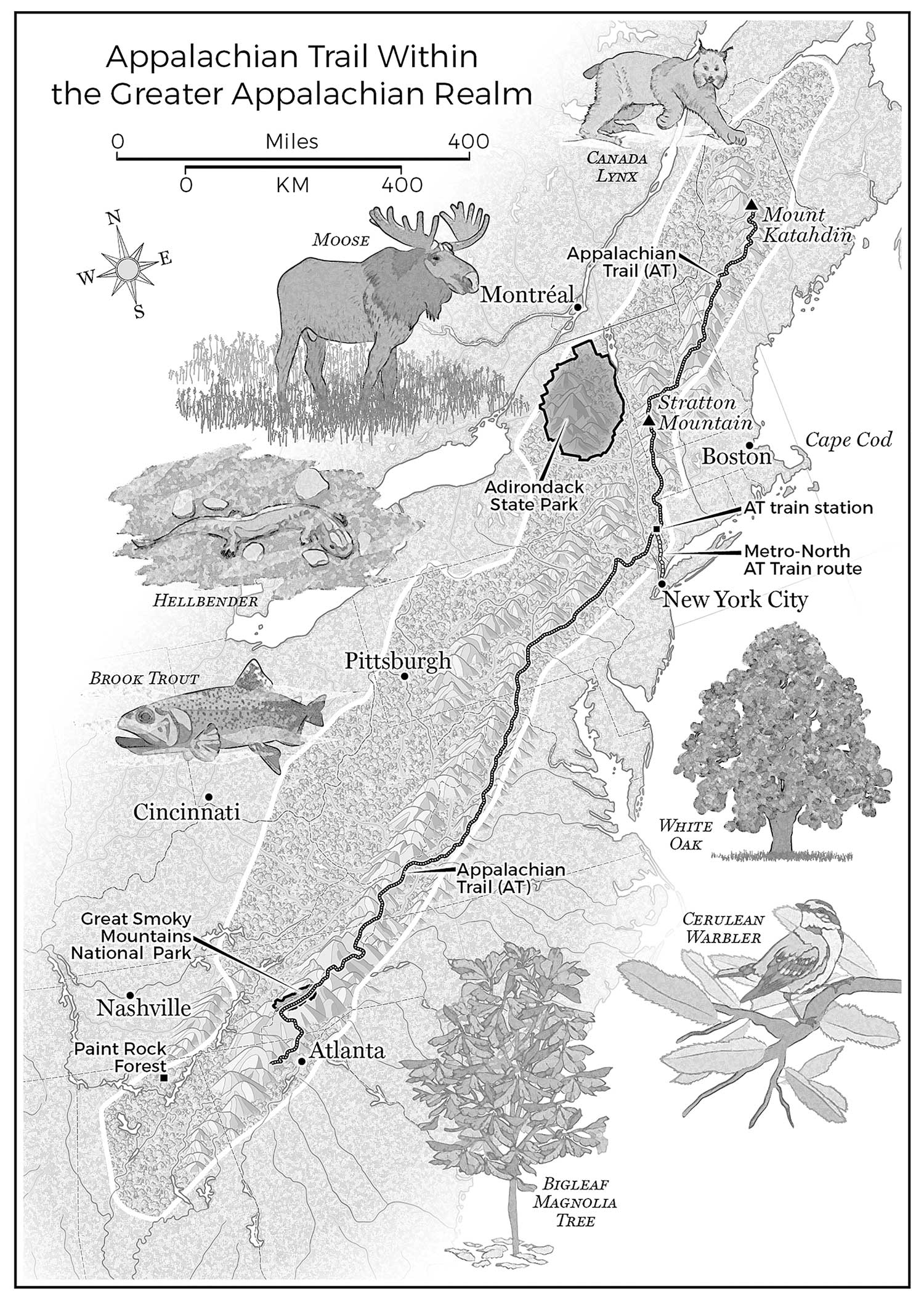

lways in the back of my mind when thinking about protecting 50 percent of Earth’s land by 2050 is Benton MacKaye — someone whose thoughts roamed far and wide as he looked around and who then reshaped the world. He had just graduated from college when, in the summer of 1900, he and a friend bushwhacked their way up Stratton Mountain, the highest peak in southern Vermont. (The story can be found in Larry Anderson’s biography, Benton MacKaye.) There were no trails to follow, and, at the summit, they shinnied up tall, swaying trees to get a better view. For MacKaye, this was an aha! moment whose echoes can still be heard.

