Where It All Began

How an estate in northwestern New Jersey with ties to the settlement house movement became the birthplace of the Appalachian Trail.

Sometimes

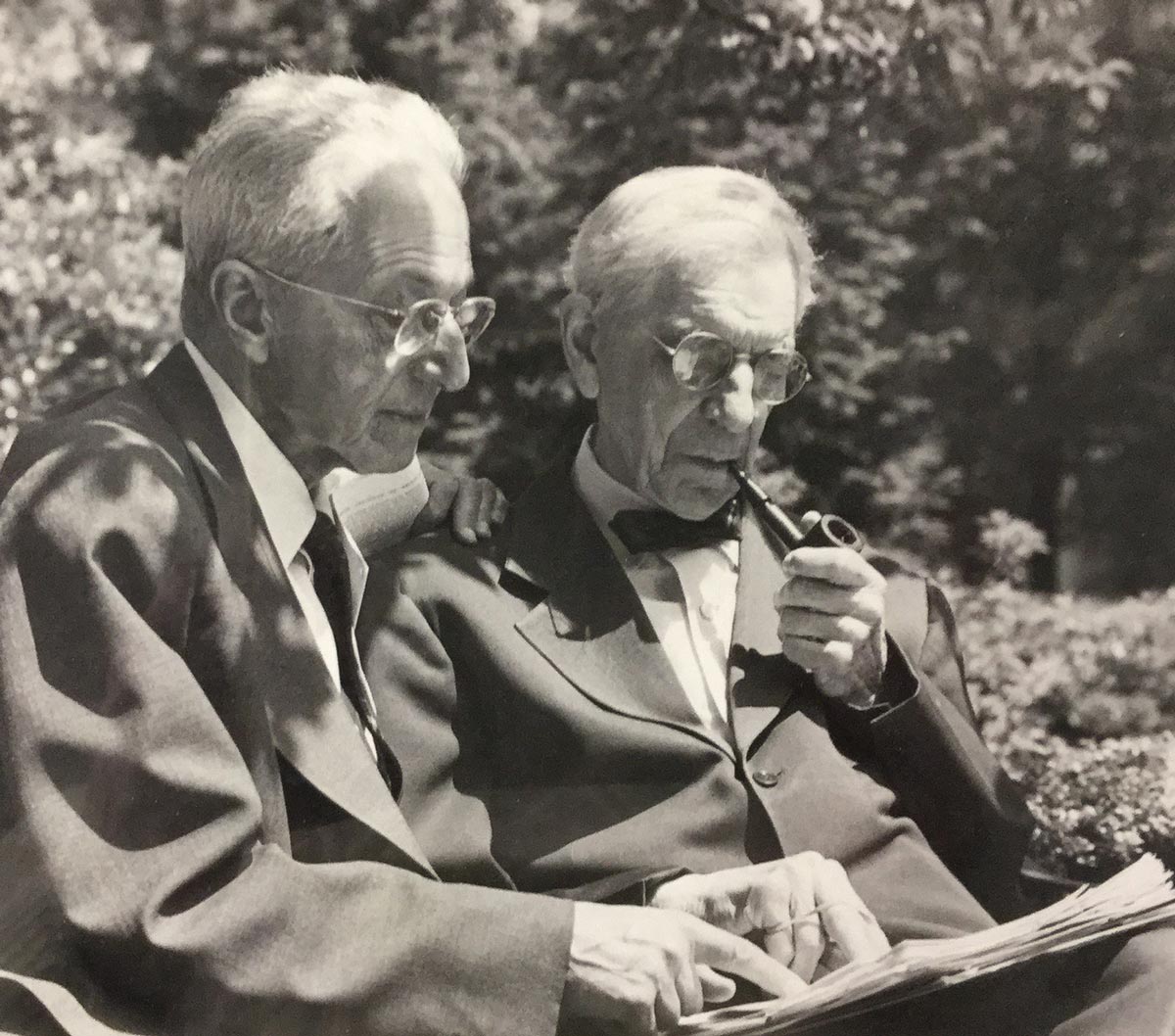

For Benton MacKaye, the visionary founder of the Appalachian Trail, it was a visit to northern New Jersey in the summer of 1921 that changed the course of his life. That summer, MacKaye was grieving his wife, Betty, who had died from suicide in New York City in April. A friend invited him to come stay with him at a small farm he had recently purchased near Mt. Olive, New Jersey. That friend was Charles Harris Whitaker, an architect and editor of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).

