FOR NEARLY A CENTURY, LEGIONS of hikers have dug their heels into the crumbling stone and weaved between granite boulders that scatter the east face of Bear Mountain en route to its summit along the Appalachian Trail. For decades, Bear Mountain has been the gateway for urban dwellers from New York City to connect with the outdoors and the famous footpath.

By Jack Igelman

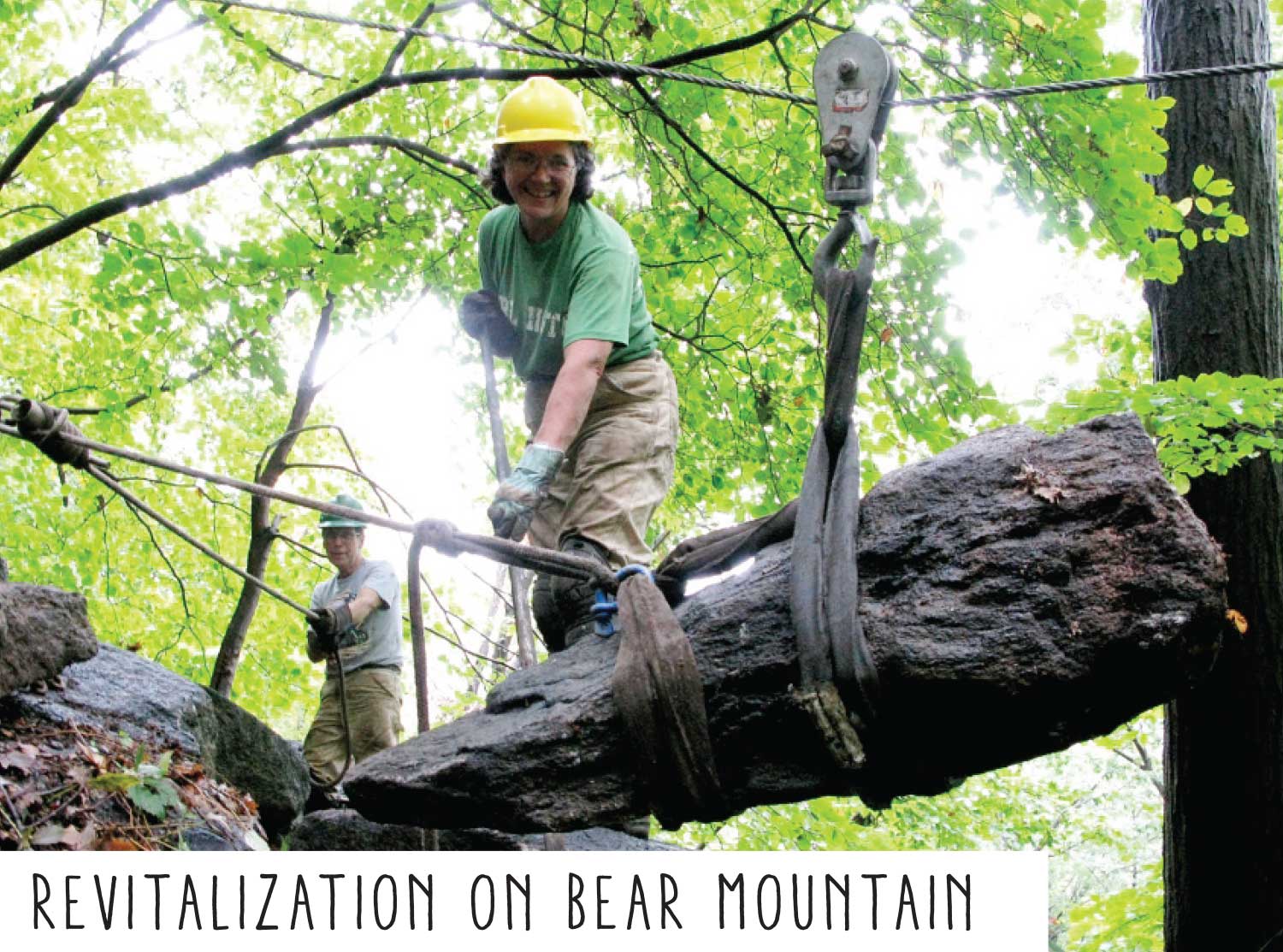

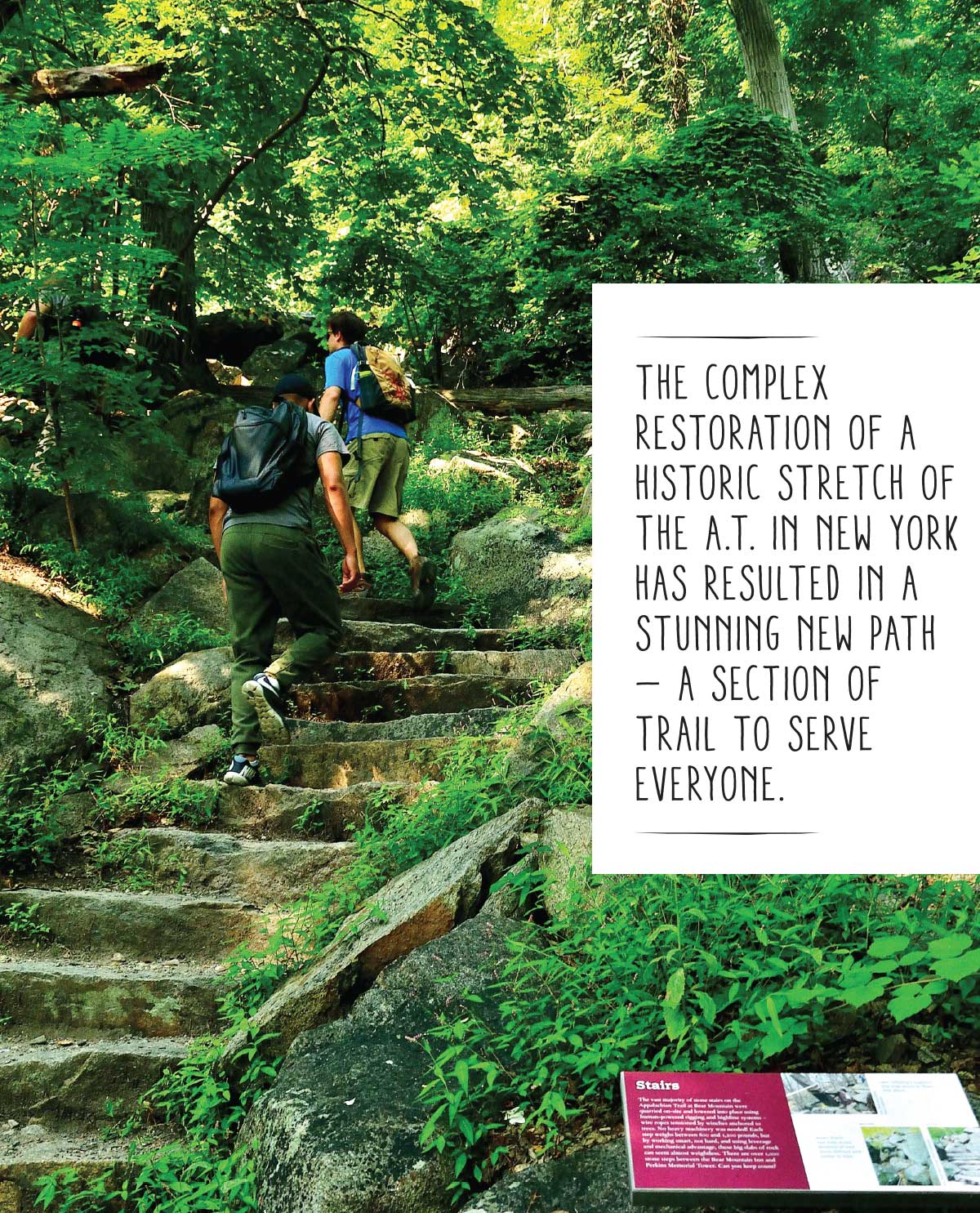

Above: ATC Mid-Atlantic Trail Crew volunteers Pat Yale and Neal Watson help guide a rock on a highline; Right: In 2016, the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference opened the “Trails for People” exhibit on the A.T. at the foot of Bear Mountain — the first interactive, on-trail exhibit in the U.S. dedicated to the art and science of trail building with displays that inform trail users about the A.T.’s origins at Bear Mountain State Park, how trails are built, and how volunteers are the lifeblood of our trail systems ![]() Photos by Christian Mena/New York-New Jersey Trail Conference

Photos by Christian Mena/New York-New Jersey Trail Conference

In fact, in 1923 this stretch of Trail became the first section of path blazed for the Appalachian Trail. Nearly 100 years later, a portion of the original 20 miles of footpath has received a stunning face lift and reroute — sustained by volunteer labor — that Trail leaders hope will last another century. “We are working on the birthplace of the Appalachian Trail,” says Ed Goodell, executive director of the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference. “That’s exciting and weighty.”

