Root Your Spirit

BASKING IN THE BENEFITS OF THE FOREST EXPERIENCE

Rustling leaves. Creaking trunks. The green smell of the earth after a light rain. Sunlight falling through the lacework of leaves.

Just reading a description of being in the forest might make you pause, take a deep breath, and feel the soft edge of peace that comes from spending time outdoors. You remember that feeling. Perhaps it’s been a while; or perhaps just yesterday you gave yourself a few minutes on a mossy rock. Either way, it tugs at you, asks you to return.

Being in the woods doesn’t just feel good, but is, in fact, good for you. If you’ve ever spent time in the forest yourself, you probably don’t need a scientist to tell you that. I grew up exploring the woods and climbing the trees of New Hampshire, and the idea seems, well, natural to me. My first climbing trees, the crabapple in our front yard and the red maple in our backyard, were like old friends. Depending on my mood, they offered comfort, exhilaration, or peace. I spent a good piece of every summer in the White Mountains hiking the trails, camping, and feeling utterly at home.

I heard the term “forest bathing” for the first time just a couple of years ago. It made me smile to think that something that felt so second-nature to me now seemed to have a new name, and that name was becoming a buzz word.

The Japanese government coined the term “forest bathing” (shinrin-yoku in Japanese) in the 1980s to describe the practice of spending time in the woods to soak up its health benefits. It does not involve water (unless you feel inclined to dip yourself in a stream or pond, in which case, by all means!), and it does not require strenuous exercise (we don’t all have to be thru-hikers or peak-baggers). Think, rather, of a slow, leisurely stroll, a pace that gives you time to notice small things, like a caterpillar crawling across a leaf or the unique scent of a pine forest — time to open your senses to the world around you. As John Muir wrote more than a century ago, “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home. Wilderness is a necessity.” And as Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “In the woods we return to reason and to faith.” It seems, according to recent scientific studies, that we return to health, too, as blood pressure and stress hormones fall and the immune system gets a boost. And then there’s that general feeling of wellbeing that has the power to lift your mood for days.

If you have spent some time wandering the Appalachian Trail, you have probably, like me, gotten a taste of what it means to be a forest bather without even knowing it. Next time you hit the Trail, give yourself a little extra time to wander — and to accept with deeper gratitude all the gifts our trails, trees, forests, and wildlands offer us, if only we’ll take the time. These gifts are pure grace.

As a poet, when I am struck by something, I try to turn it into words — and so the book Forest Bathing Retreat was born. Its impulse is not far from the sentiment expressed by Benton MacKaye when he articulated the purpose of

