Photo by Koty Sapp

isionary leaders have a rare and remarkable talent: the ability to “bring people together around a common goal and provide …a focal point for developing strategies to achieve a better future,” as organizational consultants Ron Ashkenas and Brook Manville put it.

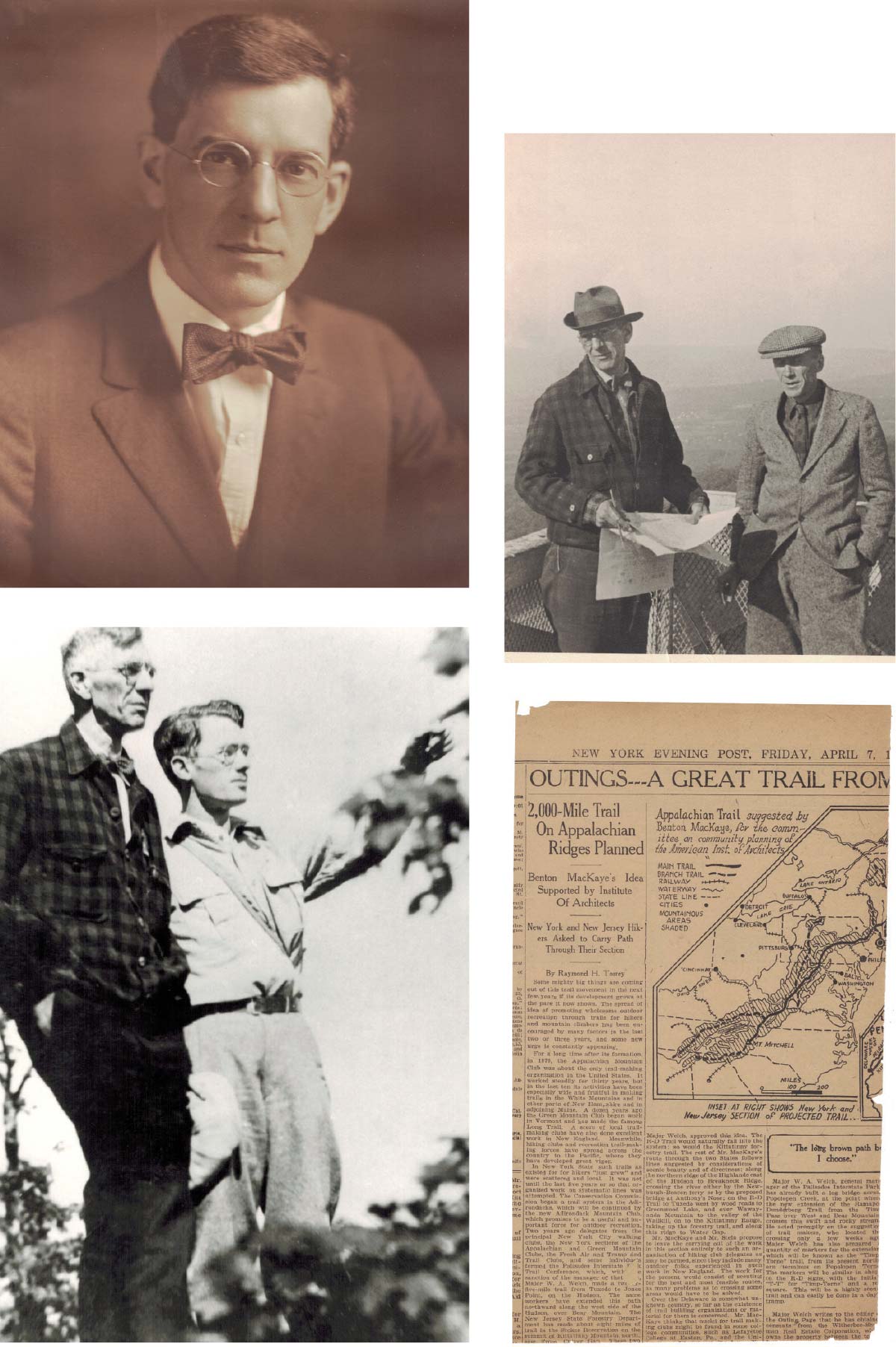

Benton MacKaye, in his October 1921 article imagining the Appalachian Trail, was able to articulate the “simple, bold, inspirational vision” Ashkenas and Manville advocate — a giant, precedent-setting plan that has motivated a strong and enduring community to achieve a common goal for what is now a century.