Not only is the section of Trail on Bear Mountain that cuts through two New York state parks, Harriman and Bear Mountain, meaningful to A.T. lore, but it’s among the most used — and perhaps abused — section of footpath in the entire system. In the early 2000s, when Goodell began his position, the heavily eroded section of Trail was in wretched shape. “In places it was 80 feet wide,” Goodell recalls. “We wanted to fix it. We wanted to clean it up and come up with one single trail to serve everyone. A trail to rule them all.”

Clockwise from top right: A section on the mountain’s top was made accessible to people with disabilities ![]() Photo by Jeremy Apgar; Clockwise from right: View from the eastern side of the Bear Mountain Bridge (which carries the A.T. across the Hudson River), looking north toward the Hudson Highlands

Photo by Jeremy Apgar; Clockwise from right: View from the eastern side of the Bear Mountain Bridge (which carries the A.T. across the Hudson River), looking north toward the Hudson Highlands ![]() Photo by Julian Diamond; New York-New Jersey Trail Conference’s Eddie Walsh (second from left) begins training on the project in 2006

Photo by Julian Diamond; New York-New Jersey Trail Conference’s Eddie Walsh (second from left) begins training on the project in 2006 ![]() Photo courtesy New York-New Jersey Trail Conference

Photo courtesy New York-New Jersey Trail Conference

A section on the mountain’s top was made accessible to people with disabilities ![]() Photo by Jeremy Apgar

Photo by Jeremy Apgar

View from the eastern side of the Bear Mountain Bridge (which carries the A.T. across the Hudson River), looking north toward the Hudson Highlands ![]() Photo by Julian Diamond

Photo by Julian Diamond

New York-New Jersey Trail Conference’s Eddie Walsh (second from left) begins training on the project in 2006 ![]() Photo courtesy New York-New Jersey Trail Conference

Photo courtesy New York-New Jersey Trail Conference

In 2005, work commenced on redesigning and relocating a 3.9-mile section of Trail from the back of the Bear Mountain Inn up to the top of the Mountain and down the west side to Perkins Drive, using funds from the National Park Service. More than a decade later, the final stone step was set in September 2018 by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s (ATC) mid-Atlantic regional director Karen Lutz who spearheaded the project for the organization in 2001. “Going into this, we realized it was going to be a major multi-year effort,” says Lutz. The result, she says, is one to behold. In all, visible are more than 1,300 granite stair steps (many quarried on the mountain), a section on the mountain’s top accessible to people with disabilities, and design elements and superior handiwork that harken back to the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression.

We realized this was more than a section of Trail, but the most popular destination in the region.

We realized this was more than a section of Trail, but the most popular destination in the region.

![]() We realized this was more than a section of Trail, but the most popular destination in the region.

We realized this was more than a section of Trail, but the most popular destination in the region. ![]()

The result is also a technical triumph. And while it may be an opus of trail design, ingenuity, and construction, the true hallmark of the project, maintains Lutz, is the level of cooperation between the ATC, A.T. clubs, communities, government agencies, and the scores of volunteers that united to accomplish a project of this scale. “There have been plenty of opportunities to say ‘this is enough,’” said Lutz. “The most extraordinary part of the project is that we have not lowered the bar and successfully kept an extremely high standard. This is a project we can all be proud of.”

A Permanent Fix

In 2017, 2.06-million people came to Bear Mountain State Park to picnic, ride the Merry-Go-Round, visit the zoo, or fish and swim in Hessian Lake. Many of those visitors also came to hike. For good reason, the plateau at the apex of Bear Mountain has stunning views of the Hudson River and surrounding highlands. While the top is accessible by vehicle, many choose to navigate to the top by foot.

And less than 50 miles from New York City, there’s usually a steady stream of eager walkers who typically tackle the A.T., the mountain’s only official trail on the east face, to the summit.

In the early 2000s, Trail leaders began organizing to walk the mountain and address some of the ongoing maintenance issues of the section of Appalachian Trail that crosses Bear Mountain. “We had been constantly tweaking and trying to repair this or that little piece of the trail,” recalls Lutz. “It just wasn’t sustainable.”

