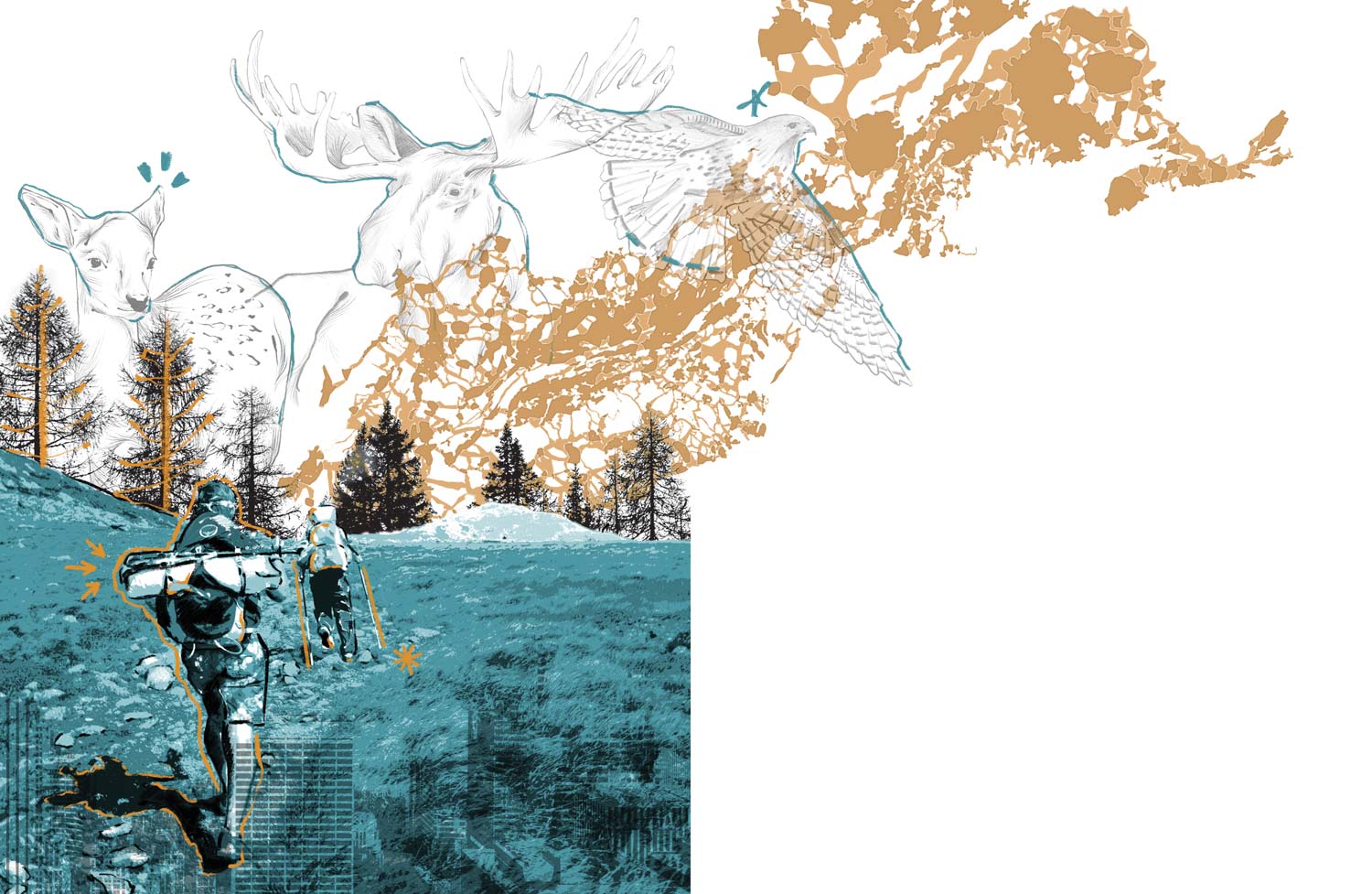

The year I took that picture, I was migrating, moving through the A.T. landscape at the modest pace of 15 to 17 miles per day. My dad was my hiking partner. We were tiny dots on the map as we walked, seeking Katahdin, Maine’s greatest mountain and the northern terminus of the Trail.