Our work together realizing MacKaye’s vision, however, is not yet done. Indeed, our initiative during the second century of effort to secure MacKaye’s vision is just beginning. The large landscape that surrounds the Trail, that establishes the “realm” of which MacKaye dreamed, has yet to be fully protected. Folks, roll up your sleeves!

Engaging with Giants

In his teen-aged years and as an undergraduate, graduate student, and forestry instructor at Harvard, MacKaye had the chance to consider the ideas of and walk in paths trod by giants. Born in 1879 into a family of creatives that was often in motion along the eastern seaboard from Connecticut and New York to Washington, D.C., and back to Massachusetts, he had an extraordinary perch from which he could absorb the rapid social change of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Consider these examples:

A month after his twelfth birthday in 1891, young MacKaye attended a lecture at the National Museum in Washington given by Major John Wesley Powell, the legendary Colorado River explorer. Throughout his life, MacKaye expressed great admiration for this “bearded smiling one-fisted rockwhacker;” as a “man of action and of thought,” as noted by his biographer Larry Anderson; a reformer who was passionate about geology, anthropology, and the future of American democracy.

At a low emotional point in his young life, following the death of his mercurial father and a severe stomach ailment, MacKaye in 1894 turned to Thoreau’s Walden for reflection and solace. During college, he and his brother followed Thoreau’s path into Quebec and along the Saint Lawrence, marveling at the Northern Lights and the magnificent edge of the continent, Anderson reports. Fittingly, Thoreau’s observation that “in wildness is the preservation of the world” became a rallying cry for the wilderness movement that MacKaye helped to found and the establishment of The Wilderness Society that emerged from that movement.

During MacKaye’s years as a Harvard undergraduate, from 1896 to 1900, he was exposed to philosophies of two of the great conservation pioneers of the day: John Muir and Gifford Pinchot. Muir was awarded an honorary degree from Harvard at the end of MacKaye’s freshman year; Pinchot, who was launching Yale’s forestry program, and who was closely allied with Teddy Roosevelt, lectured at Harvard in 1900 on the benefits of a career in the emerging field of forestry. Anderson documents that MacKaye’s career in forestry that followed was strongly influenced both by Pinchot’s utilitarianism and Muir’s crusades for wilderness preservation.

Nathaniel Southgate Shaler, the eminent Harvard geologist, who Anderson says was “a personal acquaintance and professional colleague of John Wesley Powell and forester Gifford Pinchot,” inspired MacKaye as professor and mentor during his undergraduate career. Richard Fisher, an instructor under Shaler’s direction, was similarly a key figure in MacKaye’s ongoing education. It was Fisher who was chosen to help start Harvard’s graduate program in forestry and who later served as the founding director of the Harvard Forest in Petersham, not far from MacKaye’s hometown of Shirley, Massachusetts. As the very first graduate, and later as a forestry instructor at Harvard, MacKaye sharpened his vision and political perspectives by absorbing the lectures and sometimes offering sharply divergent viewpoints from those two nationally significant academics.

MacKaye’s appreciation for the inspiration he was offered by his fellow students, professors, and early role models lasted throughout his long and productive career. Revisiting Harvard in 1960 for the sixtieth reunion of his undergraduate Class of 1900, he gave a short speech to his octogenarian classmates. He described how, in reviewing his observations on “geotechnics” — his studies of “how to keep [the] planet habitable, or make it more habitable” — he was able to go “to college again, at least in imagination.” He found the experience “not wholly a dream” as he reengaged with his coursework with Shaler and others, remembered hearing and later meeting Pinchot, and was able to find new inspiration from the 1960s project of his classmates to strive “for a fresh start toward a world of peace and habitability.”

