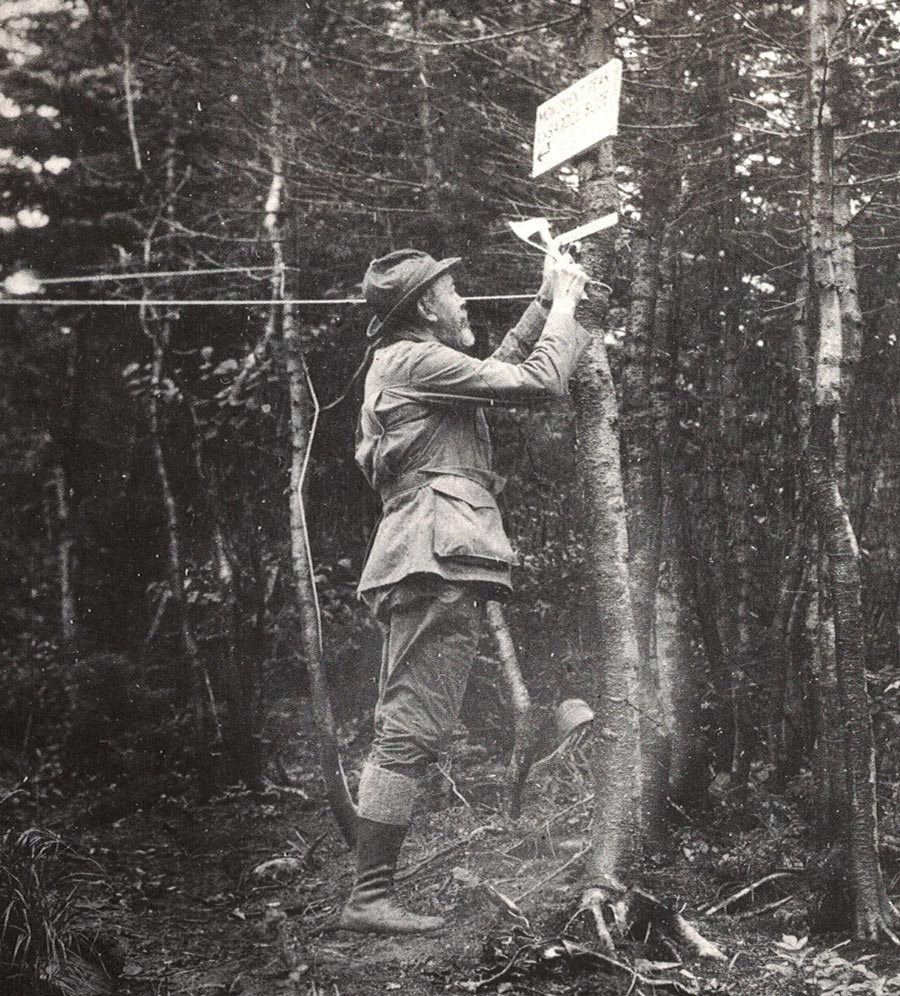

Clockwise from top left: Percival Baxter; Myron Avery; Avery with measuring wheel on the Knife Edge in 1933 — on his way to set his first summit sign

![]() courtesy Maine State Library

courtesy Maine State Library

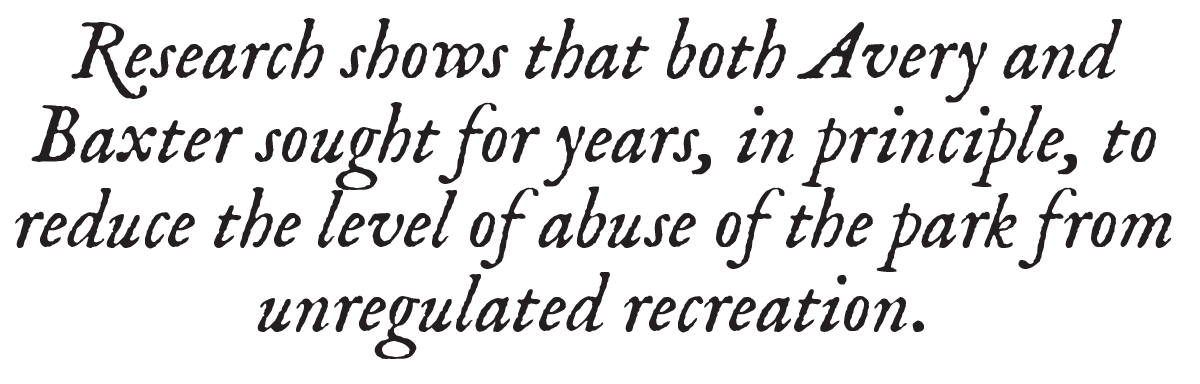

Those leaders were both graduates of Bowdoin College and Harvard Law School, basically a generation apart. Both were passionate about, if not obsessed with, the “greatest mountain” as central to their present times and most certainly to their legacies. One could pursue their story as a sort of a love triangle gone sour: jousting knights — Percival P. Baxter and Myron H. Avery — in a quest for the role of Katahdin’s steward.