Now, more than a century later, MacKaye’s aha! moment inspired Wild East, an initiative to protect what’s called the wide-open wildness surrounding the Trail, an area the builders of the A.T. ignored but that MacKaye championed as a realm. For the Wild Easters, it’s a landscape just as important as all the national parks in the West, and it can ignite a generation of Half Earth efforts.

At eighty-five, MacKaye could still instantly recall that July morning of swinging from the treetops. This is from a letter he wrote in 1964 to be read aloud at an Appalachian Trail Conservancy meeting:

It was a clear day, with a brisk breeze blowing. North and south sharp peaks etched the horizon. I felt as if atop the world, with a sort of “planetary feeling.” I seemed to perceive peaks far southward, hidden by old Earth’s curvature.

Would a footpath someday reach them from where I was then perched?

It wasn’t the first time MacKaye, who grew up in a small Massachusetts town, felt the land itself changing him. Several years earlier, during an August hike to the top of Mount Tremont in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, he watched the sun rise after a night of thunderstorms — “rain coming down like ‘pitchforks.’ ” He could see Maine in one direction, and, in another, “away in the distance,” he wrote to a friend, “I could make out the hills of old Massachusetts. I felt then how much I resembled in size one of the hairs on the eye tooth of a flea.” And, in his diary: “The grandest sight I ever saw was now before me, nothing but a sea of mountains and clouds.”

In 1948, Earl Shaffer, who was a radio operator in the South Pacific during World War II, became the A.T.’s first thru-hiker. Since then, more than twenty thousand people have walked the Trail end to end, and about four hundred have completed the Triple Crown of Hiking — anyone who’s thru-hiked the A.T., the Continental Divide Trail (which MacKaye helped inspire in the 1960s), and the Pacific Crest Trail, the subject of Wild, Cheryl Strayed’s memoir about a hike that helped ease her grief over the loss of her mother.

Shaffer, carrying his Army rucksack but with no tent or stove, headed north in April — “walking with spring.” He reached Katahdin in Maine 124 days later. He hiked, he said, to “walk the war out of my system.” He later thru-hiked the other way and, at seventy-nine, repeated his original south-to-north journey. The Trail, said his niece at a ceremony inducting him and MacKaye as charter members of the A.T. Museum Hall of Fame, “was a flame that started in the late forties and never died.”

“A damn fool scheme, Mac,” said the director of a summer camp where MacKaye had been a counselor, about the idea of a wilderness trail. On the other hand, MacKaye’s close friend for half a century, Lewis Mumford, the urban historian who was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and an honorary British knighthood, had a profound reaction when reading about it in 1921. “I well remember the shock of astonishment and pleasure that came over me,” he wrote.

I had a chance to meet with Mumford’s widow, Sophia, editor of many of Mumford’s thirty-eight books, when she was ninety-three. She said MacKaye had a vivid presence of his own: “He was very crotchety. While working on an idea, he was sunk deep in it and talked about practically nothing else. He came to visit us when we lived in Queens, in Sunnyside, and said he once found his way to our house by watching the stars out the taxi window. He would read you a manuscript. And not just his own manuscript. He had a philosopher brother, and he would read that one, too. He was very thin and very craggy, and rough-hewn. He wore a woodsman’s plaid shirts and always a red bandanna. He talked like an old Yankee farmer, full of ‘ain’ts,’ which was an affectation, because he was Harvard-bred. He was also so lovable, affectionate, and kind and very sweet with young people — we were younger then and considered him very old.” Then Sophie, as she was called, added, “You simply felt good with him.”

