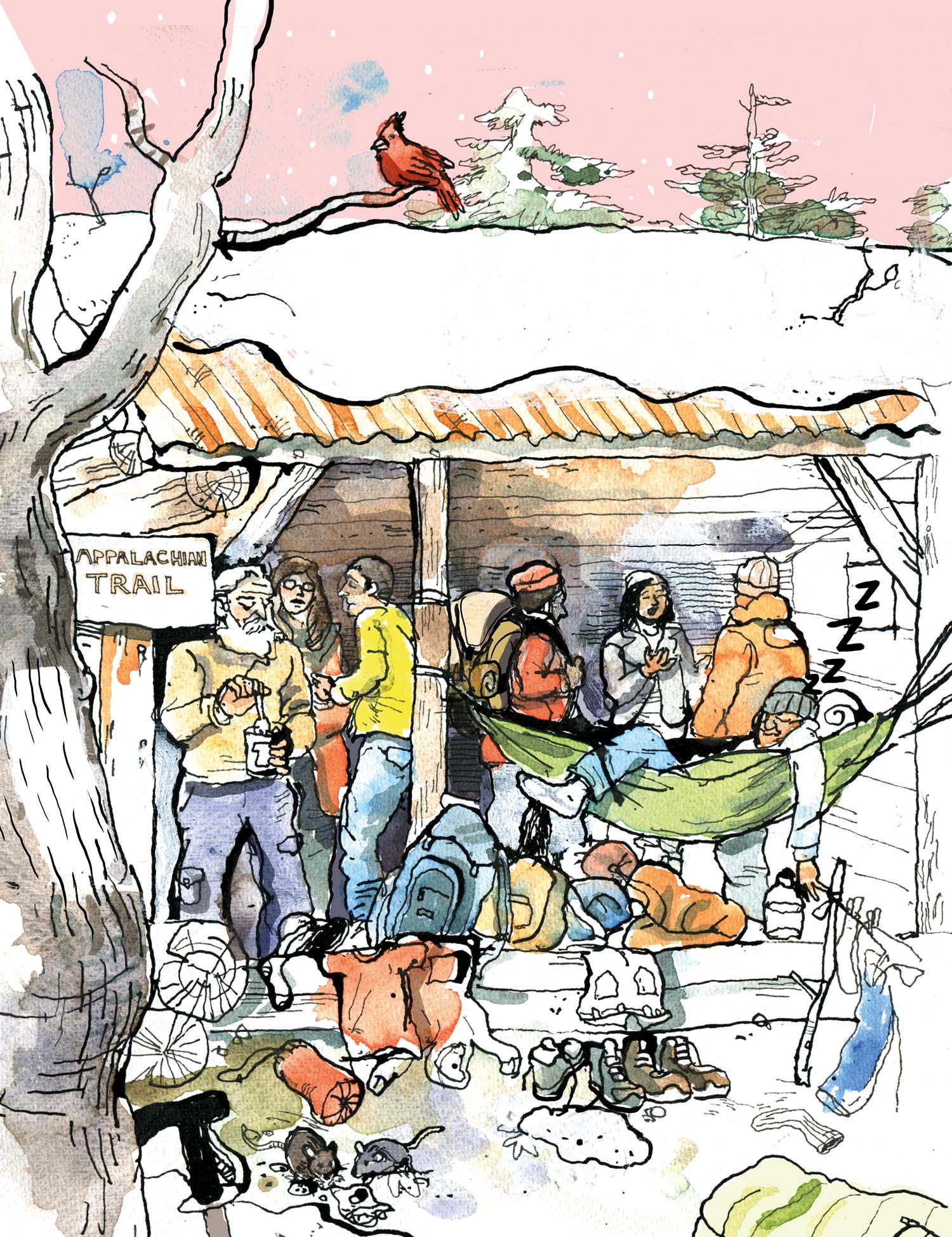

![]() illustration by alex hedworth

illustration by alex hedworth

By Lauralee Bliss

many of us have backpacked on a rainy day? Gear and clothing get soaked. Chills set in. Spirits are in need of a boost. The weather drives you to finish the day in a nice dry location like one of the many Trailside shelters that offer a refuge from the storm.

many of us have backpacked on a rainy day? Gear and clothing get soaked. Chills set in. Spirits are in need of a boost. The weather drives you to finish the day in a nice dry location like one of the many Trailside shelters that offer a refuge from the storm.

many of us have backpacked on a rainy day? Gear and clothing get soaked. Chills set in. Spirits are in need of a boost. The weather drives you to finish the day in a nice dry location like one of the many Trailside shelters that offer a refuge from the storm.

many of us have backpacked on a rainy day? Gear and clothing get soaked. Chills set in. Spirits are in need of a boost. The weather drives you to finish the day in a nice dry location like one of the many Trailside shelters that offer a refuge from the storm.

Shelter life, however, can quickly turn from a place of peace to one of distress. Case in point. I trudged in solid rain all day on the A.T. in southern Virginia on a section hike one summer week. My original camping destination quickly changed to the safety of a shelter that would provide a place to stay without having to set up a tent in the rain. After 18 miles, I arrived at the shelter. Ziploc bags of food greeted me from the small built-in area reserved for the shelter register. Garbage and remnants of burned trash lay strewn about the firepit. Soon after, two hikers came in. One hiker proceeded to string up a hammock that took over half the shelter. I didn’t make a big deal out of it as there were only three of us — until well after 10 PM as I lay snug in my sleeping bag when three soaking wet hikers came stomping in, looking for room. The hammocker stayed put, forcing the latecomers to set up right beside me. The hikers talked quite loudly while shining bright beams of white light across my face. I slept little with the hiker snoring beside me. The next morning, I noticed the hikers had left their food bags on the shelter floor. I wondered how many of those bags had holes in them from the mice. Exhausted by it all, I gathered my gear and left. Not a restful experience.

