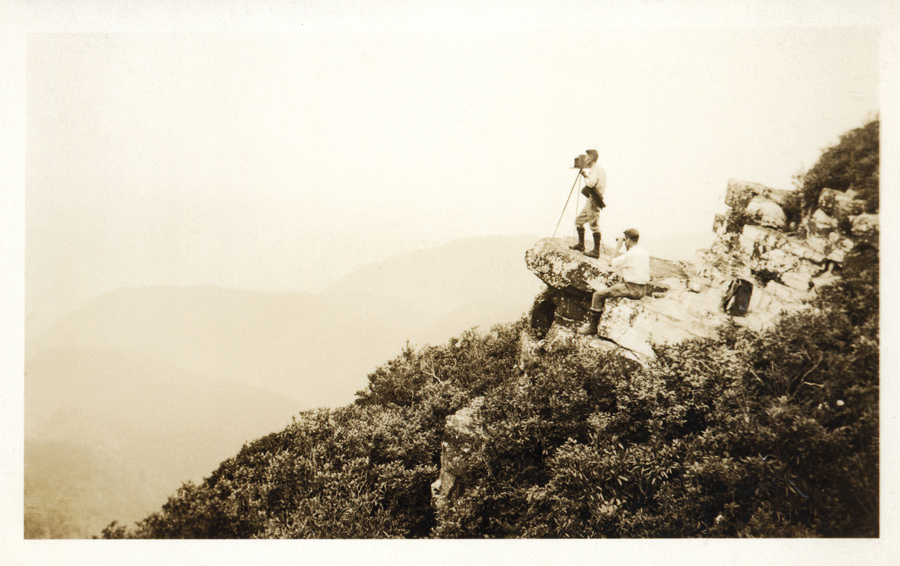

The View from Charlies Bunion (formerly called Fodderstack) on the A.T. — Smokies. While cataloging peaks, and the distance between them, Masa was careful to use the names given to them by the local settlers and the local Cherokee Tribes.

Courtesy of the Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, North Carolina

Legacy

With little to no compensation, he dedicated the last eighteen years of his life to turning his passion for photography into a legacy of environmental conservation. Yet while he strove to preserve the mountains he adored, few of his photographs have survived. Only about one thousand of his images are accounted for, including perhaps four dozen in the Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s (ATC) archives, and an estimated 2,500 negatives are lost — with his essential work of the Smokies assumed to be among the missing work. The bulk of his negatives were purchased after his death by another Asheville photographer, Elliot Lyman Fisher, but those vanished when Fisher died in 1968. Yet, while the photographs were lost, the legacy of his work persists today.

From left: Masa and Horace Kephart on Graybeard Mountain; Masa’s handwritten notes on his photo of the Roan Highlands; Myron Avery and Masa during one of Avery’s trips to meet with North Carolina/Tennessee hiking groups.

Photos courtesy of the ATC Archives

From top: Masa and Horace Kephart on Graybeard Mountain; Masa’s handwritten notes on his photo of the Roan Highlands; Myron Avery and Masa during one of Avery’s trips to meet with North Carolina/Tennessee hiking groups.

Photos courtesy of the ATC Archives

In addition to his camera, Masa hiked with a measuring wheel not unlike Avery’s and sent him meticulous notes, map notations, and prints of ranges with the peaks written in—all in the process of selecting the best route for the fledging A.T. through North Carolina, into Tennessee, and even to Mount Oglethorpe, which was not yet selected as the southern terminus. Those heated routing discussions (more accurately, arguments) went on for years among three or four factions, and Masa and Kephart were keys to their resolution. Kephart had a seat on the ATC’s board from 1929 until he died, and then Masa briefly had that seat until he died (the only person of color on the board in its first 80 years). Both men are now in the A.T. Museum Hall of Fame.