Photos and clipping from the Appalachian Trail Conservancy Archives

For the first two decades of the 20th Century, MacKaye sharpened his wit as a tutor, a forestry instructor, an early employee of the United States Forest Service, and a roving political activist. Following several years of political and personal struggle and trauma during World War I and its after math, MacKaye emerged to find his own muse. Having observed and interacted with a series of intellectual and policy giants of his day, he evokes, in his most celebrated essay, a giant of his own.

The essay, of course, is MacKaye’s October 1921 article, published in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects, titled “An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning.” In the heart of the essay, MacKaye asks his readers to imagine the ability to scan the skyline from a great height:

“Let us assume the existence of a giant standing high on the skyline along these mountain ridges, his head just scraping the floating clouds. What would he see from this skyline as he strode along its length from north to south?”

The giant proceeds to inventory key stopping points along the Appalachian ridge, from “the ‘Northwoods,’ a country of pointed firs extending from the lakes and rivers of northern Maine to those of the Adirondacks” all the way to the Southern Appalachians, where our gigantic man sees Thomas Jefferson’s beloved “Natural Bridge and out across the battlefields around Appomattox. He finds himself finally in the midst of the great Carolina hardwood belt.” A sketch map included in the essay shows a proposed branch trail leading into the mountains of northern Georgia.

The giant comes to rest “on the top of Mount Mitchell, highest point east of the Rockies,” where he “counts up on his big, long fingers the opportunities which yet await development along the skyline he has passed.” These include, in short: first, “opportunities for recreation”; second, “possibilities for health and recuperation”; and third, “opportunities in the Appalachian belt for employment on the land.”

Having addressed the what and why of the Appalachian Trail concept, MacKaye asks his readers from the “skyline perspective” to consider the so-what question. What might become the longer-term impacts, on a broader social level, of building such a trail? The potential answers he offers are almost lyrical.

“First, there would be the ‘oxygen’ that makes for a sensible optimism. Two weeks spent in the real open — right now, this year and next — would be a little real living for thousands of people which the would be sure of getting before they died. They would get a little fun as they went along regardless of problems being ‘solved.’ This would not damage the problems and it would help the folk…next there would be perspective. Life for two weeks on the mountain top would show up many things about life during the other fifty weeks down below…. There would be a chance to catch a breath, to study the dynamic forces of nature and the possibilities of shifting to them the burdens now carried on the backs of men….”

“Finally, there would be new clews to constructive solutions. The organization of cooperative camping life would tend to draw people out of the cities. Coming as visitors they would be loath to return. They would become desirous of settling down in the country — to work in the open as well as play….”

With this carefully crafted essay, MacKaye offered an extraordinarily attractive set of prospects on both practical and metaphysical levels and garnered a wave of remarkably positive responses. Clarence Stein, chairman of the Committee on Community Planning at the American Institute of Architects, wrote in the introduction to a widely circulated reprint of the article: “This project…is a plan for the conservation not of things — machines and land — but of men and their love of freedom and fellowship.” No less an eminence than Gifford Pinchot, soon to be elected governor of Pennsylvania, wrote to MacKaye, according to Anderson, “I have just been over your admirable statement about an Appalachian Trail for recreation, for health and recuperation, and for employment on the land….Your giant certainly sees the truth.” And, by April 6, 1922, Raymond Torrey wrote a column in the New York Evening Post under the headline, “A Great Trail from Maine to Georgia.” He reported that “some mighty big things are coming out of this trail movement in the next few years if its development grows at the pace it now shows.” Indeed, mighty big things have, over the last century, come out of MacKaye’s historic idea.