MacKaye had already begun musing about a trail from Maine to Georgia through the Appalachian Mountains. He later said he first came up with the idea on a hike up Stratton Mountain in Vermont in July 1900. But it was while staying with Whitaker, far from the noise and distractions of city life, and at his friends’ urging, that he put pen to paper and started sketching out his ideas in writing.

In the late 1890s, Dr. John Lovejoy Elliott established Hudson Guild, a settlement house in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan. In recent years, the neighborhood had seen an influx of immigrant families from Ireland, Italy, Germany, and Greece, as well as African Americans who were fleeing the South. The new arrivals found jobs in the shipyards and factories along the Hudson River and lived in poorly built tenement buildings or rooming houses nearby. The increase in population density and poor sanitary conditions soon heightened underlying problems of disease, hunger, and crime.

Elliott had met Jane Addams, the founder of Hull-House in Chicago, a few years before and was deeply moved by what settlement houses were striving to accomplish. In Chelsea, he organized a social and recreation club for young men, which was quickly followed by clubs and programs for other groups including children and working women. “Our fundamental purpose is to help people help each other and themselves,” Elliott said about the primary aim of these programs.

In the following years, Hudson Guild established the first free kindergarten in New York City and offered vocational training, athletic programs, healthcare services, and summer outings to nearby parks and campgrounds. Some 20 years after its founding, the guild bought a property in northern New Jersey to enable city children to learn about farming and enjoy traditional camp activities. The goal was not to make “farmers out of city folks,” Elliott later clarified, in an interview with the New York Times, but to enable people to “learn about how things grow and about other mysterious things that happen in the country, concerning which city people know so little.”

It is undoubtedly Hudson Guild Farm’s reputation as a place for airing and debating big ideas that prompted Charles Whitaker to choose it as the backdrop for the meeting he facilitated with Benton MacKaye and Clarence Stein about the former’s ideas about a recreation project involving an Appalachian Trail. Stein had designed some buildings on the farm and so was already familiar with the location.

On Sunday, July 10, 1921, the three men met — in the “room where it happened,” to quote Lin-Manuel Miranda’s lyrics from Hamilton — and emerged after Whitaker agreed to publish an article by MacKaye in the AIA journal, and Stein agreed to help promote the idea through his professional circles.

The significance of the meeting is hard to overstate. MacKaye’s biographer, Larry Anderson, wrote in his 2002 book that the July 1921 meeting “launched the Appalachian Trail.” MacKaye himself, reflecting on the meeting some 50 years later, wrote to the ATC chairman at the time, Stanley Murray, “On that July Sunday half a century ago, the seed of our Trail was planted. Except for the two men named, it would never have come to pass.”

The tradition of social welfare is alive and well at Hudson Farm Club and its associated foundation. Twice a year, the club organizes a hike on its grounds for over a thousand residents of nearby communities to enjoy the scenic beauty and wildlife sightings.

The hikes typically raise from $50,000 to $150,000 — depending on the turnout (and the weather) — but the donations are only part of the point. “The greatest reward is the community coming together and working towards a common goal of completing the hike,” said Sharon Leon, the volunteer organizer of the fall hikes on the Byram township side of the grounds.

One can only imagine that Dr. John Lovejoy Elliott, who established Hudson Guild as part of his lifelong experiment in “neighborliness,” would approve.

And so it happened that a brief sojourn in New Jersey — a mere couple of months in a lifetime that lasted 96 years — changed the course of MacKaye’s life. Just as the Trail that he envisioned has had a transformative effect on the lives of all who spend even only a few hours appreciating its many wonders.