Or perhaps it’s a tale of class rivalry. Baxter’s politician father made his fortune in the canning industry along Maine’s coast, the inherited portion of which his son used to buy the 200,000 acres now comprising Baxter State Park. Two hundred miles up that coast from Baxter’s Portland, Avery’s father managed sardine-canning operations for a local owner. It was the town’s economy. Myron was never interested, his own siren being the mountains 150 miles to the northwest and its heart: a mile-high, glacially scarred, granite monolith rising above the evergreens. The history of the relationships between Baxter — the man and the park — and the multilayered creation and management of the Appalachian Trail is neither that simple nor straightforward, however.

It is historically quaint, even ironic, that the first known path given the name “Appalachian Trail” was cleared in 1886 across the northern basins below Katahdin and identified as such for 40 years. Percy Baxter was 10 years old in 1886. Myron Avery would not be born for another 13 years, the year after Baxter graduated from Bowdoin. Benton MacKaye was seven.

The Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC) commissioned that first Appalachian Trail between camps, according to Katahdin: An Historic Journey by John W. Neff, former Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) board member, former Maine Appalachian Trail Club (MATC) president, and two-decade maintainer of the A.T. up Katahdin until 2004.

The son of one of those 1886 trail-blazers, 14 years later, would clear the Hunt Trail from the family farm and camps at Kidney Pond in the southwest quadrant of the Katahdin core up to the summit. It was subsumed by the modern A.T. in the 1920s and 1930s. Large parts of the basins were and are remote and unspoiled, but much of the land below Katahdin was spotted with farms, sporting camps, primitive trails between, and serious lumbering and timbering operations on all sides — hardly “unspoiled by man” or completely wild.

Records of the relationships involved are somewhat scattered and clearly incomplete. The ATC archives have some documents, including one of Avery’s personal scrapbooks that includes part of his life-long collection of Katahdin images. He was a prodigious correspondent and record-keeper. The Maine State Library has at least an equal number, much of it liberated from the ATC’s archives and since digitized by David B. Field, an A.T. volunteer for more than half a century, former MATC president, former ATC chair, and still a preeminent expert on all things Maine A.T. According to Howard Whitcomb, a Neff coauthor at Friends of Baxter State Park, extensive Baxter State Park records, on the other hand, were lost in a January 1967 fire at the home/office of then-Superintendent Helon Taylor, a key figure in the 1930s scouting of the A.T. elsewhere in Maine.

Monument Peak in 1931, before it was named Baxter Peak

Throughout his school-year summers, Avery was drawn to Maine’s mountains, with photographic evidence of treks on the water and up the rocks into his Harvard years — although more of that evidence is of trips north and east of Katahdin than on the mountain itself. Avery left many images of logs and loggers on the Penobscot River, then the gateway (by bateau) to the south side of Katahdin, with Katahdin in the clouds as background.

A staple of A.T./ATC folklore — much of it established by Avery himself — is that Benton MacKaye proposed in 1921 that the northern terminus of his proposed Appalachian Trail be Mount Washington (true) but that, when Avery took control of the project in 1930, the passionate Mainer alone insisted that it be “moved” to Katahdin (not entirely true).

“Maine to Georgia” became the project’s official motto by 1923. In 1924, a year before the ATC was formed, Arthur C. Comey, head of the New England Trail Conference (NETC), issued a progress report on the A.T. project that clearly showed a proposed

trail from Katahdin to Georgia, with 13 miles completed in Maine. The proposed A.T. project, as far as New England went, was completely in the hands of NETC and AMC at the time.

It was Comey who brought together MacKaye and Major William A. Welch — progenitor of that motto and the A.T. diamond logo, and the ATC’s first chair — and later Judge Arthur Perkins, the ATC’s first truly active chair. Perkins was another leader who first became enamored of trail-building while on Katahdin’s slopes, where he in 1927 mounted its first A.T. signs, just below treeline. Comey would serve on the ATC’s board from the beginning in 1925 until 1935 — the year Avery and MacKaye acrimoniously parted ways over the purpose of the A.T., with AMC leaders also essentially on the side of A.T. progenitor MacKaye.