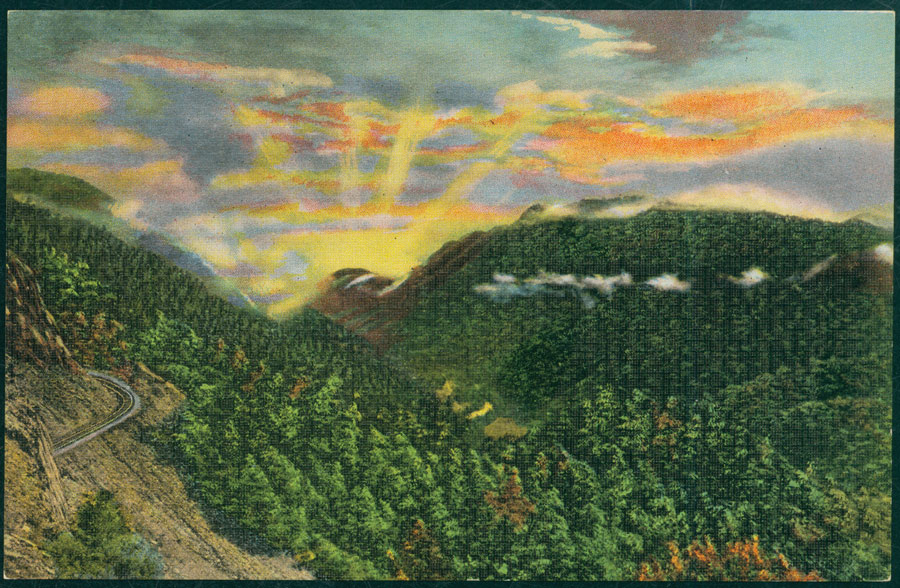

Clockwise from left: Nantahala Gorge at sunrise; A postcard created from Masa’s Nantahala Gorge image; Masa with his fellow Carolina Mountain Club members

Photos Courtesy of the Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, North Carolina

Top to Bottom: Nantahala Gorge at sunrise; A postcard created from Masa’s Nantahala Gorge image; Masa with his fellow Carolina Mountain Club members

Photos Courtesy of the Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, North Carolina

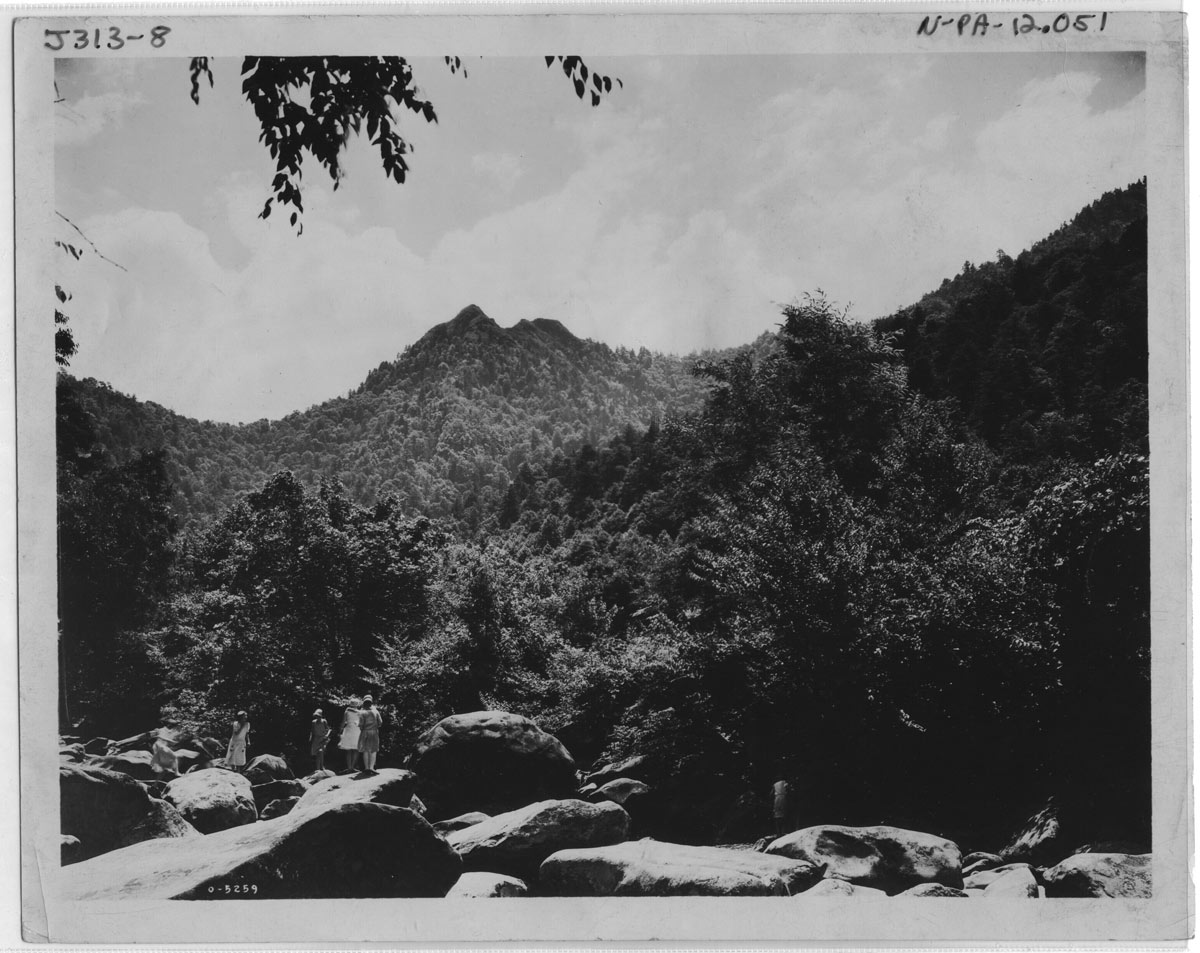

Masa’s legacy lives on in the park he helped create. His images and studies helped to beautifully present this special place to the eyes of many who had not seen it for themselves and bring the importance of its protection to the forefront. In addition to his photography, Masa would carry his measuring wheel (a homemade bicycle wheel odometer) and take meticulous notes on everything he saw along the way for those who officially named landmarks. For example, he and Kephart are credited with naming Charlies Bunion, a friendly jab at another hiking companion. The range through the park today is known for its plant and animal diversity and its importance goes far beyond its ridgetops. It supports a large number of endemic species, including 100 native species of trees and 1,500 types of flowering plants (more flowers than any other national park), making it one of the most important natural areas east of the Mississippi River.

