employee and moved out of Potomac Appalachian Trail Club headquarters in Washington, D.C., to the close-to-the-Trail town of Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.

Inset: A rare photo of Benton MacKaye and Myron Avery from 1931, several months after Avery was elected Chairman of the ATC; The A.T. in Shenandoah National Park ![]() Photo by Lori Nisius

Photo by Lori Nisius

The National Park Service gives the ATC responsibility for managing the Trail corridor lands.

The ATC has never had just one job as the project leader when it came to the protection, promotion, and management of the A.T. However, the accomplishment of the land-acquisition priority and the more elevated responsibilities given to it by the 1968 and 1978 acts, along with unprecedented federal and state agreements under it, called for a repositioning. Years of discussions came to fruition in July 2005 when the leadership changed the ATC’s name to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. This name change reflects the priority of preservation of the Trail corridor and its natural and cultural resources, which is essential to enhancing

the A.T. experience.

The diversity of landscapes, communities, and ecosystems showcased by our national trails is truly astounding. And, as befits a system built from the ground up by volunteers, it is volunteers who have led the way in celebrating the 50th anniversary of the National Trails System Act in ways that both honor the past and celebrate the future of these trails.

On the A.T., trail-maintaining clubs have hosted a variety of celebrations this year focused on improving the Trail. In North Carolina, the Carolina Mountain Club worked with the ATC, the U.S. Forest Service, REI, and local businesses to perform badly-needed restoration at Max Patch, a beautiful Southern Appalachian bald that sees extraordinary levels of day use due to its iconic views of the Smokies and an easy hike to the top. The A.T. Community of Fontana Dam worked with the Smoky Mountain Hiking Club, Tennessee Valley Authority, and land managers to “Kill the Dam Invasives.” And in Pawling, New York, the New York-New Jersey Trail Club worked with the local A.T. Community as well as newer A.T. partners like Groundwork Hudson Valley to perform a variety of Trail improvements.

Overall, these events and many others like them have helped raise awareness for A.T. maintaining clubs and the huge job that they have in maintaining the Trail. These events have also highlighted the value of new, diverse partnerships that will be critical to the A.T. in the decades to come as the Trail community expands and diversifies. Partners like A.T. Communities, local businesses, outdoor retailers such as REI, and other non-profits like Groundwork and the Nature Conservancy have brought new volunteers and fresh ideas to reinvigorate the A.T. as it celebrates such a milestone.

As the saying goes, “the only constant in life is change.” Trails are no exception to this rule. Each year, the A.T. is rerouted here or there, a bridge is replaced, a hillside washed out. Each walk one takes on the A.T., or any of our national trails, is different and new. Yet during this 50th anniversary of our National Trails System, I have been reminded of Benton MacKaye’s reflections on the nature of the Trail in 1971 — 50 years after he first planted such an idea into the public consciousness. “The ultimate purpose?” said MacKaye. “There are three things: to walk; to see; to see what you see.”

Fifty years isn’t a trivial milestone; for many of us, it was more than a lifetime ago that the Appalachian National Scenic Trail was signed into existence at the White House. The National Trails System has grown and changed significantly since that day, and the social and political fabrics of our nation have changed too. But it is comforting to know that the purpose for such a system, the reason why millions of people visit, enjoy, and care about these trails — really hasn’t changed much at all. Perhaps the best way to celebrate such a special year is to take a walk. See. See what you see.

For more information about the National Trails System Act visit:

trails50.org/the-trails-act

For more information about the history of the A.T. visit:

appalachiantrail.org/history

![]() Watch or listen to the podcast celebrating the 50th “Two Sister Trails — one Celebration” at:

Watch or listen to the podcast celebrating the 50th “Two Sister Trails — one Celebration” at:

appalachiantrail.org/50thPodcast

The last major stretch of Trail is acquired and permanently protected.

The ATC celebrates 90 years of protecting, preserving, and managing the Appalachian Trail.

The ATC moves into the future as the “Guardians of the Appalachian Trail”: Educating millions of visitors each year as they explore the natural and cultural wonders of the Trail; ensuring the protection of the A.T.’s surrounding lands and waters — including culturally and historically significant landscapes, threatened and endangered species, and migratory routes; emphasizing recreation-driven economies; and empowering the next generation of A.T. stewards.