“In places the trail was a ditch,” says Gail Neffinger, former chair of the Orange-Rockland A.T. Management Committee during much of the planning period and first years of construction. Over the decades, he says, the trail had been relocated several times, but “it was clear then that something had to be done.” Weather and use had exposed the mountain’s granite on the mountain’s extremely steep slopes over time, crumbling into small stones that acted like ball bearings. To avoid the hazard, people would wander to the sides, creating a network of ever-widening pathways. “I can tell you this,” says Goodell. “Bear Mountain was not a place you went for a nice hike.” At the time, he suggested that the best solution for the A.T. was simply to circumnavigate the mountain. “That was not tolerated by anyone,” laughs Goodell. Still, there wasn’t an obvious route. “The real question was how do we go straight up the face and funnel all of these people on one trail. We realized this was more than a section of Trail, but the most popular destination in the region.”

In 2005, Trail leaders organized a design charrette that included a range of stakeholders and design students at Rutgers University to hash out a permanent fix. Among the decisions that grew from the gathering was the intent to hire a professional trail designer — Peter Jensen — to tackle the complexity of the project and create a trail that could withstand the forces of nature, gravity, and the impact of thousands of hikers.

In the following year, Jensen, New York-New Jersey Trail Conference’s Eddie Walsh, volunteers from the Trail Conference, and the ATC’s Mid-Atlantic Trail resources manager Bob Sickley visited the mountain often with a tape measure and 10-foot level to mark its path. In order to keep the treadway below a certain grade, the resulting design would eventually utilize more than 1,200 rocks steps. The trail would also be no less than five feet wide. “A standard 18 to 24 inch treadway just would not work,” says Sickley. “The entire design alternates back and forth between steps and stretches of flat treadway supported by crib walls.” The walls would help support sections of trail where steps weren’t possible and create a durable walking surface.

The logistics of building a trail on steep and brittle terrain that could support a hefty volume of hikers and stand-up to erosive forces was the crux. A project on this scale was beyond what had ever been attempted.

The logistics of building a trail on steep and brittle terrain that could support a hefty volume of hikers and stand-up to erosive forces was the crux. A project on this scale was beyond what had ever been attempted.

![]() The logistics of building a trail on steep and brittle terrain that could support a hefty volume of hikers and stand-up to erosive forces was the crux. A project on this scale was beyond what had ever been attempted.

The logistics of building a trail on steep and brittle terrain that could support a hefty volume of hikers and stand-up to erosive forces was the crux. A project on this scale was beyond what had ever been attempted. ![]()

Construction began in 2006 and was anticipated to last seven years. An initial $500,000 from the National Park Service seeded the project. And while fundraising remained a hurdle throughout, the logistics of building a trail on steep and brittle terrain that could support a hefty volume of hikers and stand-up to erosive forces was the crux. “A project on this scale was beyond what had ever been attempted. The technical design of the trail was a huge stretch,” says Goodell. Among the challenges was sourcing the inputs, including five-foot-wide granite steps weighing in excess of 1,000 pounds and tons of crushed stone to backfill the retaining walls.

Sickley points out that the lower part of the trail had access to an abundance of material for steps and fill that gravity had conveniently pulled to the bottom of the mountain. Trail crews would have to quarry rock onsite, split it into usable sizes, and hammer and chisel them into desired shapes, then move them into place with ropes and cables. In addition, the crews had to sledge hammer stone to manufacture their own gravel to level slopes and backfill retaining walls. “The technical stonework is pretty amazing, but you don’t realize the tons of crush and fill under the trail. It’s taken a lot of volunteer power,” says Neal Watson of Fayetteville, Pennsylvania — a volunteer who has contributed to the project since its beginning as a member of the ATC’s Mid-Atlantic Trail Crew.

Watson and his wife Pat Yale have worked a total of 25 weeks on this section of Trail since 2006. Collectively, the couples’ service on portions of the A.T. add up to more than five decades and, aside from Watson’s stint as a crew leader, each hour was unpaid. For a retired civil engineer, the Bear Mountain section of trail was a perfect match for Watson who could tackle the technical challenge of building a trail over a steep slope. “When I look at an old project from the 1800s and I see the stones, I now know what they had to go through to cut and move them,” he says. “It’s satisfying to know that several generations in the future will still see it.”

