A Career Beyond Description

By Brian B. King

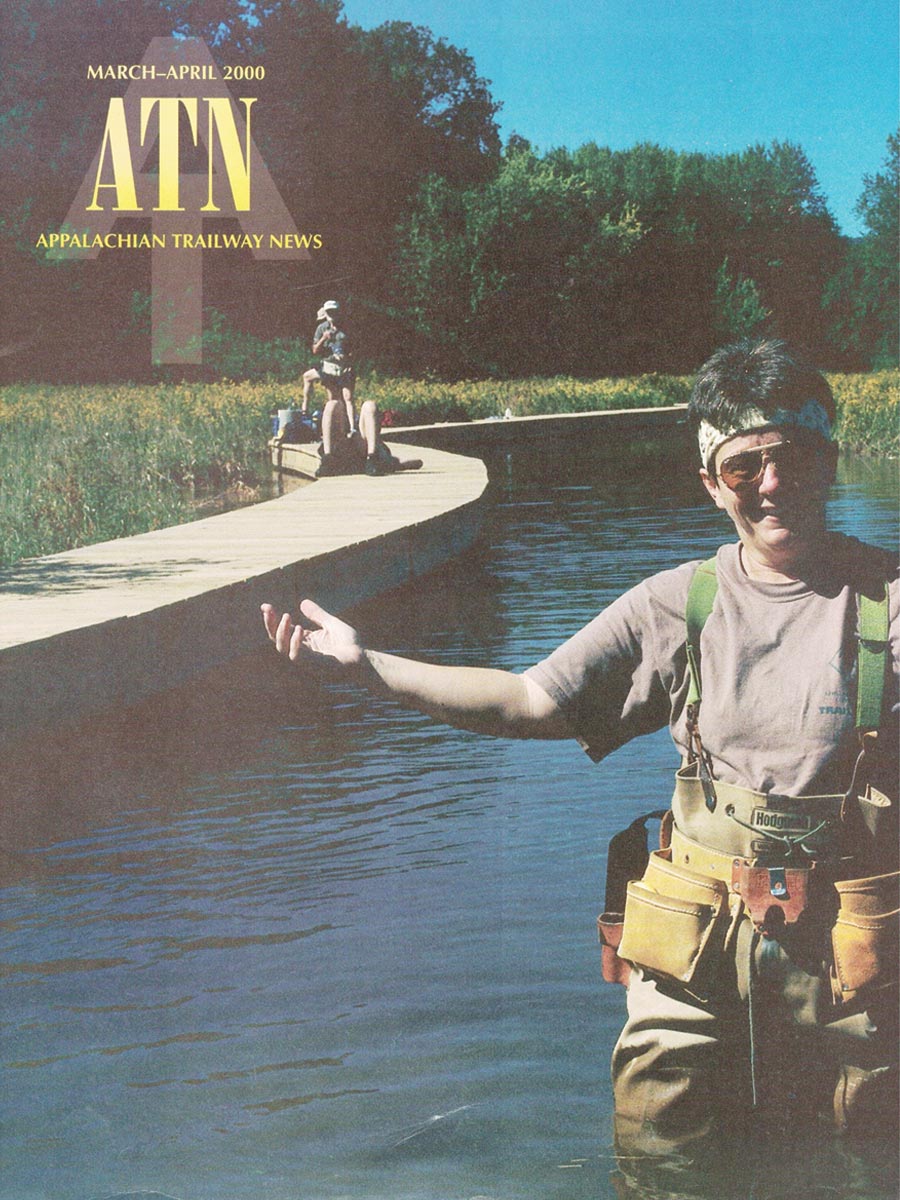

2000: Karen on the cover of Appalachian Trailway News — working to complete the Pochuck boardwalk and bridge project along the Trail in New Jersey following flooding from Hurricane Floyd — the whole project takes the Trail across a 3,000-foot swamp between Pochuck and Wawayanda mountains

Mid-80s: Bulldozers represent the “opposition” during a protest against a proposed ridge route — parts of which would run through farmland — in the Cumberland Valley

1989: Hanging the first sign for the mid-Atlantic ATC regional office in Boiling Springs

representative” 30 years ago probably was a bit incomplete, if not deceptive, as perhaps most such documents are. It would have focused on “serving as liaison” between the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) and agencies at the federal level – and in the region’s six states and between the ATC and the region’s 12 Trail-maintaining organizations, bookended by the relatively large New York-New Jersey Trail conference and the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club.