The year I took that picture, I was migrating, moving through the A.T. landscape at the modest pace of 15 to 17 miles per day. My dad was my hiking partner. We were tiny dots on the map as we walked, seeking Katahdin, Maine’s greatest mountain and the northern terminus of the Trail.

Two years after my time on the A.T., I’m still grappling with the fact that the Trail is not just a contiguous footpath and a thread that links 14 states, but that it is also something that drives landscape conservation across the eastern United States. As hikers and outdoor enthusiasts, we embrace the recreational values that the A.T. provides while sometimes failing to understand its more complicated side. “The Trail is a simple footpath,” I’ve heard. Well, yes — but it’s also much more.

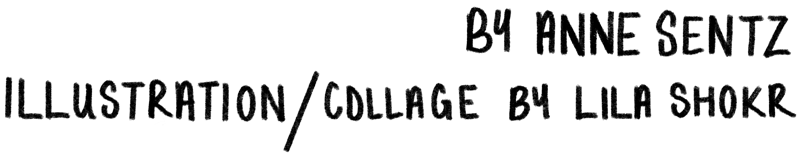

We have to acknowledge, and protect, those places that will sustain plants, animals, and all natural life in the face of a changing landscape.

We have to acknowledge, and protect, those places that will sustain plants, animals, and all natural life in the face of a changing landscape.

Most of us have likely witnessed things like this before: a wild animal figuring out where to go when something foreign is in its path. It tugs at our heartstrings a bit, reminding us of those times when we’ve felt trapped, boxed in, and the opposite of free. It’s a type of empathy that can drive us to act, because we realize life isn’t just about us — instead, we come to understand we are part of a system, and the prosperity of that system depends on individual actions that do have an impact overall. For example, we wouldn’t necessarily label a single fence or road inherently “bad,” but when that fence or road blocks the natural travel of an animal, it gives society an opportunity to consider the impacts.

Landscape conservation embraces the idea of connectivity. On the surface, an effort to successfully protect a large swath of diverse landscape might look like the connection of different wild spaces that native animals need to survive. What it takes to get to that success story, however, is full of twists and turns as people work together to embrace a type of cross-border work that is quite multifaceted. As the Network for Landscape Conservation — a practitioner’s network that seeks to advance and implement the practice of conservation at the landscape scale — says, “In a hyper-polarized world, the landscape conservation approach leverages literal common ground — our landscapes — to promote dialogue and exchange across perspectives and values to find figurative common ground.”

When you consider the A.T. as the backbone of a large landscape conservation effort along the Eastern Seaboard, it is a natural fit. Along its 14 states, the Trail connects farms, forests, rolling hills, deep valleys, open pastures and more; managing that landscape diversity requires thoughtful consideration of how these regional differences fit like puzzle pieces into a larger 2,190-mile footpath. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) has been promoting a type of landscape conservation since its beginnings in 1925, but as we enter a new decade, one with accelerating challenges due to habitat loss, forest fragmentation, and climate change, we must demand more from everyone who lives, works, and plays within this landscape, and especially from those who love the A.T.

Conservationists recognize the impacts of these challenges on the way our public lands are managed. Johnathan Jarvis (former director of the National Park Service) and Gary Machlis (former science advisor to the director of the National Park Service) write in their book: The Future of Conservation in America: A Chart for Rough Water, “The paradigm of protection and restoration that has guided management of parks and public [lands] for the last fifty years is no longer fully viable in an era of climate change.” This begs the question, “What’s next?”

Lately, the ATLP has made a concerted effort to inject more scientific analysis into A.T. landscape — or as we lovingly call it, Wild East protection, and to do that, the group joined forces with the Open Space Institute (OSI), a New York-based organization that supports conservation on a permanent, landscape scale. Late last year, a small team from OSI, led by Abby Weinberg, director of conservation research, worked to identify where land protection efforts could make the biggest difference in conserving resilient forests and wildlife movement corridors. These two things are hallmarks of large-landscape conservation: forested land connects habitats and facilitates species migration, which is becoming more and more important as species adjust to climate change and human impacts to their landscape. In the United States, scientists have observed the migration of native species is shifting, amounting to an average of 11 miles northward and 36 feet upslope per decade. To avoid the continued loss of species, plants and animals must have a connected landscape on which to depend, and it is imperative that this landscape has options for movement (meaning forestland is paramount).