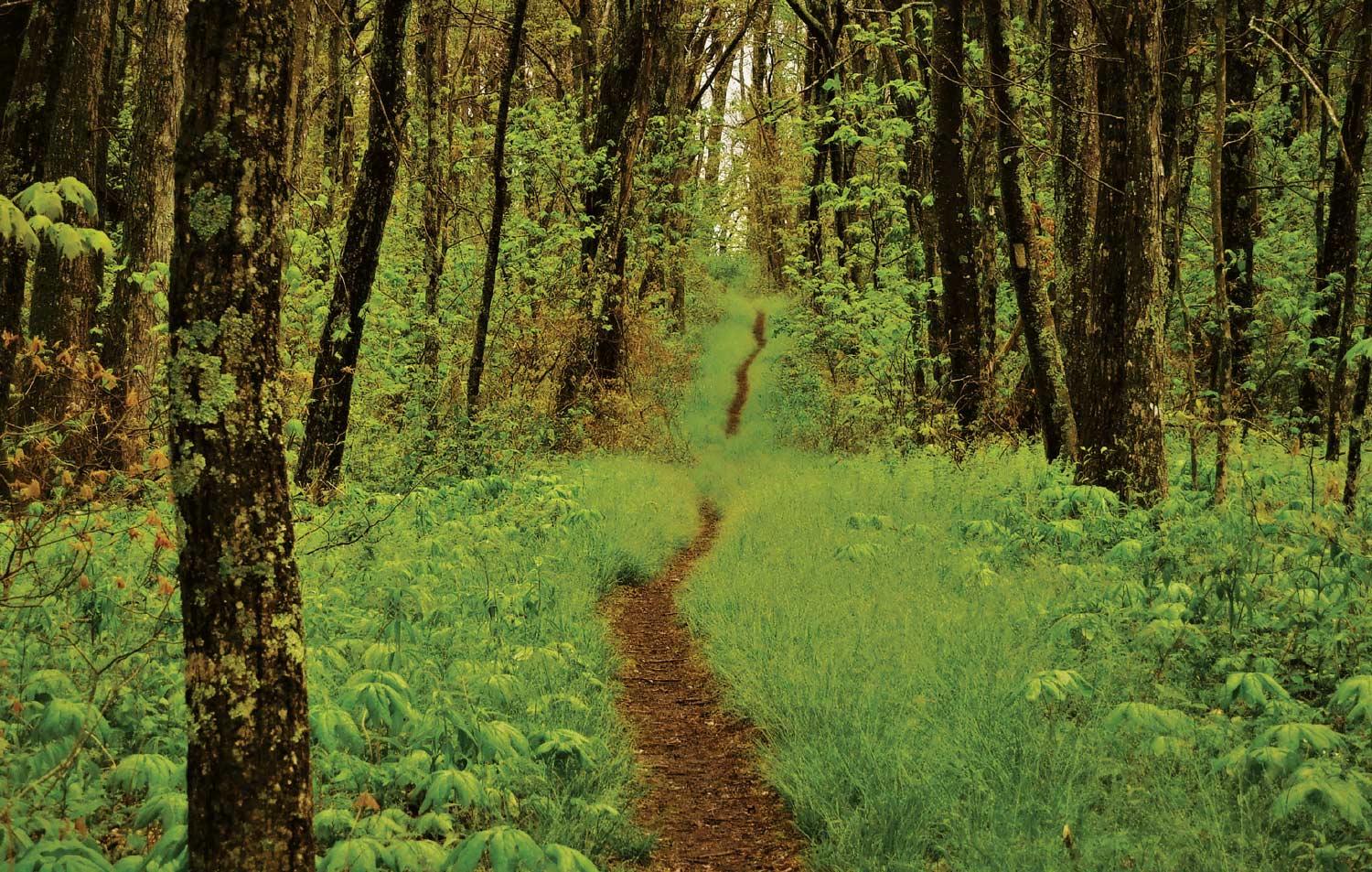

Carvers Gap – North Carolina/ Tennessee

Photo by Malcolm MacGregor

In the space of a single, concise essay, MacKaye has outlined the scope, scale, and rationale for a big, achievable project — a “landmark conservation innovation.” The term “landmark conservation innovation” used here refers to a globally important initiative characterized by five distinct attributes: novelty and creativity in conception, strategic significance, measurable effectiveness, replicability, and the ability to endure.