Beginning in 1927 — just as Avery, an AMC member since 1926, came to the Trail project and contacted Perkins — letters between Avery and Comey were beyond caustic, beginning that November with a fight over names on Katahdin maps. Those tensions, among others, would come into play soon enough in determining the future of then-unconsummated Baxter State Park. (Acquiring Katahdin for the public was hardly unheard-of. Before the agency was even three years old, the National Park Service was exploring — with little local support — the idea of making it a national park. Such even was advocated in 1916 in a speech on the U.S. House floor, weeks before the NPS officially existed.)

The existing correspondence does imply that, by no later than August 1929, the project leaders — documented in a Comey letter to Perkins — were leaning toward pulling back to Mount Washington, because it was too difficult to build a trail through remote and dense western Maine and local interest was lacking. Comey had just scouted from Old Blue to Indian Pond after a 1925 such trip from Grafton Notch to Old Blue. He noted, “There are many interests in Maine against such a trail, notably the wildland owners, who dictate much of the state’s policy.” An additional factor was that, in those early days, most of the A.T. was blazed across private lands with the tacit agreement of the landowners, a verbal handshake, and the extensive timbering operations there would have restrained a hiking path.

Judge Arthur Perkins mounts the first A.T. signs on Katahdin in 1927

![]() Photos courtesy ATC Archives

Photos courtesy ATC Archives

But, Katahdin was still special. “[W]ith local leadership (politically) some outsiders would doubtless be glad to work on the actual trail, as we have done at Katahdin,” Comey wrote, before 1929.

Avery, who became involved in 1927 and was hard-charging from the start, did push back by 1930 as the ATC’s acting chairman. Following on the initiatives of Walter Greene, who had blazed the Trail from Katahdin to Monson, Avery began a 77-mile scouting Trip with his trailblazing crew from the Potomac A.T. Club (PATC), by placing a summit marker atop Katahdin on August 19, 1933. Existing letters show that Percival Baxter blessed that effort in a letter three months later after personally inspecting the route to the summit that fall.

Two years later, with a larger expedition and back-up from the state and federal forest services and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which officially adopted the Maine section of the A.T. that year, he installed another sign and measured and nearly completely opened and blazed the remaining new A.T. throughout Maine. Those PATC members during this trip also formed the Maine Appalachian Trail Club (MATC), with Avery, after Greene’s death, the head until his death (as he was for many years the head of ATC and PATC, too). The ATC/Avery immediately assigned maintenance of the A.T. from Grafton Notch to Katahdin to MATC, but that wasn’t quite accepted on the ground for years.

Avery (center) at the 1939 conference with longtime ATC secretary Marion Park at the Daicey Pond Campground

![]() By Mark Taylor

By Mark Taylor

Notes and measuring wheel in hand in that fall of 1933, Avery was soon in more pitched battles with both NETC and AMC over who would write and produce the official guides and maps for the Katahdin section of the A.T., which meant dual publications for a period before and after. The inland-fisheries commissioner wrote Avery that game wardens in 1926 or 1927 had created an unmapped trail from Katahdin to within five or six miles of the Kennebec River. AMC published its first Katahdin guide in 1917, with contour maps in 1925. The ATC began publishing trail maps for Katahdin in 1927, before Baxter had bought his first acre.

Avery nailed wooden markers in 1928 from the summit to Ripogenus Gorge, along what became the park’s southern boundary (Golden Road), according to a February 1930 Avery article in Mountain Magazine. In 1928 and 1929, Avery was churning out what the Maine Library Bulletin called “Katahdiniana” for the AMC’s magazine; In the Maine Woods, the Bangor and Aroostock Railroad’s premier magazine of the day; and numerous small journals.

Avery’s copy of the rival 1933 NETC Maine guide, full of margin notes for other states, still stated, however, that the A.T. ended at Grafton Notch, “the end of the Appalachian Mountain Club trail system.” The introduction mentioned Greene’s leadership and the Maine Forest Service and Avery’s writings elsewhere, but not the ATC or Baxter himself. Avery wrote chapter six, which was more optimistic about progress in Maine. Then, he produced his own typescript guide. That August of 1933, six days before he did it, Comey wrote Avery: “I assumed the northern end of the A.T. was the summit of Katahdin. If so, suggest you get very official permission to place your sign there, as I understand that Baxter has removed the monument and might have his own ideas.” (Baxter Peak had been named Monument Peak before the state accepted the first parcel from the former governor in 1930.)