Fortunately, most experiences in shelters are not like this – and humanity is at its best with hikers understanding that courtesy and respect are key to everyone’s experience. And that kindred graciousness for fellow A.T. trekkers shines through, a good rest is had, and possibly some new friends are made.

Brook Shelter, White Mountains, New Hampshire

![]() Photo by Erin Donovan

Photo by Erin Donovan

Deep Gap Shelter, Georgia

![]() Photo by Laurie Potteiger

Photo by Laurie Potteiger

![]()

Shelters are generally first-come, first-serve to anyone backpacking the A.T., with no preference as to how long a hiker is out or how far one is hiking. Carrying a tent or hammock set-up is a necessity; you never know when a shelter might be full. A notable exception is the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP), which has special regulations for shelter use, with different options for long-distance hikers meeting specific criteria (refer to smokiespermits.nps.gov). Advance permits are required of all overnight hikers in the GSMNP, but can only be made about a month in advance. Shenandoah National Park in Virginia and Pennsylvania Game lands have some unique regulations, but do not require any actions in advance. Baxter State Park in Maine also has unique regulations (baxterstatepark.org). Northbound long-distance hikers are strongly encouraged to stop in the Monson Visitor Center (at the beginning of the “100 Mile Wilderness”) to make a plan for their stay in the park, which sometimes includes a stay at a lean-to. Section-hikers and others visiting the park for short stints are advised to make their reservations as far in an advance as possible.

If you are planning to arrive at a shelter after “hiker midnight” (usually considered to be after 9 PM), plan to tent. Hikers having to move around in a shelter to accommodate latecomers deprives everyone of needed sleep. If you know you are an early riser (before 6 AM) consider tenting also. Groups should also plan to tent rather than taking over an entire shelter.

![]()

When you arrive at the shelter, keep your gear contained in a small area. Putting up a tent inside a shelter means you’re taking up extra space someone else could use, and putting up a privacy shield that creates a weird vibe in a communal space. Even if you think you may be the only one in residence, chances are you won’t. On stormy nights, be prepared for a packed house. I’ve seen hikers work together on a rainy evening to make room for all, allowing for great kinship and a new hiker family. Having a headlamp that has a night feature (red in color) rather than a simple white beam that blinds your neighbor will make for more pleasant surroundings. If you know you snore, chances are you will have lots of unhappy folks in the AM if you stay in the shelter. Have mercy and set up your tent. Earplugs are a good idea for shelter dwellers. Cook and eat away from the shelter. Some stoves sound like jet engines when fired up (and can wake the dead), and even a small crumb of spilled food can be a meal for a mouse and keep him coming back for more. Take great care with alcohol stoves as flare-ups can damage wooden shelter floors and picnic tables.

Refrain from making calls on your cell phone in the shelter area and move a good distance away to make your call. If you hike with a dog, the most considerate thing is to tent, especially if your dog is muddy, very active, or is prone to barking, but at least ask first if your dog is welcome in the shelter. Always keep your pooch on a leash. Some hikers are allergic, fearful, or don’t want dogs near their gear or food. Refrain from smoking cigarettes, e-cigarettes, or cannabis in a shelter. It’s just common courtesy, whether the substances are legal are not. Use shelter logs for your Trail reflections and not the shelter walls or inside the privy (it is illegal to deface shelter walls). Use the broom to sweep out the shelter when you leave in the AM to ready it for future occupants.

Chestnut Knob Shelter, Virginia

![]() Photo by Kaleigh Toole

Photo by Kaleigh Toole

![]()

The mouse hangers and hooks in shelters are for packs and gear. If storing your pack in a shelter, make sure zippers are open and all food and toilet paper is removed. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) recommends bear-resistant food canisters as the best way to protect your food and “smellables” from bears and all other critters, as well as protecting bears from the consequences of becoming habituated to hiker food (meaning the bear must be relocated or euthanized). Otherwise, hang all food away from the shelter either by bear bagging (using the “PCT” method, recommended by the ATC) or by devices provided in the shelter area such as cables, poles, or bear boxes. Do not leave behind excess food as it attracts animals and makes more work for Trail volunteers. Use the picnic table to eat your food. Carry out all food and trash. And don’t burn trash (any fragments left attract wildlife) or garbage in the firepit.

![]()

Help keep the area in the immediate vicinity of the shelter clean by brushing your teeth, urinating, and washing up at least 100 feet away, and 200 feet from a water source. Most shelters have privies; use them. Only toilet paper should go down the privy hole, all other hygiene products should be packed out in a sealable bag. When you can get some distance from the privy, shelter and water source, wash up with a bit of biodegradable soap and water to reduce the chance of spreading highly contagious stomach bug or norovirus. Following these and other Leave No Trace Principles will make life better for the environment, you, and your fellow trekkers.

For more information and tips visit: appalachiantrail.org/shelters

Leave No Trace etiquette: lnt.org and appalachiantrail.org/lnt. Learn more about the ATC’s A.T. Camp program at: atcamp.org

Lauralee Bliss is an A.T. 4,000-miler both north and south, worked as a ridgerunner for Shenandoah National Park, and is a speaker and the author of Mountains, Madness, and Miracles – 4,000 Miles along the Appalachian Trail. Visit: blissfulhiking.com