In addition, the A.T. is a model “large landscape initiative” in that it has been realized and continues to grow due to a multitude of partnerships that are cross-parcel (involves multiple properties and landowners), cross-sectoral (involves multiple sectors, including the public, private, nonprofit, academic, and Indigenous sectors and communities), and cross-jurisdictional (involves multiple local, district, state, and even national entities, each of which has its own laws and regulations). In the case of the Appalachian Trail, those partnerships have evolved into enduring alliances among individuals and organizations.

Consider the ways in which MacKaye’s concept has, over the past century, successfully met the criteria as a landmark conservation initiative. The concept of a continental-scale recreational trail that would link together a great many of pieces of land. Some existing trails on land owned and managed by public agencies and nonprofit organizations and some on lands held by private citizens was novel and creative in its conception. MacKaye was in 1921 thinking of conservation on a scale and scope that had not been imagined, at least in North America. The idea, further articulated by MacKaye in 1933, that the Appalachian Trail represents not only a footpath but a realm stretching across a mosaic of ownerships, sectors, and jurisdictions was, similarly, an out-of-the-box idea.

Without doubt, the Appalachian Trail has proven to be strategically significant, shaping the way that conservationists think about and plan new initiatives in the United States. To name just two sets of examples, MacKaye’s ideation became formative in the establishment of the wilderness movement in the late 1920s, the establishment by him and seven others of The Wilderness Society in 1935, as well as the Wilderness Act of 1964. Similarly, it has set the stage for the more recent emphasis on large landscape conservation, from the 2004 White House Conference on Cooperative Conservation held during the George W. Bush administration to the Obama administration’s push for the America’s Great Outdoors Initiative.

The A.T.’s measurable effectiveness can be gauged in several important ways. Consider these four:

Spatial: Completed in 1937, the Appalachian Trail now measures 2,193 miles in length. It is, according to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), the longest hiking-only footpath in the world. The ATC, the lead civic-sector partner working to educate the public, protect and maintain the Trail, and work toward its long-term, large-scale growth, today helps to protect more than 250,000 acres (about 105,000 hectares) of footpath, watershed. and landscape along the A.T.

Organizational: Key partners who work to create, maintain, sustain, and grow the Appalachian Trail include the Appalachian Trail Conservancy; the National Park Service; the U.S. Forest Service; dozens of state agencies; 31 local Trail-maintaining clubs; collaborating land trusts, advocacy, and other nonprofit organizations; and a wide array of communities that the A.T. passes through or nearby. The ATC is largely funded by its members and supporters located throughout all 50 states and in more than 15 countries.

Recreational, Cultural, and Spiritual Value: The first individual to walk 2,000 miles or more along the A.T. was Myron Avery, head of the Appalachian Trail Conference, by 1936. More than eighty years later, in 2018, more than 4,000 individuals attempted the “thru-hike,” most of them heading north from Springer Mountain, Georgia, toward Maine’s Katahdin. Less than thirty percent of them completed the entire trek. In addition, an estimated three million visitors or more made day trips or shorter backpacking visits to the A.T.

In addition to actual use, the A.T. and its siblings, the Continental Divide Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail, have considerable cultural significance in modern books and movies. Two recent indicators of the cultural significance of such journeys are the successes of the film versions of Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods: Rediscovering America on the Appalachian Trail, which grossed more than $37 million in worldwide box office sales, and of Cheryl Strayed’s Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Coast Trail, which grossed more than $52 million in worldwide box office sales, according to thenumbers.com.