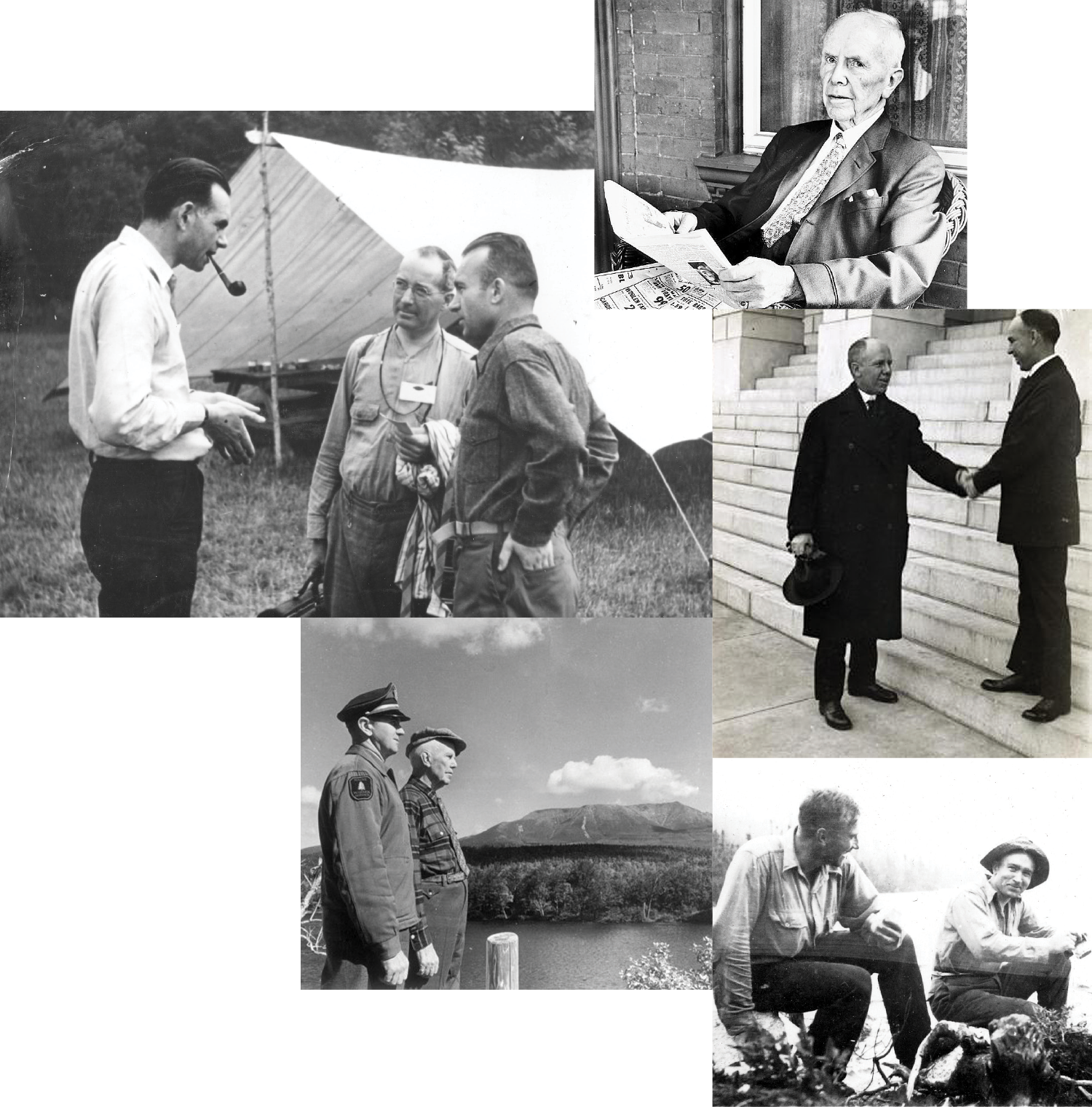

In November, Baxter wrote an AMC intermediary of Avery, “I am pleased to learn that the Appalachian Trail has been marked right through to Katahdin, and of course I have no objection to having your trail signs placed on the land that I have conveyed to the State. In fact, I am pleased that this has been done.”

