National Park, Virginia

Photo by Raymond Salani III

fter being ushered into the local office of an Atlanta-based member of Congress, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s (ATC) southern regional director Morgan Sommerville and a Georgia Appalachian Trail Club volunteer were seated at his desk. On display was a meter. Its swiftly spinning digits flickered in a blur. “That,” boasted the fiscally conservative congressman while pointing at the gadget, “is the national debt.”

fter being ushered into the local office of an Atlanta-based member of Congress, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s (ATC) southern regional director Morgan Sommerville and a Georgia Appalachian Trail Club volunteer were seated at his desk. On display was a meter. Its swiftly spinning digits flickered in a blur. “That,” boasted the fiscally conservative congressman while pointing at the gadget, “is the national debt.”

Not exactly words you want to hear when your pitch is to steer funds from the U.S. Treasury to protect the Appalachian Trail. For the next quarter of an hour, Sommerville and the volunteer politely listened to a lecture on government overreach. When his commentary concluded, the congressman looked at them and proclaimed that, despite the escalating value on his meter, he would pledge his support because, of course, everyone loves the Trail.

Sommerville has met with hundreds of lawmakers from across the ideological spectrum and, like this meeting, they often end well. The evidence is not only the decades-long bipartisan support of the footpath, but the thousands of acres of protected land that buffers the Trail, creating one of the most unique and iconic national parks in the U.S. And, don’t forget the creation of the National Trails System Act of 1968 that has now protected trails in every state of our Union. That systematic level of protection and support for the Trail wasn’t inevitable. Rather, it’s the product of decades of work of staff and volunteers persuading people in power that the Appalachian Trail matters.

Among them is Sommerville. When he began his tenure at the ATC in 1983 as the only employee in the southern regional office, his job description included land planning, volunteer training, and duties that directly involved the maintenance and protection of the Trail. Eventually, Sommerville was encouraged to meet with local congressional delegations.

“It was new to us as regional employees,” he says. “I was a one-person office, so we were generalists; we did everything to make it work.” At the time, recalls Sommerville, the visits to congressional offices included updates on current projects with volunteers from local clubs. Soon enough, the visits focused on supporting efforts to protect and acquire tracts of land to protect the Trail experience and its original vision to connect the human spirit with nature.

Sarah Mittlefehldt, author of Tangled Roots: The Appalachian Trail and American Environmental Politics, says that MacKaye was poetic in describing his vision for the Trail. “He often used the metaphor that the head and brain of the project are technocratic government experts, but the heart and soul are the citizens of all stripes building it,” she says. “He really presaged that eventually there would be a connection between the federal government and a decentralized grassroots initiative.” According to Mittlefehldt, MacKaye’s biggest impact on policy was through his writing and public speaking and his connection with federal agency leaders to leverage support for the Trail.

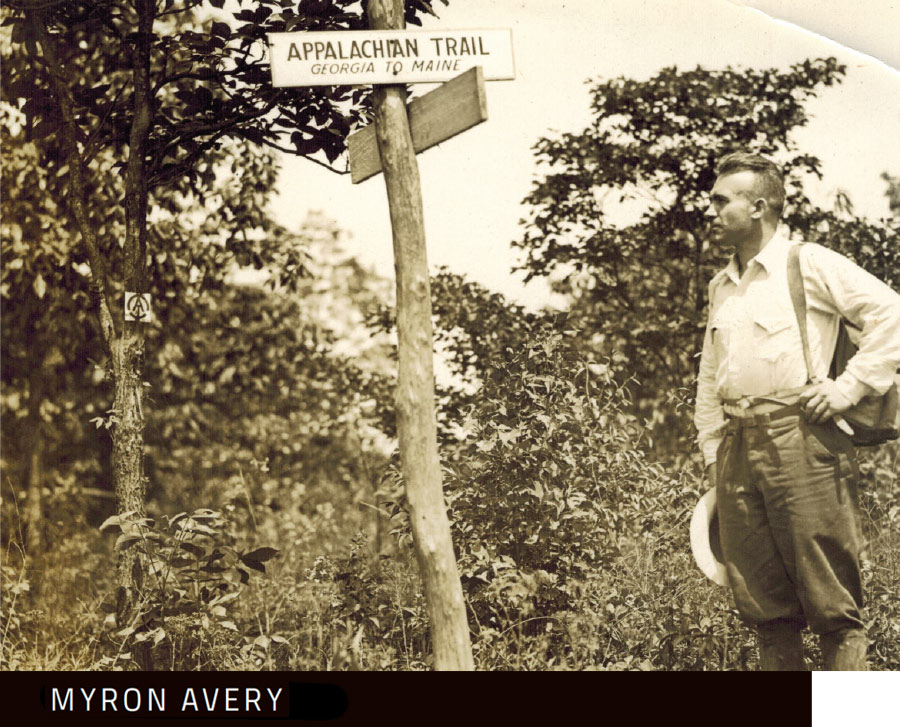

Though MacKaye was criticized for neglecting details, it was the first ATC chairman Myron Avery’s strategic thinking, says King, who sharpened the A.T. vision and played a vital role in completing the Trail in 1937 by focusing its mission on the footpath and its corridor. As the first president and cofounder of the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC) in 1927, he served as ATC chair from 1931 to 1952 and developed meaningful relationships with the U.S. Forest Service and the National Park Service. In addition, Avery campaigned for the Trailway Agreement of 1938, which gave the Trail official status among the federal network of public lands and was one precursor to the National Trails System Act of 1968.