The concept and practice of creating and maintaining the Appalachian Trail has been repeatedly proven to be transferable. It has been replicated along the Continental Divide Trail, which runs 3,150 miles from our border with Canada to Mexico along the Rockies, and the Pacific Crest Trail, which stretches 2,653 miles from Canada to Mexico along the Coastal Range. Additional long-distance trails have been built or are being considered from the route of the Iron Curtain that once crossed Germany to the Great Wall of China to Chilean Patagonia and beyond.

The Appalachian Trail has demonstrated an ability to endure. As a concept, it has been alive for 100 years, and, as an evolving reality on the ground, nearly that long. But, it has not yet achieved maturity as a realm or as a large landscape corridor along its length. That is the work that lies ahead.

A New Set of Challenges and a New Chance to Stand on the Shoulders of Giants

In 1675, Sir Isaac Newton, borrowing from a medieval text, wrote, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Even in 1921, MacKaye, figuratively standing on the shoulders of the likes of John Wesley Powell and Gifford Pinchot, was explicit that he saw a future in which the Appalachian Trail could be a buffer against the risks inherent in modern society. “This Trail,” he wrote, “could be made to be, in a very literal sense, a battle line against fire and flood, and even disease…against the common enemies of man.” MacKaye went further to elaborate his vision for a buffer from encroaching civilization a dozen years later, when he told a 1933 ATC conference: “A realm and not merely a trail marks the full aim of our efforts.”

Those of us alive today also strive to see a bit further. We have the benefit of an additional century of human history, as well as the knowledge that something as grand as the Appalachian Trail can, in fact, be built and beloved around the world. However, when we figuratively stand on MacKaye’s shoulders, we can also see two clearly visible trends that are profoundly troubling — the advent of global warming and the ongoing, massive loss of biodiversity. Both of these threats are existential, with the potential to change the nature of life on Earth from tropical rainforests at the equator to the icefields in the far north and south.

Facing these challenges, we appreciate that Benton MacKaye left us with a potent tool with which we can address these threats. The Appalachian Trail itself can be expanded along its entire length to serve as a large-landscape conservation area — a Wild East corridor, if you will — that can both sequester carbon to mitigate climate change and offer a durable sanctuary for a great many species now living in eastern North America.

As Abigail Weinberg, director of conservation research at the Open Space Institute, explains: “The amazing thing about the Appalachian Trail is that it’s the only way to get through the eastern [U.S.] landscape with any consistency and long-range connectivity.” In addition, the lands now protected along the Trail, and the adjacent lands that could be protected in coming years, are judged by ecosystem scientists such as Weinberg and Mark Anderson at The Nature Conservancy to have a high degree of “resiliency” — that is, “the capacity of a site to maintain its biological diversity, productivity, and ecological function, even as the climate changes.” In short, if we are able to protect a wide swath of land around the A.T. footpath, we can not only add to the scenic and recreational value of the Trail, but we also can make the Trail an invaluable tool to serve as a carbon sink and a sanctuary of last resort for myriad species.

Photo by Thomas Spiltoir

My guess is that the delegates will be heartened when they hear the remarkable story of Benton MacKaye and his giant dream coming true, now celebrating its 100th birthday. I imagine that MacKaye would be highly gratified, wherever he now resides, when he perceives that substantial new acreage is being added to the global total of protected lands, thanks to the efforts of the Appalachian Trail community. And, I am quite confident that our great-great grandchildren will raise a glass in honor of the efforts we will now undertake to guard the vibrancy of life on Earth, as they celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Appalachian Trail idea a century from now.

Jim Levitt is a cofounder and director of the International Land Conservation Network (ILCN) at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He also serves as a fellow at the Harvard Forest, Harvard University, and a senior fellow at the Highstead Foundation. A graduate of Yale College and the Yale School of Management, Levitt has edited four books, penned numerous articles, and offered presentations on innovation in the field of conservation, both historic and present-day, in venues as diverse as Boston, Brussels, and Beijing.

–