Ellie Pelletier worked alongside Yale and Watson for five seasons on the Bear Mountain project. Over the last two years she’s served as the field manager with the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference and before that, three years as an AmeriCorps service member. When she came to the project, Pelletier was a trail building novice, now she’s an expert. “I grew up loving the outdoors and this job gave me the opportunity to meet other people who love the outdoors just as much as I do,” she says. “What makes this section of the A.T. so unique is that it has been completed with the help of so many tireless volunteers and volunteer days hosted by various organizations and groups.”

From left: The New York-New Jersey Trail Conference Conservation Corps uses the A.T. on Bear Mountain as a training ground to learn trail-building techniques ![]() Photo by Jerrica Lavooy; Pat Yale, Karen Lutz, and AmeriCorp members set the final stone step during a celebration of the project’s completion this September

Photo by Jerrica Lavooy; Pat Yale, Karen Lutz, and AmeriCorp members set the final stone step during a celebration of the project’s completion this September ![]() Photo by John DeSanto

Photo by John DeSanto

The New York-New Jersey Trail Conference Conservation Corps uses the A.T. on Bear Mountain as a training ground to learn trail-building techniques ![]() Photo by Jerrica Lavooy

Photo by Jerrica Lavooy

Pat Yale, Karen Lutz, and AmeriCorp members set the final stone step during a celebration of the project’s completion this September ![]() Photo by John DeSanto

Photo by John DeSanto

Lutz explains that among the original objectives of the project was to incorporate training to raise the skill level of volunteers who could be used elsewhere on the A.T. In fact, several careers, including Pelletiers’, were launched — and professional trail building operations spawned — from working on the project. Among them, the Jolly Rovers Trail Crew Inc., which formed from a group of volunteers who assembled in 2011 and created a non-profit trail construction organization in 2014. “This project really pushed boundaries,” says Ama Koenigshof who managed the project for the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference from the fall of 2012 to the spring of 2017. “There were times it could have easily been said we could do this faster if we hire professionals, but every partner in the project stayed true to keeping volunteers highly involved in the construction process.”

The project, says Goodell, also changed lives. In fact, the project’s legacy may be measured by far more than the impact the volunteers had on the Trail, but rather the Trail’s mark on the volunteers. For Yale, the allure was being in the outdoors and building connections with other volunteers. “The Trail may be 2,190 miles, but it’s also a really long community — you see these people over and over,” she says. “You can always begin the conversation where you left off.” The coordination of so many volunteers over a decade on such a complex project has also left its mark on the ATC and its key partners, says Goodell. “It really taught us how to do trails on this scale. The whole process made us a much higher performing organization when it comes to trail building.”

The project also strengthened relationships among trail organizations and land managers that fulfills the original intent of the cooperative management system of the A.T. In all, a constellation of trail organizations and land managers were vital to its success, including the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference, the National Park Service, the Palisades Interstate Park Commission, and the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. “It was an important milestone, both for the ATC and the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference in their growth and emergence on the national scene, and for drawing together shareholders that had been siloed,” says Neffinger. “This project also helped engage the general public in a relationship with the A.T. and promoted what the Trail is about and where it comes from.”

There will be thousands of people who will enjoy this A.T. experience. For many, this will be their introduction to the Trail.

There will be thousands of people who will enjoy this A.T. experience. For many, this will be their introduction to the Trail.

![]() There will be thousands of people who will enjoy this A.T. experience. For many, this will be their introduction to the Trail.

There will be thousands of people who will enjoy this A.T. experience. For many, this will be their introduction to the Trail. ![]()

While some have criticized the trail design as deviating too far from the A.T.’s typical design model, Lutz says that the traditional design and construction wasn’t suitable given the terrain and extraordinary visitation levels. “This isn’t southwestern Virginia or western Maine; this section of Trail is different. Our goal was to build a sustainable [section of] Trail that would keep the original intent of the A.T.,” says Lutz. “I believe we’ve succeeded at that. There will be thousands of people who will enjoy this A.T. experience. For many, this will be their introduction to the Trail.”

Indeed, on any given weekend the throngs of hikers may include seasoned thru-hikers to plenty of novices from nearby urban areas — especially New York. In a sense, Lutz says, restoring the original section of the A.T. was a nod to the Trail’s philosophical roots. “What I really like about Bear Mountain is that there are probably 20 or more languages spoken on any given day,” says Goodell, who affectionately compares Bear Mountain to Times Square in NYC. “The root of the trail conference was to give people in New York and other urban areas a place to go after their labor. That was the point of the A.T. What a great way to celebrate the Trail.”