“The amazing thing about the Appalachian Trail is that it’s the only way to get through the eastern [U.S.] landscape with any consistency and long-range connectivity. There aren’t many dead ends,” says Weinberg. “When movement is needed, those species can move northward and upslope.”

Consider the A.T. as the backbone of a large landscape conservation effort along the Eastern Seaboard.

Consider the A.T. as the backbone of a large landscape conservation effort along the Eastern Seaboard.

OSI’s analysis used data provided by the Nature Conservancy (TNC), an organization that is leading efforts around the world to tackle climate change. Mark Anderson, director of conservation science at TNC, addresses tough questions about the impacts of a changing climate on our landscape — and humans — in the report: “Resilient and Connected Landscapes for Terrestrial Conservation.” TNC defines climate resilience as the capacity of a site to maintain its biological diversity, productivity, and ecological function, even as the climate changes. It might sound a bit hard to digest, but what it means to us is this: we have to acknowledge, and protect, those places that will sustain plants, animals, and all natural life in the face of a changing landscape.

When it comes to the A.T., OSI’s work revealed that 57 percent of the Trail’s landscape scored above average for climate resilience, but only 34 percent of those lands are actually protected. This is important information that the ATC and NPS can take back to the organizations within the Appalachian Trail Landscape Partnership to assist in prioritizing land protection efforts. “While it would be ideal to protect all resilient resources, limited funding, capacity, and time make prioritizing important,” Weinberg writes in OSI’s report to ATC.