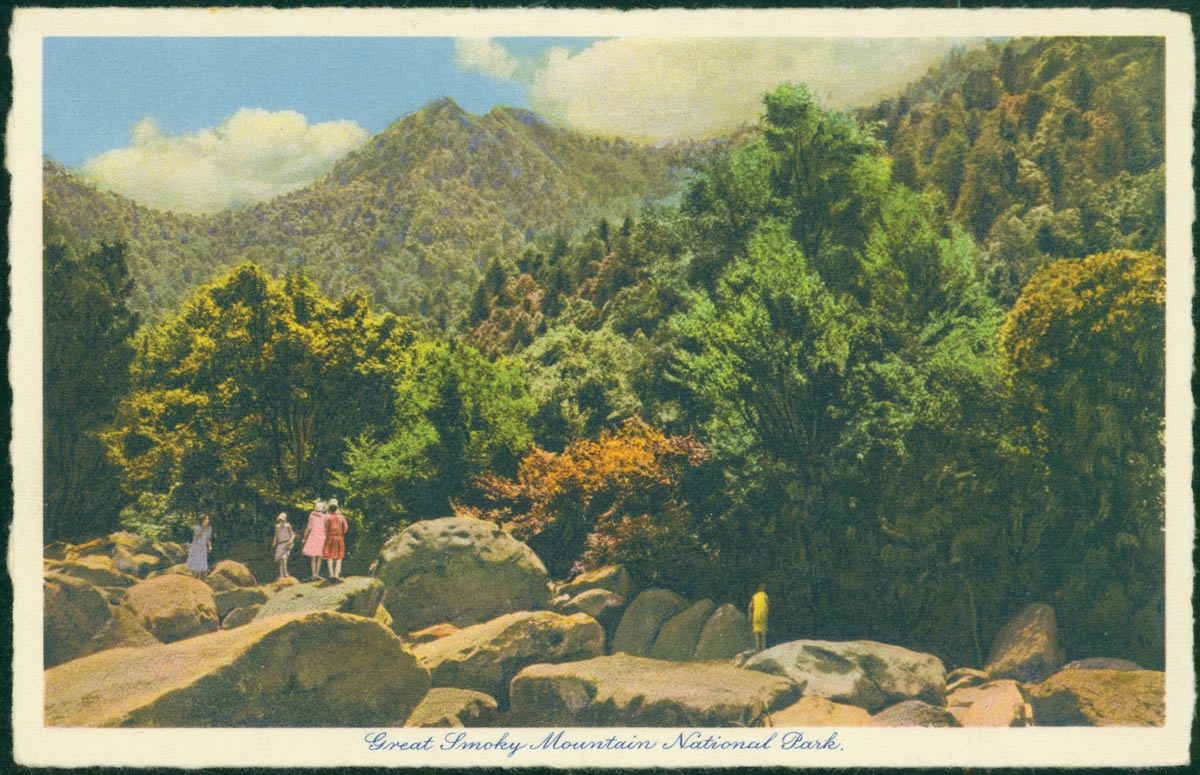

A postcard (top) featuring Masa’s image of visitors to the area, before it became the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, was used to promote the park after Masa’s death.

Photos Courtesy of the Pack Memorial Library,

Asheville, North Carolina

A postcard (top) featuring Masa’s image of visitors to the area, before it became the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, was used to promote the park after Masa’s death.

Photos Courtesy of the Pack Memorial Library,

Asheville, North Carolina

In 1961, a 5,685-foot peak in the park was named Masa Knob in his honor and is appropriately located on the shoulder of the 6,217-foot peak that bears the name Mount Kephart. The naming of Masa Knob was made possible by the continued efforts of the Carolina Mountain Club almost 30 years after his death — and 30 years after a peak was named for Kephart. That slight was not the first. Masa was the coauthor of the first Guide of the Smokies, but his name was removed from the credits only two years after the book was in print. And while Kephart recently had a biography published, he alone of the pair appeared in Paul Bonesteel’s documentary, The Mystery of George Masa — the source for much that is known about Masa today.

A single photograph — a permanent capture of a moment in time — has the power to transport and inspire the viewer. It also has the immense power to bring physical change. In Masa’s case, his legacy lives on in his photographs and the tangible places he helped protect. His images take us back to those ridges, waiting for the clouds to move so the mountains he loved could make their grand entrance. Hopefully over time, more of his vision will come to light.