I asked her about MacKaye’s influence on conservation. Sophie thought about this a moment, and said, “He was very, very close to the soil, but there was nothing of either the homesteader or the gardener in him, nothing that drew him to raise things, or scrabble in the soil. Yet, in his own way, he was a gardener — of a much, much larger landscape.”

MacKaye’s eye was always trained on this much, much larger landscape. In his 1921 essay introducing the idea of the Trail, he asks readers to see the world with new eyes, awakening a kind of overview effect by imagining “a giant standing high on the skyline along these mountain ridges, his head just scraping the floating clouds.” Striding south through “wooded wilderness” and millions of acres of farms, the giant can see beyond the mountains to “a chain of smoky bee-hive cities” along the East Coast and to steel plants in the Midwest.

Finally the giant takes a rest in North Carolina, on Mount Mitchell, the highest point east of the Mississippi, where “he counts up on his big long fingers the opportunities” inherent in these mountains to help the people on either side by giving them “a chance to catch a breath.” This is something that awaits them in the “real open — right now, this year and next.” The task ahead, MacKaye says, will be “cutting channels leading to constructive achievement in the problem of living.”

“Some mighty big things are coming out of this trail movement in the next few years if its development grows at the pace it now shows,” said a piece in the New York Evening Post several months after the essay appeared. Over the next few years, MacKaye’s “little article,” as he called it, pulled hundreds and later thousands of people up into the hills to build sections of the Trail in their free time, an eager outpouring of effort as unexpected as the idea for the Trail itself. “A great professor once said that ‘optimism is oxygen,’” MacKaye wrote in his little article.

It’s still the case — optimism and oxygen remain undiminished.

In 1930, Myron Avery, a Maine lawyer, took on the job of completing the Appalachian Trail, and his leadership of the volunteer groups is probably why it got finished so quickly. Quoting Harold Allen, an A.T. planner and volunteer, Avery said that the Trail “beckons not merely north and south but upward to the body, mind and soul of man.” Even so, Avery wasn’t interested in MacKaye’s realm; he was pragmatic and concerned only about the Trail. “Our main problem,” he told organizers, “is to actually create it. Then we may discuss how to use it.” It’s been said of Avery, nicknamed Emperor Myronides I, that he left two trails from Maine to Georgia, one of badly bruised egos, and the other the A.T. For years, MacKaye withdrew from all work on the Trail, and his larger landscape remained neglected.

The Appalachians — MacKaye’s realm — are among the oldest mountains on Earth. They were first formed 470 million years ago, and then, 299 million years ago, in a culminating event of mountain-building, two supercontinents collided to form Pangaea, the most recent single world continent. This pushed up a wide mountain chain with ranges, plateaus, folds, and ridges. For millions of years, its tallest peaks were as high as the Himalayas.

When European settlers arrived, the idea of the Appalachians as a single place began to fracture. “The circumstances surrounding the naming of Appalachia,” wrote historian David Walls, “are as hazy as a mid-summer’s day in the Blue Ridge.”

In 1873, Will Wallace Harney, an Indianan who moved to Florida and spent much of his life writing booster pieces persuading northerners to move to Orlando, wrote a short story about Appalachia, “A Strange Land and a Peculiar People.” As David Walls notes, this was the first installment of decades of “local color” magazine stories and essays written for readers on the East Coast and in the Midwest by a succession of writers about the Appalachians and the people there, particularly those in southern Appalachia, which inescapably comes across as a place of “otherness.”

For MacKaye, the champion of the Appalachian realm, it was a place of strength and sanity, and the people most at risk of becoming stunted and benighted were the city dwellers on either side of it, the same people who now might never get to see it. Actually everyone would soon be at risk because, MacKaye wrote in his impassioned book, The New Exploration, a crisis was approaching. The realm itself might disappear or be disfigured beyond recognition.