Daniel Hoch was among the first to propose a national trail system in 1945 as an amendment to a highway aid act. The one-term representative from Pennsylvania — an avid hiker, Trail-club president, and ATC board member — proposed an amendment calling for an authorized “national system of foot trails” that would have provided $50,000 annually for land acquisition. Avery testified at the hearing and argued that the A.T. was a national project, “rather than 14 separate projects, which might have 14 different and varying policies.” It failed, along with another similar bill in 1948 that Hoch had a friend introduce, but cemented the idea of the Trail as a federal public good.

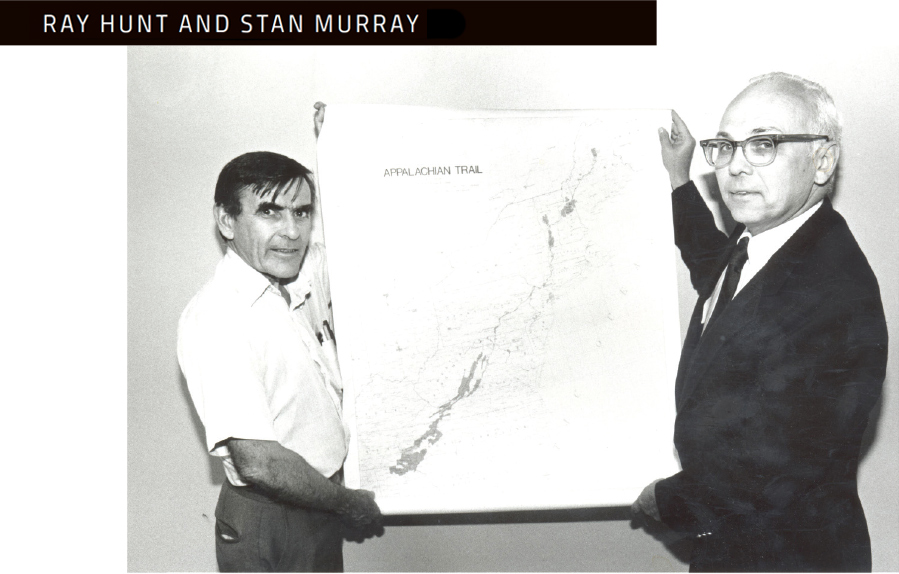

King said that, while not much happened in the 1950s, support for federal involvement in conservation whipped up in the 1960s. Stan Murray became the ATC’s chair in 1961 and focused on expanding the organization’s membership from a few hundred to thousands to demonstrate that there was political justification to back the Trail. The organization also became more savvy in its lobbying and public relations efforts. Following a day of hiking in Maine in the late summer of 1963, Murray formulated an effort to garner federal support for the Trail and commissioned the PATC to spearhead a lobbying campaign in D.C. since Murray lived in Tennessee. A committee was formed and chaired by Walter Boardman of the Nature Conservancy and supported by volunteers of the PATC, including Ed Garvey and Jean Stephenson, who lived within striking distance of congressional offices. According to a forthcoming history of putting the Trail in place, by Tom Johnson, the legislation might not have succeeded without Murray’s “troops on the ground” in Washington, who visited congressional offices, attended hearings, and presented facts about how the Trail would benefit elected officials’ constituents. “They were educated, dogged, and concerned citizens,” says King. “They were skilled at knowing what they were talking about and presented the information in a way that resonated.”

Their timing was right. The lawmakers they met in 1964 were members of the “Conservation Congress” that passed landmark rules to protect the environment, such as the Wilderness Act and Clean Air Act. Murray’s committee drafted legislation in 1964 that established the A.T. as a federal interest. In 1965, hearings were held about their proposal in September that focused on ATC-led testimony from volunteers. Over the next few years, several bills to create a national scenic trail system were introduced. Thanks to help from Lady Bird Johnson, who convinced her husband’s administration to embrace it enthusiastically, Republican Representative Roy Taylor of North Carolina’s 1967 bill eventually made its way to President Johnson’s desk, where he signed, on October 2, 1968, the National Trails System Act into law, 47 years after MacKaye’s original proposal for the Trail was published. The act designated the A.T. and the Pacific Crest Trail as the first national scenic trails. While the Pacific Crest Trail was mostly on public land (but not fully blazed), only one-third of the A.T. was on public land.