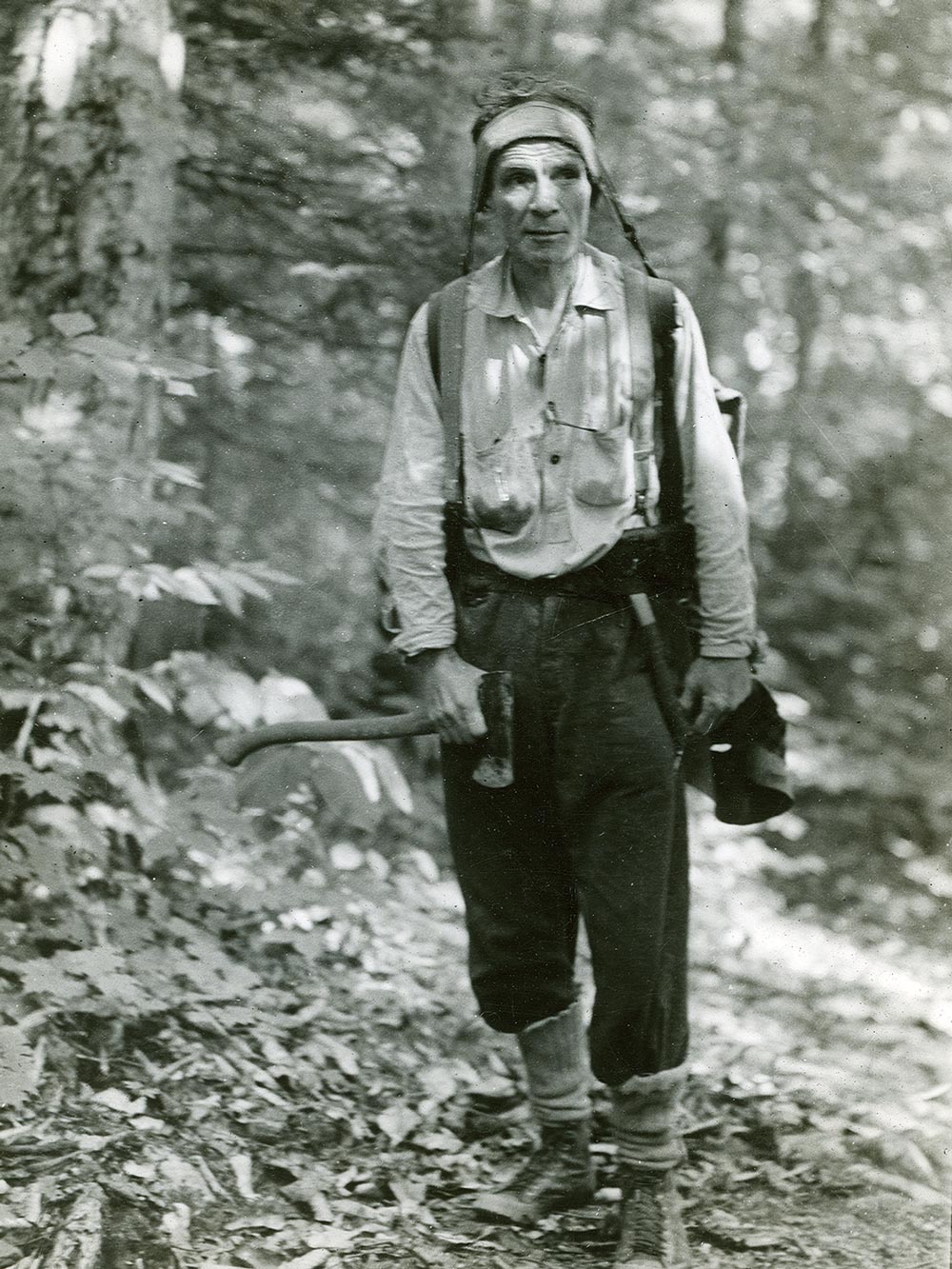

Walter Greene blazed the Trail from Katahdin to Monson

While Avery was in college and then Harvard Law, Baxter, who had first gone fishing below Katahdin in 1903, was in politics. The summer of 1920, as Avery had left Bowdoin, Baxter made his first ascent of Katahdin — partly a campaign photo-op of the day but also a pitch for Baxter’s decade-old drive to create a state park there, a pitch that failed in the legislature year after year while he was in office. A long-time state legislator, he was poised to become the president of the state senate — next in the line of succession to the governorship the following winter, when the incoming governor died and Baxter became Maine’s chief executive.