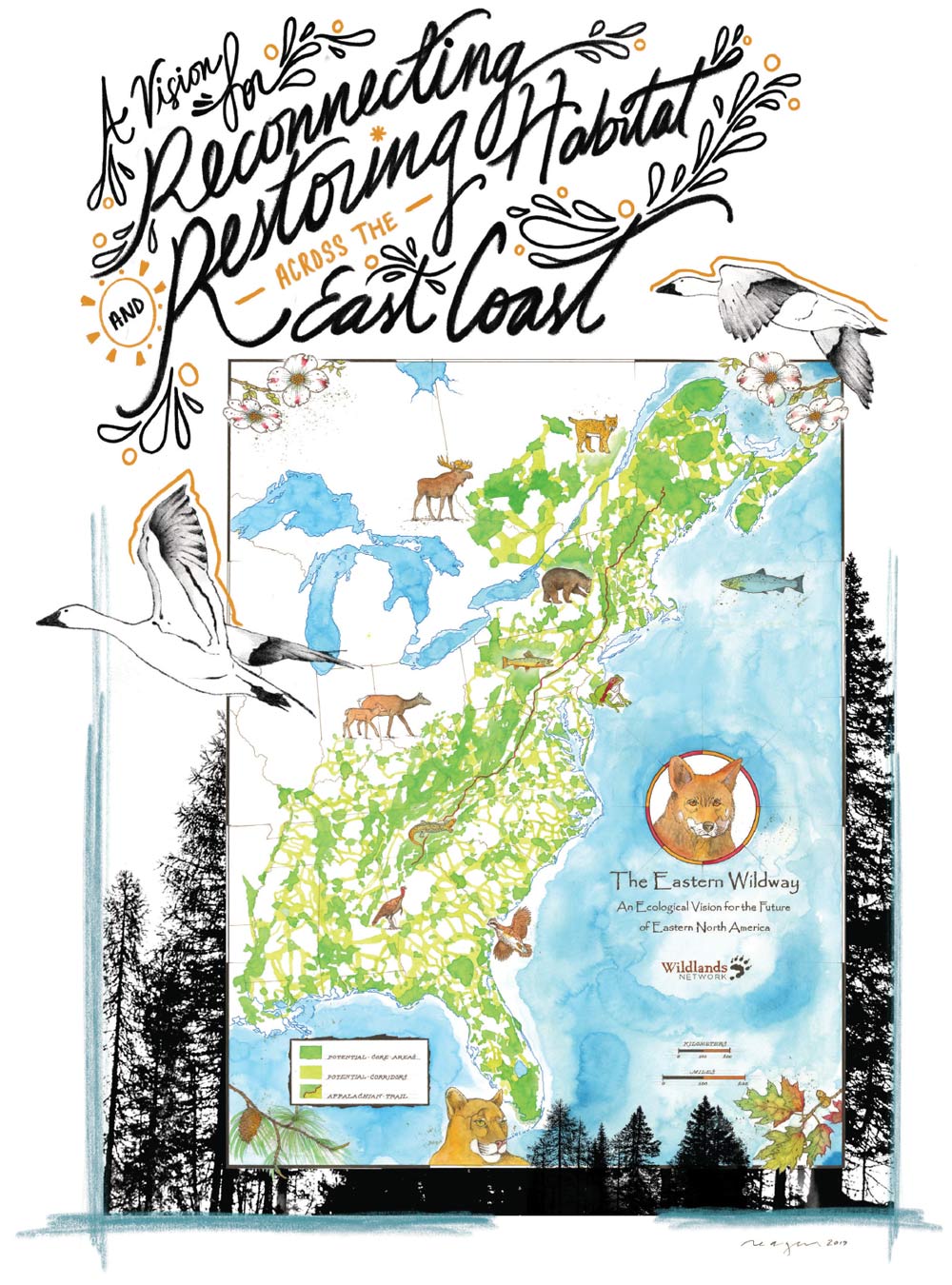

“We’re proud of the way we’ve used the best available science to map out a robust vision for saving 85 percent or more of the biodiversity of the East Coast from extinction,” says Ron Sutherland, Wildlands Network chief scientist. “If protected, the Eastern Wildway habitat network would allow almost all native species to survive the ravages of rapid climate change and habitat destruction.”

ATC is a partner to the Wildlands Network, and both organizations seek to ensure the A.T. landscape remains contiguous and intact so native species can thrive. Both organizations also strongly support legislation like the Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act of 2019, which was introduced by House A.T. Caucus founder and Co-Chair Rep. Don Beyer. This legislation would allow for the designation of wildlife corridors on federal public lands, and it would also support collaboration between the federal government, state agencies, and private landowners to preserve wildlife corridors.

Protecting biodiversity is dominating the conversation when it comes to landscape conservation, and for good reason: one in five species in the U.S. is threatened to become extinct because of climate change and its impacts. For the Wildlands Network to realize its vision of an Eastern Wildway, the continued protection (and expansion) of our intact landscapes is necessary.

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy has been promoting a type of landscape conservation since its beginnings in 1925, but as we enter a new decade, one with accelerating challenges due to habitat loss, forest fragmentation, and yes, climate change, we must demand more from everyone who lives, works, and plays within this landscape, and especially from those who love the A.T.

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy has been promoting a type of landscape conservation since its beginnings in 1925, but as we enter a new decade, one with accelerating challenges due to habitat loss, forest fragmentation, and yes, climate change, we must demand more from everyone who lives, works, and plays within this landscape, and especially from those who love the A.T.

As a relative newcomer to the world of landscape conservation, I often look toward more experienced conservationists and land managers, hoping to see the answer to the complex process of landscape conservation tied up with a neat bow. But maybe the answer will never be simple, and perhaps it can be found in the details of how we align our collaborative work. We must trust science; we must actively listen to the needs and desires of our communities; we need to communicate how recreationists can become conservationists; and, overall, we need to embrace a sense of place that does not set up the false dichotomy of “people versus nature.”

From the Stratton Mountain fire tower, you can see rows and rows of green. More than two years ago, when I stood on the platform, I felt a deep sense of responsibility for the landscape that had changed my life. I also felt apprehension, because I had no idea what was to come. I know what’s possible — you do, too — if we are able to work together to sustain our communities and important natural and cultural values.