Helping presidents, testifying against murderers, rebuilding the first A.T. section, developing a mutually beneficial agricultural program near where huge warehouses were overtaking other fertile land, serving as local liaison for four ATC biennial conferences, dealing with the Trail’s two Superfund sites — none of that would be mentioned.

It then would have pointed to planning for Trail-corridor design, acquisitions of land for the permanent route, and the subsequent footpath relocations — in this case in particular, the 15-mile relocation across Pennsylvania’s Cumberland Valley, site of the most contentious valley relocation in Appalachian Trail history — its route finally selected by the National Park Service (NPS) in December 1985. Some legal battles were at hand, too. But, when Karen Lutz came to the job in July 1988, that particular relocation was in her blood, after more than a decade as an activist with the local PRO-TRAIL Coalition. The coalition was working to replace a roadwalk, where residential and commercial development was blossoming, with a scenic trail route through farmland and woodlands.

1998: Planting flowers in Harpers Ferry with then – Vice President Al Gore during an Earth Day celebration

2012: Celebrating the official designation of Warwick, New York as an A.T. Community

2013: Accepting the Keystone 20th Anniversary Award on behalf of the ATC for work on the White Rocks acquisition as an exemplary conservation project

Karen is retiring this fall and looking forward to “some hard-core outdoor stuff.” One of 106 successful 1978 thru-hikers, Lutz then went on to graduate work in recreation and parks at Pennsylvania State University, where researchers had supplied pivotal documents for Trail protection during Congress’ consideration of 1978 amendments to the National Trails System Act, specifically to help the A.T. Her thesis adviser, David Raphael, happened to be a new member of the ATC board, and her thesis happened to focus on A.T. hikers’ dietary needs and nutritional status during thru-hikes.

Raphael quickly introduced her to banker Craig Dunn, a longtime Trail volunteer in the valley then leading the coalition against CANT (Citizens Against the New Trail). Lutz helped with Washington trips to educate the state’s congressional delegation and spoke at often-raucous local public hearings on the routes under consideration. Later, she went on work trips, after the first tract was purchased in 1984, with the Mountain Club of Maryland and the Cumberland Valley A.T. Management Committee (later club, with the management assignment). “That was fun,” she says — not a common view among that battle’s alumni today but a signature of Lutz’s view of her 30-year career with the ATC. Meeting highly unusual challenges within the spiderweb of A.T. management gave her a lift – so maybe add “have fun” in that mythical job description.

Since late 1982, Lutz had been assistant parks superintendent for the York, Pennsylvania, city bureau of parks and forestry, supervising seven fulltime and 20 seasonal employees managing 23 parks, 11 softball fields, and an ice-skating rink. Soon after she joined the ATC staff, she and one part-time secretary moved into an antique resort cottage next to Children’s Lake in Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania — part of a major acquisition through the town the previous year by NPS and the ATC land trust. Today, that cottage is filled to the gills with staff members and files, and the A.T. route and its management are considered one of the valley’s jewels by local tourism authorities.

Meeting highly unusual challenges within the spiderweb of A.T. management gave her a lift – so maybe add “have fun” in that mythical job description.

“I am incredibly proud of our staff at the mid-Atlantic office,” Lutz said recently while reminiscing about those early days of enough open space inside to hold receptions for the neighbors, and of redoing the floors that today can barely be seen in the center area. “Across the arc of my career, I’ve tried to concentrate on the planning, the politics, the fund-raising, and agency compliance, and then hand it off to them” and Trail clubs. In that spirit, she retained such work as a two-year struggle to secure precedent-setting Pennsylvania Act 24, zoning legislation that protects the Trail after a hard, 10-year battle to prevent a sports car racing resort atop the A.T. in a northeastern township; an Earth Day 1998 spent at Harpers Ferry, guiding Vice President Al Gore and President Bill Clinton in a little Trail work before the speeches; and working behind the scenes to secure a Pennsylvania A.T. license plate that would benefit the ATC.