Baxter did not stand for election in 1924 but vociferously opposed R. Owen Brewster, who would succeed him in Augusta and in 1926 sabotaged his bid for a U.S. Senate seat he thought then would be the source of his legacy. (Two years later, Baxter returned the disfavor.) By 1924, Avery was finished at Harvard and en route to Washington, D.C. for a job as a Navy admiralty lawyer — his lifelong day job, but with at least annual trips to Katahdin.

A 1925 bill in Congress to make the Katahdin region a national park went nowhere. By 1930 —after previous corporate leaders had rebuffed him and after the 1929 stock-market crash — Baxter convinced executives of the Great Northern Paper Company to start selling him pieces of its land on and around Katahdin. At first, it was the summit and a narrow corridor comprising 5,960 acres and “none of the existing approaches” to the top, Avery later noted.

In 1929, a disabled Judge Perkins was beginning to cede ATC leadership to Avery. The A.T. was already established and marked on Katahdin, on and outside the original Baxter conveyance, surviving records show. The first and succeeding deeds from Baxter to the state are significant in their implications for the position of the Appalachian and other trails at the time. After a primary requirement that the state hold the lands in trust forever, Baxter’s second condition was “that it shall be used for public parks, forests and recreation.” The third condition was to keep it “in its natural wild state.”

Almost from the beginning of the park, Avery was complaining about overuse, resource degradation, and hiker misbehavior on and around Katahdin and calling for greater levels of protection. It would be easy to infer in hindsight those were shots at Baxter, who legally had no management responsibility, but it should be noted that the Avery-written guides invariably included out-of-context lines about the lack (or insufficient level) of state appropriations.

Clockwise from bottom left: Baxter and Maine warden supervisor David Priest with Katahdin in background; George L. Collins, acting assistant chief of NPS Land Planning Division, Everett F. Greaton, executive secretary of the Maine Development Commission, and Avery at the 1939 conference ![]() Photo courtesy Maine State Library; A photo of Baxter published by the Portland Press Herald in 1969; Baxter and Brewer at the Maine state capitol during Brewer’s inauguration in 1925; PATC trails supervisor J. Frank Schairer and Avery at Basin Ponds the day before they went up to erect the first sign and then go south 77 miles to blaze a new A.T.

Photo courtesy Maine State Library; A photo of Baxter published by the Portland Press Herald in 1969; Baxter and Brewer at the Maine state capitol during Brewer’s inauguration in 1925; PATC trails supervisor J. Frank Schairer and Avery at Basin Ponds the day before they went up to erect the first sign and then go south 77 miles to blaze a new A.T.

Although some was through an AMC intermediary, Avery and Baxter did correspond all those years, implying that the Trail and its shelters had a fixed status in “his” park from the earliest days. Baxter’s support was occasionally explicit, although any specific written agreement for the Trail between the two men at the time of Baxter’s purchases has never surfaced. Avery would send Baxter new or older ATC publications, including his bibliography of works featuring Katahdin, of which Baxter replied he had no idea so much had been written. Baxter would ask for particular uses of his name in future guides and maps, and a line about his generosity; and Avery complied.

In 1934, a series of letters — with Baxter copied — between Avery and a U.S. Interior Department landscape architect, guiding the CCC crews in the Katahdin area, showed them working together on routes (a Hunt Trail relocation) and signs and other Trail matters. The official noted that, if the state would fund a larger park, no national park would be needed to protect Katahdin, an idea bandied about for more than 15 years.

All Avery’s 1934 “excellent” suggestions for Trail work in the park were approved by Baxter and forwarded by him to the CCC and the park commissioners, according a letter to AMC. An AMC news release from September 1934 notes that Baxter joined a “120-mile tramp over the newly constructed Appalachian Trail in Maine” for part of the journey. That month, Baxter and the landscape architect, after spending a night with Trail workers, “invited the A.M.C. to build a hut anywhere at K. and under any conditions,” according to a letter to Avery from his intermediary. In March 1935, Baxter wrote Avery directly that he and AMC “have rendered a very distinct service to the State of Maine.” He might have meant “ATC.”

Nineteen-thirty-four was the same year former Governor Brewster, Baxter’s rival, finally won a seat in the U.S. House. In March 1937 — with Avery saying in his correspondence that it was his idea and others saying it was a NPS initiative — Brewster introduced legislation to acquire Baxter State Park for the national park system.

As de facto decider-in-chief, Baxter continued to take advantage of CCC federal labor but was virulently opposed to the federal government’s taking the park from the people of Maine. Brewster inserted into the Congressional Record an argument of more than a page from Avery, stating in turn that national-park status was necessary to undo almost a decade of state neglect of Katahdin’s resources. He took a veiled shot at AMC in the process. Avery had the backing of an ATC resolution from its 1937 general meeting in Gatlinburg, Tennessee. The Portland Sunday Telegram gave Avery almost two pages to make his argument.