With the coming of highways and electric power lines, cities and suburbs were explosively spreading outward like an incoming army, imposing a new kind of wilderness on the landscape — a “jungle of industrialism,” a “creeping labyrinth,” an “iron cobwebbing,” a “standardized excrescence.” Appalachia was seeing the approach of forces “far more terrible than any storms encountered within uncharted seas.” Yet the realm might still be rescued. Appalachia, MacKaye said, “is electric with a high potential — for human happiness or human misery.”

The New Exploration, which reads like a charter for the landscape, was published in 1928, seven years after the Appalachian Trail essay. It has been in and out of print ever since [most recently by ATC]. Mumford considered it a classic, writing a preface in the 1960s: “The New Exploration is a book that deserves a place on the same shelf that holds Henry Thoreau’s Walden and George Perkins Marsh’s Man and Nature; and like [Walden], it has had to wait a whole generation to acquire the readers that would appreciate it.”

“The voice of an older America, a voice with echoes not only of Thoreau, but of Davy Crockett, Audubon, and Mark Twain, addresses itself to the problem of how to use the natural and cultural resources we have at hand today without defacing the landscape, polluting the atmosphere, disrupting the complex associations of animal and plant species upon which all higher life depends, and thus in the end destroying the possibilities for further human development. That voice was needed in 1928; and because it was not listened to, it is needed even more today.”

Family photo from Ann Satterthwaite

MacKaye’s motto: “Speak softly, but carry a big map!”

Like many planners of his time, MacKaye saw humans as the beneficiaries: “The primary object of the Appalachian project is human,” he wrote in a 1922 essay. “The human biped comes first.” At the same time, The New Exploration offers a fresh calculation of what gets lost in people when landscapes disappear and what is gained when landscapes are kept intact. While earlier writers emphasized the importance of a pure wilderness above all, MacKaye saw three types of landscapes, which he called “elemental environments,” all interconnected — the primeval (wild landscapes, “the environment of life’s sources”); the rural (farms and villages); and the urban (cities).

Once people had ongoing access to all three elemental environments, a new awareness kicked in, something enduring and indelible. In his math: 1 + 1 + 1 = 4. This was, MacKaye wrote in The New Exploration, “not so much an affecting of the countryside as of ourselves who are to live in it.”

He called it “a higher estate in human development” and “the gradually awakening common mind” that would let people live as “a unit of humanity” with the next generations. This was the planetary feeling he’d had on the summit of Stratton Mountain in the summer of 1900 at the age of twenty-one, the feeling that pulled him ever forward from that day on.

Ann Satterthwaite, a Washington, D.C.–based environmental planner, has been thinking about the future of Benton MacKaye’s Appalachian realm at least since 1974, when she wrote “An Appalachian Greenway: Purposes, Prospects and Programs.” This was a proposal to fulfill MacKaye’s “wild dream,” as she put it, of protecting 28 million acres of countryside. MacKaye was still alive, although at ninety-four too frail for a visit. Satterthwaite remembers he was very excited and enthusiastic when they spoke on the phone. “It comes to me as a delightful surprise,” he wrote to her about her report, saying that from the very first moment he began thinking about the Trail, he considered a greenway “as needful to the protection of the primeval environment” as the Trail itself. “I have many times tried to make this point but not too successfully. But your brochure makes the point in no uncertain terms.”

So they never met — but to people in the Wild East initiative, dedicated to protecting sweeping vistas and landscapes beyond the Trail, Satterthwaite is the continuity, the direct line to MacKaye’s original vision, and her report is no longer an obscure, mimeographed document.

The Pawling Boardwalk over the Great Swamp – A.T. – Pawling, New York

Photo by Julian Diamond

“The Great Swamp is a twenty-mile-long wetland, and its 6,000 acres are a source of drinking water for a million people and a home for otter, beaver, mink, bobcats, and around 180 species of birds. A.T. volunteers have created the best way to see the Great Swamp, a long, gently meandering boardwalk that crosses the swamp and seems to float above it.”

– Tony Hiss

Essentially, the A.T. would be a national park wrapped up in an AONB [Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty]. Satterthwaite’s AONB idea went nowhere at the time, but her report and 1978 congressional direction stirred the federal government to start buying off-road land for the Trail, along with a permanent wild zone about a thousand feet wide.