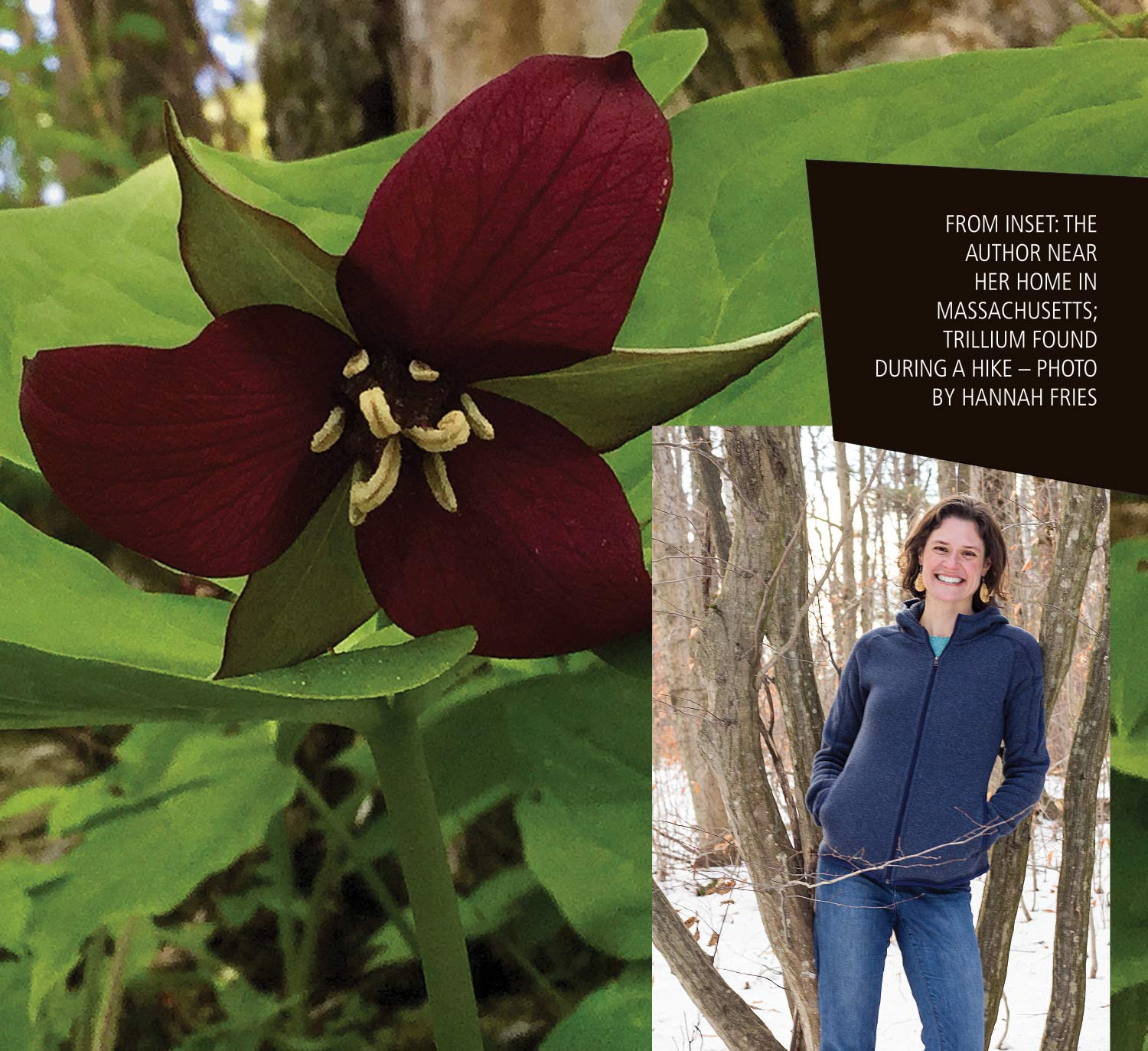

BY HANNAH FRIES

the Appalachian Trail: “To walk. To see. To see what you see.” That last part is important: to really see the things around us. This is a large part of what forest bathing is all about — and what filled my soul long before I ever heard the term. As a kid of eleven or twelve, I invented a solitary game for myself, the “noticing game.” The object was simply to wander around outdoors and see how many things I could find and truly see in an intentional way, with all of my senses. If you come along with me, I’ll try and show you what I mean.

Pause

Before you enter the woods, before you take another step, take a moment to scan your body and mind. Take a slow, deep breath. Then, begin with your toes. Wiggle them. Feel the soles of your feet pressing against the ground. Work your way up your body, letting your attention rest a moment on each part of you, noting where you feel tightness, tension, or stress. When you do, pause to take a few extra breaths. Imagine your muscles relaxing with each exhale. Unclench your hands. Bring your shoulders up to your ears, and then let them drop. Imagine a weight dropping with them, falling down your arms and flowing off your fingertips.

What sort of chatter is running through your head? Tell yourself you are going to focus on something else now. For a moment, just listen to yourself breathe. Put your hand on your belly and begin your breath there. Feel your chest expand and contract. Visualize your lungs inside your ribcage, filling with fresh air. Your lungs are filling with the breath of trees. As the trees breathe out, you breathe in; as the trees breathe in, you breathe out.

Open Up

Trees “breathe” in carbon dioxide and release oxygen and water vapor through tiny holes in their leaves called stomata, a word that comes from the Greek word meaning “mouth.” On one square millimeter of a leaf, there are 100 to 1,000 of these little mouths, all breathing. One mature tree breathes in 48 pounds of carbon dioxide each year — and the exhalations of two mature trees provide enough oxygen for you to breathe for more than a year. As you stand beneath the trees and breathe, imagine your own pores softening and opening, making you more permeable to the natural world around you.