There’s no doubt that the 1968 act was monumental, but King says that the act’s 1978 amendment — known as the Appalachian Trail bill — was more consequential. Driven by ATC discontent with the pace of land purchases to protect the corridor, its membership activated to light a fire under Congress and its public agencies. Members testified at hearings and committees on Capitol Hill, and wrote hundreds of letters to lawmakers. In March 1978, President Carter signed the bill directing the National Park Service to proactively buy lands and provided a budget to do it. “It would not have happened without the congressional pressure to get it done,” says King. “There wouldn’t be much of a corridor without it.” Not only that, it cemented the ATC as a leader in the national trails and conservation movement.

Among the slices of tracts conserved through the LWCF is Rocky Fork in Tennessee that was acquired over a seven-year period and completed in 2015 with the support of several legislators, including Tennessee Senators Lamar Alexander and Bob Corker (retired), Representative David Price of North Carolina, and Representative Phil Roe of Tennessee. Price, a member of the A.T. Caucus (whose bipartisan mission is to unite members of the U.S. House of Representatives in working together to sustain and protect the Trail), grew up in the Appalachian Trail Community of Erwin, Tennessee, not far from the iconic balds of the Roan Highlands. (The caucus was cofounded by A.T. enthusiasts, Representatives Don Beyer of Virginia and Phil Roe of Tennessee and previously included new White House chief of staff Mark Meadows.)

Sunbeams after a storm in Rocky Fork State Park, Tennessee

Photo by Jerry Greer

A.T. – Roan Mountain, Tennessee/ North Carolina – courtesy of the Northeast Tennessee Tourism Association

So, it’s not surprising that Democratic Representative Price shares a tight connection with Senator Alexander, a Republican who also loves the Trail. The two legislators have been champions for the A.T. in their decades-long attention to the ATC’s advocacy in D.C. Together, the pair helped secure the funds to purchase a precious 10,000-acre tract of land on the Tennessee-North Carolina border that is a crucial enhancement of the A.T. treadway and viewshed, and allowed a four-mile relocation of the Trail to a much-improved route. Two-thousand-and-seventy-six acres now make up Lamar Alexander Rocky Fork State Park 10 miles from Erwin; the rest was added to Cherokee National Forest. Price believes that its protection was because of a strong partnership among a range of organizations with both sides of Congress. “The A.T. is a unique resource for the nation and one that isn’t going to be automatically protected,” says Price. “No matter how much you love the Trail, sometimes you have to organize to protect it to make sure the resource is secure.”

While Price and Alexander are easy to convince of the value of the A.T. and why it should be protected — like such others as Senators Patrick Leahy of Vermont, Richard Burr of North Carolina, and Tim Kaine of Virginia (an A.T. hiker for decades) — some lawmakers are not so easily swayed. That’s why the ATC has for nearly two decades participated in the annual “Hike the Hill” in February, when national scenic trail advocates from across the nation converge on Washington and knock on congressional doors to continually remind them why they should support the A.T. and other trails around the country. The ATC’s goal in the nation’s capitol as well as back home in the states is to broaden and deepen relationships with more potential federal champions as well as craft stronger coalitions to protect the Trail.

And while Sommerville and other ATC staff have become pros at educating legislators of the A.T.’s value, they’re not in D.C. That’s the reason the ATC has established an advocacy office in D.C. “We have been doing this since day one. It was a radical act of advocacy to get this trail done,” says the ATC’s director of federal policy and legislation, Brendan Mysliwiec. “We created this system. We wrote this act. But we have to be physically present to send our message. Our relevance depends on us being here.”

What the A.T. community has had in droves for years, Mysliwiec points out, is “everyday activism,” whether that’s repairing stairs on the treadway or speaking with local officials. His job, he explains, is to “be loud, proud, and clear and concise in our messaging to make sure that every inch of the Trail and surrounding landscape is protected for all and forever.” After all, no one volunteer has the time to visit multiple congressional offices, federal agencies, and partner organizations. His job is to make sure that federal decision-makers are aware of the Trail’s needs and that meeting them also helps meet other community needs within their states and districts. He’s continuing a decades-long tradition of synthesizing the Trail’s grassroots engagement and activism — fueled by volunteerism — into professional advocacy for broad federal policy.

Currently, Mysliwiec is working on congressional appropriations, including getting a much-needed boost for the A.T. National Park office; promoting the importance of public participation and the necessity of state involvement in federal decision-making via the Clean Water Act and National Environmental Policy Act; and securing passage of the Great American Outdoors Act, addressing critical deferred maintenance needs and permanently releasing the congressionally-authorized level of money from the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

King points out that having boots on the ground in the capitol helps the leadership of the ATC focus on other vital tasks, such as maintaining sound finances or implementing landscape conservation projects. It also continues a long tradition between the ATC and the federal government, which he says, have “always been joined at the hip.” The ATC will continue to pave the way for the vast network of volunteers that have been the bedrock of the Appalachian Trail for decades and to ensure a forceful and tenacious voice for the future.