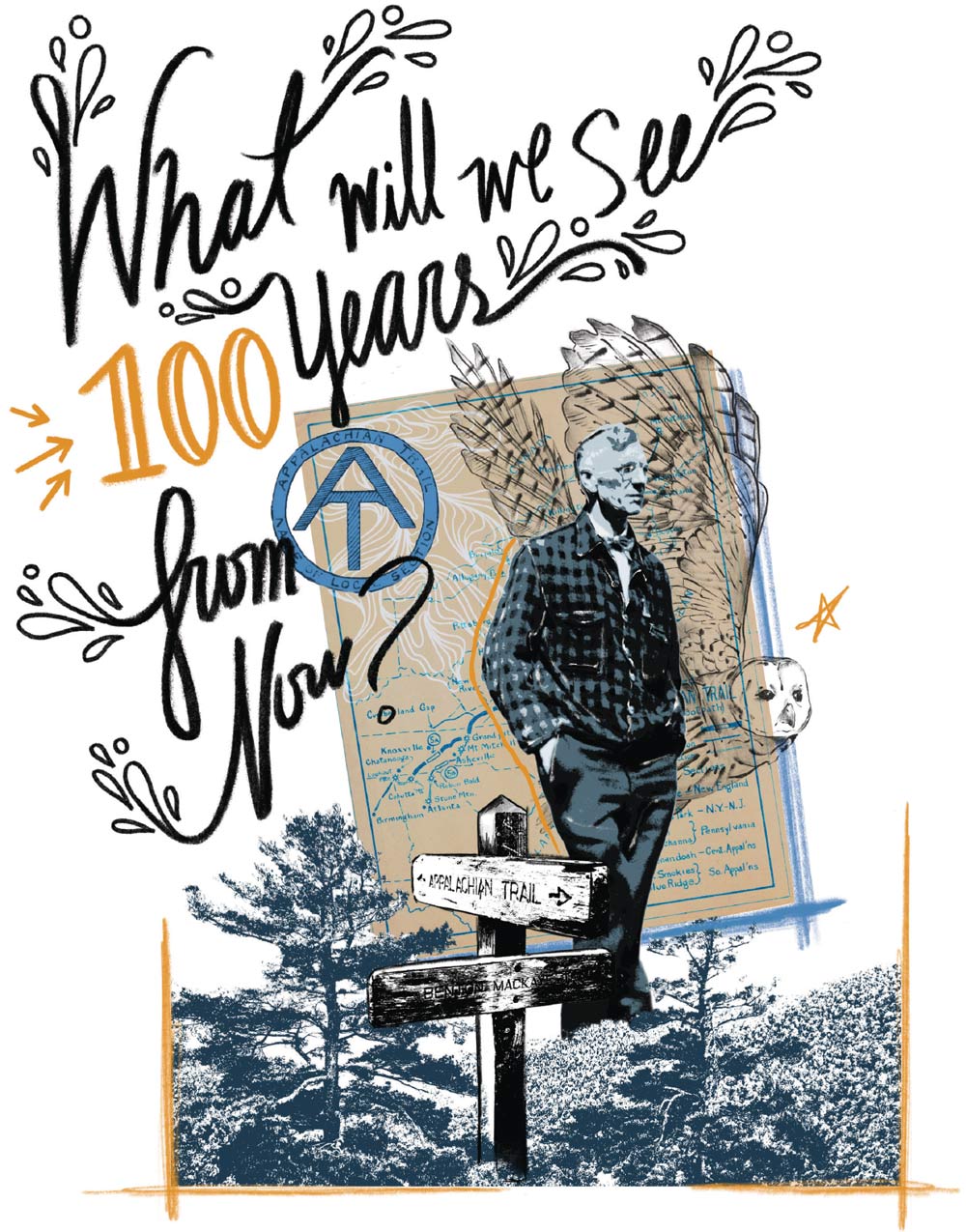

In his essay An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning, MacKaye wrote, “Let us assume the existence of a giant standing high on the skyline along those mountain ridges, his head just scraping the floating clouds. What would he see from this skyline as he strode along its length from north to south?”

What will we see 100 years from now?