Five weeks before the Appalachian Trail was officially continuous from Maine to Georgia, with a two-mile Maine gap closed by the CCC, Avery speculated in a July 10, 1937, letter to MATC that he had “administer[ed] the coup de grace [to the opposition] … At least, we have stirred up old man Baxter so that he went to the mountain to see what can be done.” AMC supported Baxter. As did, unsurprisingly, the Wilderness Society — founded two years earlier by Benton MacKaye and seven of his friends, four of whom also were being steamrollered by Avery out of ATC affairs at the time. The organization’s magazine in October trashed both Katahdin the mountain and the park proposal (“the climax of absurdity”). Avery, no doubt, was apoplectic. The Brewster bill was never acted on by the full House.

A letter from Baxter to Avery courtesy ATC Archives

Dave Field’s research shows that both Avery and Baxter sought for years, in principle, to reduce the level of abuse of the park from unregulated recreation. They complained in writing to each other in 1934 about conditions at Chimney Pond (northeast of the summit), and Baxter added, “I can see that we are in accord on all of these matters, and I wish to do everything I can to help the proper development of the park area.”

After he lost the House battle in 1938, Avery complained to a reporter of “the total failure of the State to make any appropriation and the chaotic and unfortunate situation which results … Mr. Baxter is an ardent states’ rights individual. Granting his sincerity and interest, he would rather see the region wrecked than in the hands of the Federal Government.” Before and after the congressional battle and tugs of war among organizations, both complained of attacks on them and pointed to each other as the source. “One positive result of the battle…,” however, Neff writes in Katahdin, “was the recognition by the state of Maine that it could no longer neglect its responsibility to better manage the land Baxter was steadily acquiring.”

Avery remeasured the A.T. in Baxter in 1938 and published new Trail data, noting, “With the exception of the Appalachian Trail, there has been, since 1934, no maintenance work or renewal of marking of any trails in the Katahdin Region.” A year later, in 1939, implicitly at Baxter’s behind-the-scenes insistence, Maine became the only one of the fourteen Trail states to refuse to sign an “Appalachian Trailway” protection agreement initiated by Avery and his federal-agency Trail partners. (A few months later, the ATC started charging Baxter for publications it had been sending this wealthy scion gratis for almost a decade…and even noted his perceived chicanery while responding to his requests.)

Baxter State Park had no rangers until 1939 — the same year the ATC held its ninth membership meeting (of 125) at a sporting camp on Daicey Pond. Three A.T. shelters existed in the park. As that meeting proceeded, Baxter, who had tripled his purchases that year, signed in at the register at Chimney Pond on the other side of the mountain, notes Katahdin Outdoors.com, but apparently did not stay to join the ATC meeting when it ended with a special trek to Chimney Pond. Federal employees continued to work in the park.

Finally in 1939, the five-year-old Baxter State Park Commission was abolished in favor of a still-empowered Baxter Park Authority: the state attorney general, director of the Bureau of Forestry, and commissioner of inland fisheries and game. Before and after that switch, correspondence shows, the latter two commissioners regularly worked with Avery on trail-management issues. Over the next few years, shared responsibilities for Baxter park trail maintenance were defined explicitly between the state and AMC alone.

Attendees of the 1939 conference spent the second part of their meeting at Chimney Pond

![]() by Frederick F. Schuetz/ ATC Archives

by Frederick F. Schuetz/ ATC Archives

The third of three September 1944 essays on the park in The Living Wilderness, the Wilderness Society’s magazine, notes in the penultimate paragraph: “Before Mr. Baxter gave the mountain to the state, little supervision was exercised. Trails grew up as required and a few badly needed shelters were built by one organization or another…Both the Appalachian Mountain Club [under a 1941 agreement with the park authorities] and the Appalachian Trail Conference have taken over the maintenance of specified trails which together make up most of the paths on the mountain. Signs are placed at intersections and the trails are well marked.”

AMC’s maintenance role at Baxter waned following World War II. In 1981, MATC assumed a secondary role in Trail work under the spare terms of five-year cooperative agreements with the park, which sets the standards and “retains all authority for the administration of the Appalachian Trail within the boundaries of Baxter State Park.” Clearly, however, none of that Appalachian Trail activity could have happened between 1929 and 1939 without the concurrence of both Baxter and the Baxter State Park Authority and its predecessor agency.