Turn to the Wind

Turn now from your own breath, from the trees’ breath, to the breath of the wind — the little puffs and eddies, heaving storms and flowing currents that move in the ocean of our atmosphere. What does the wind carry with it today? A change in the weather? A bit of sweetness, or a wet chill? A puff of cottonwood seed, a swirl of dust, laughter from a nearby playground?

Reach Out

Now that you have found your center — your own breath — and let the forest puff its green breath across your skin, it is time to turn further outward, to send out your tendrils and roots and search for connection. As you walk through the forest, feel your own body react and respond. Invite the forest in through your senses. Pretend you have just been granted the gift of sight. Instead of looking at things, look for things. Play the noticing game — seek out small details that might otherwise escape your attention. Take delight in discovering them: The play of light through leaves or on water. Patterns in bark. Delicate plants growing close to the ground. The silhouette of a bird against the sky. The intricate shapes that ice makes. The winding work of insects. Bursts of lichen on rocks.

Listen

Get your other senses working now. Stop walking, close your eyes, and listen. You are not in a hurry. Do you hear rustling leaves or the creak of branches rubbing together? Birds? Scurrying animals? Trickling water? If it is very cold, you might hear popping sounds a tree’s sap freezes, creating frost cracks. As you listen, try to separate the layers of sound in your mind. Follow them to their source.

Smell

Have you ever said that the air smells “like fall” or “like spring”? What are you smelling? Dry leaves? Honeysuckle? Thawing snow? Wet earth and fresh green leaves? Get closer. Scratch a twig with your nail and smell the damp wood beneath. Crush a leaf of wintergreen and hold it to your nose.

Touch

The forest is full of textures — the soft fronds of ferns or mosses, the smooth bark of a birch or rough bark of a pine, an ice-cold stream, a slick stone. What does the ground feel like beneath your feet? Hard and rocky? Soft and needle-strewn? Perhaps you feel some mud suck at a shoe. Perhaps you take your shoes off — let your feet get in contact with the ground beneath them, skin to earth. Get a little risky. Nature is nothing if not sensual.

Taste, If You Dare

If you know what you’ve found is wild blueberry or blackberry. If a broken sugar maple bough is dripping sap. If you like the sour pucker of wood sorrel. Or just taste the air — the senses of smell and taste are closely connected. If you are near the ocean, you might detect salt on the breeze. If you are in a pine forest, you might feel as though you can taste the sun-warmed resin. If it is raining or snowing, stick out your tongue.

Look Again

Now pause and look at the trees again, at the plants and birds, squirrels and insects, and other living things around you. Remember that you are not the only one doing the sensing. You are being heard, seen, felt — sensed in ways you cannot understand.

Dissolve

As you take in the trees and all the life that revolves around them, as you begin to sense their intelligence, as you breathe their breath and touch their bark and listen to their clacking branches, you might start to feel the boundaries between you and them grow softer. Let it happen.

The herbs, the fir tree, I become part of it.

The morning mists, the clouds, the gathering waters,

I become part of it.

The wilderness, the dew drops, the pollen …

I become part of it.

As you watch a tree sway in the wind, let your knees and shoulders relax. Sway a little on your own stem. Let your imagination leap into another body. The body of a beetle. The body of a tree. What do you feel?

Root Your Spirit

Once you become practiced at being more physically connected to the world through your senses, you will likely find that something deeper inside you is reaching out for connection, too. Perhaps this is partly because your growing awareness causes you also to recognize your smallness. Your spirit, looking to re-root itself, sends out its feelers into the largeness of the world. It is an ongoing journey, this reaching out, and out again. And the universe, with all of its patterns and chaos and myriad threads of connection, is both terrifying and wondrous. Take a page from the trees: focus on being both rooted in the earth and searching among the stars.

Noticing the little things: roots and rock; beetle; song-bird egg; fern spores. ![]() Photos by Hannah Fries

Photos by Hannah Fries

Hannah Fries’s book Forest-Bathing Retreat is forthcoming from Storey Publishing in August. She is also the author of the poetry collection Little Terrarium and lives in the woods of western Massachusetts.