Photo by Julian Diamond

Satterthwaite eloquently told me, “The Appalachians, historically a great divide, are the potential Central Park of the East, two thousand miles long and one hundred miles wide, which puts them on a par with the big landscapes of the West. Like Central Park, they have a lot of people on either side — in ‘beehive cities,’ as MacKaye called them. The Appalachians are the backyard of a line of eastern cities, but also the front yard of a line of midwestern cities, like Pittsburgh and Cincinnati. I didn’t get into environmental issues back then, the fact that, because of global warming, plants and animals will be making their way north through the Appalachians. But in MacKayean terms, there’s also an abiding planetary need for the mountains to reach deep into the lives of city people. Already we have to think bolder than the Wild East — bigger is always better — and include the Tamed East, the cities flanking it. Now we’re talking about pretty much all the land between the Atlantic Ocean and the Ohio River, a huge enough place. From sea to shining river.”

So far, Manhattan is the one place where the Appalachians reach deep into city life, getting as far as Grand Central Terminal in the heart of Midtown. It’s the only direct mass-transit link with the A.T., the kind of connection Ann Satterthwaite calls a “green finger.” Every weekend and on holidays, two morning trains leave Grand Central and, just about two hours and sixty-six miles later, the trains stop at a short wooden platform made of two-by-six planks that’s just long enough for a single door on a Metro-North commuter train to open up and let hikers off.

The Appalachian Trail Station, a couple miles north of the town of Pawling, New York, also has a bench and a bulletin board, both painted hunter green, and there’s a low railing, no roof, and a trash can. As soon as you get off the train, crossing the single line of track just south of the station, the Trail is right there.

Even after the A.T. wild zone was secured, there used to be worries that the section of the Trail near New York City would seem hopelessly suburbanized, serving only as a bridge or connector on the way to wilder landscapes north and south. But an eighteenth-century sense of wildness still clings to the area, and it feels immensely far away from twenty-first-century city life.

Paralleling the Oblong is the Great Swamp, another stronghold of wildness, this one 25,000 years old. It’s a twenty-mile-long wetland, and its 6,000 (mostly hidden) acres are a source of drinking water for a million people and a home for otter, beaver, mink, bobcats, and around 180 species of birds. A rare, recently discovered leopard frog species is found in the swamp, and it’s not unusual for some five thousand ducks to show up at a pond in the middle of it on a single evening.

Seventy-five A.T. volunteers have created the best way to see the Great Swamp, a long, gently meandering boardwalk that crosses the swamp and seems to float above it. Past the swamp, the trail heads up a forested hill. Down the other side is the Dover Oak, 114 feet tall, the largest oak on the A.T. A white oak like the Waverly Oaks near Boston, the Dover Oak has a twisted trunk that’s even more massive, and, ‘though at three hundred years old, it’s younger, it represents a living link to the old Oblong wildness.

Photo by Angela DeRosato

In keeping this wildness intact and nearby, the trail-makers are also ushering us into a presence older than mountaintops or continents. It’s our marvelous privilege to be participants in and guardians of an ancient community billions of years old, the continuousness of life itself.

Beyond the Dover Oak, the A.T. climbs another hill to Cat Rocks, a vista point with a panoramic view of the Oblong. It’s a preview of what Wild East wants to accomplish. Within this view is the Boniello tract, 219 acres of woods where for years a developer wanted to build fifty homes — until a fund-raising campaign made it part of the Appalachian countryside. The grand view from Cat Rocks showcases this permanently protected piece of MacKaye’s realm.

Tony Hiss is the author of fifteen books, including this year’s Rescuing the Planet, from which this essay is excerpted. As a staff writer at The New Yorker for more than thirty years, he wrote a series of classic pieces on MacKaye and the A.T. thirty years ago that were the first modern explanations of their importance to conservation nationally. He was born in Washington, D.C., and now lives in New York City.

–