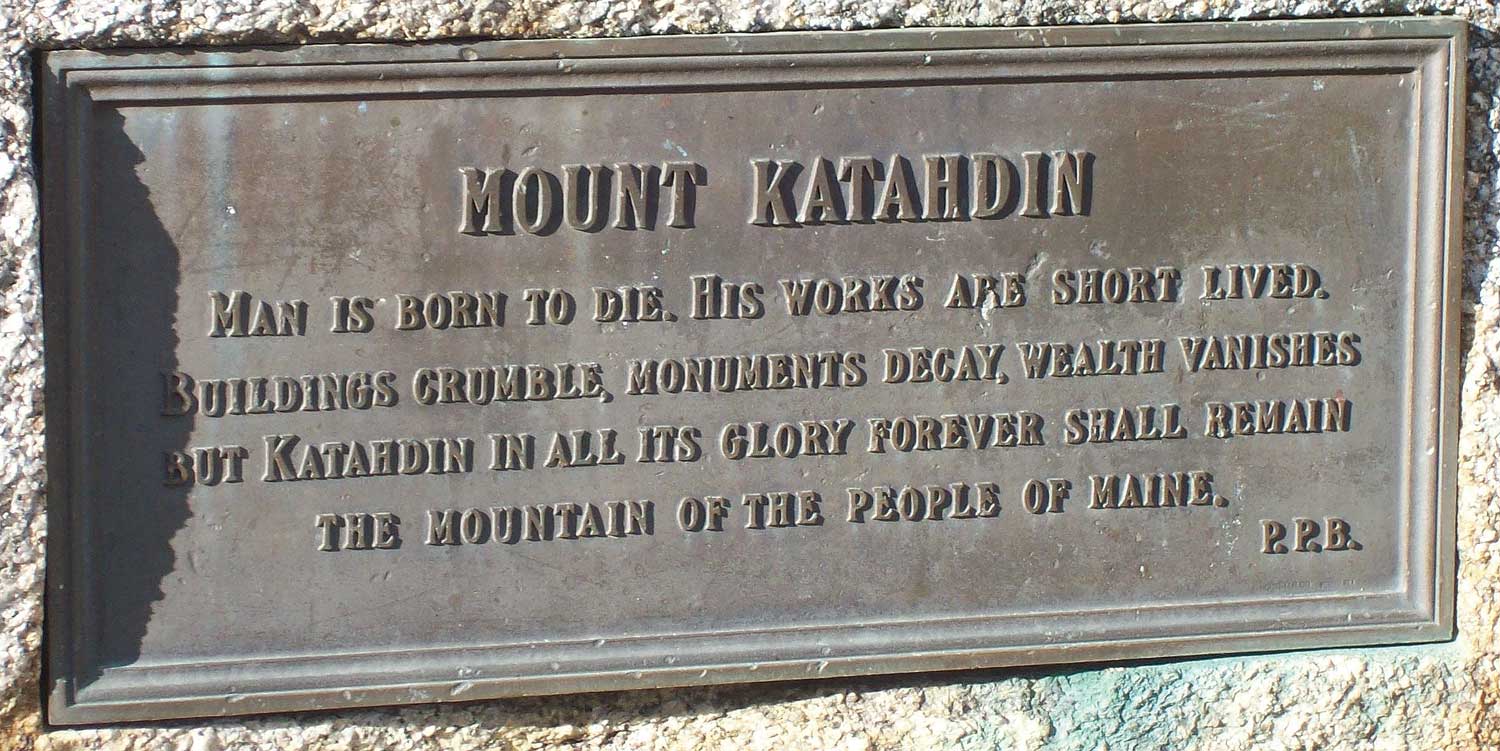

A plaque that Baxter had installed below Katahdin a few years after he started buying land to create the park

![]() courtesy Baxter State Park

courtesy Baxter State Park

Two Bowdoin and Harvard boys of different eras and upbringings, who rarely brooked any real or perceived opposition in their public lives, each saw themselves as Katahdin’s most favored suitor. One stepped into a political battle and ultimately forfeited the potential to continuing sharing with Baxter joint oversight of the Katahdin trail he so meticulously measured. Following a funeral at the family’s seaside home, after a massive heart attack in 1952, Myron Halliburton Avery was buried in a modestly marked grave back home in Lubec, his coffin covered in spruce boughs. Percival Proctor Baxter lived for another 17 years. His ashes were scattered in his namesake park, a year after Congress created the Appalachian National Scenic Trail, a unit of the national park system.