Some of those “hands off” situations consisted of: remediation of the denuded Trail above Lehigh Gap, a Superfund site in Pennsylvania; a technically complex one-and-a half-mile boardwalk and 110-foot suspension bridge across Pochuck Creek near Vernon, New Jersey; a 12-year, multimillion-dollar rehabilitation of the Trail on Bear Mountain in New York; a special bridge at Pa. Route 225; and a safety underpass where the A.T. crosses Pa. 944. That is her idea of fun — how else to describe figuring how to get 8,000 feet of a Trail meant for hiking, not wading, across a swamp?

Bridges have been a recurring feature in Lutz’s ATC career, including its most horrific chapter. In late September 1990, federal, state, and Trail officials dedicated one of her projects, a pedestrian bridge over busy five-lane U.S. 11 at the top of the valley, with only a handful of tracts still needed to complete the relocation off roads. A day earlier, Paul David Crews had been captured on the Trail, eight days after killing a young couple in a shelter on Cove Mountain, just a few miles north of the valley. The day the bodies were found, Lutz invited herself into the nearby state police barracks to offer her and the ATC’s assistance. She was not to be refused and for the next eight months worked hand-in-glove with investigators and prosecutors. It set a precedent for ATC assistance to law enforcement.

Karen with fellow ATC regional directors (from left) Hawk Metheny, Andrew Downs, and Morgan Sommerville at the 2015 Leaders in Conservation Awards Gala in Washington, D.C.

![]() photo by Nikki Lewis

photo by Nikki Lewis

“The fun stuff has mostly been working with some incredible colleagues, some wonderful volunteers, and more than a handful of dedicated think-outside-the-box agency folks.”

Thomas Coury was the barracks commander. He went on to become deputy state police commissioner, lead investigator at the September 11, 2001, crash of United Flight 93, lifelong ATC supporter, and later a top official in the first Homeland Security Department and Transportation Safety Administration. He recalled recently: “Karen quickly became a key member of the investigative team and provided extremely invaluable information based on her unique experience and knowledge of the A.T. and hikers. With great confidence, I can tell you that Karen’s expertise, knowledge, and dedication ultimately lead to the capture of a most dangerous killer.” Karen’s actions delivered a clear message to those who would consider crime on the A.T. and helped regain a sense of safety and security for those hiking the Trail. One of the things that immediately struck me about her was her truly deep concern and caring for the families and her passion for the sanctity of the A.T.”

The mid-Atlantic Trail weaves through the heaviest of all Trailside development and a web of interstates. “Incidents” are a part of the weekly work for all the staff there. Yet that built-in situation was far overshadowed itself by the satisfaction of dealing with the challenges, often unconventional ones. It is organizing and working with coalitions of state and local agencies, Trail club leaders, local activists, and others — often named after a mountain range or a particular preservation project along the region’s 594 miles — that Lutz spoke of, proudly, most often in a recent conversation. “The fun stuff has mostly been working with some incredible colleagues, some wonderful volunteers, and more than a handful of dedicated think-outside-the-box agency folks,” she said. And that has dominated her time in Boiling Springs.

“The Pochuck and the big bridge (and pedestrian underpass) projects are all things that I’ve loved doing,” she added, “and I really loved working with the Trail to Every Classroom program — and working with educators to use the A.T. as a teaching resource.” When she thru-hiked, the A.T. was 2,135 miles long and not worth the word “trail” through the Cumberland Valley. Until she retires, Karen Lutz can look out her office window at a 2,190-mile Trail just a few feet away, with a bucolic, duck-populated lake beyond it, and hikers passing most hours of most days, along an intact Cumberland Valley route worthy of the National Trails System Act. “It’s been an interesting career,” she observes.