Named the 2024 Bird of the Year by the American Birding Association, the golden-winged warbler dwells in two worlds. All neotropical migratory birds nesting in North America and wintering in Latin or South America remind us that we are linked on one life-giving blue planet spinning around the sun.

The trail of a golden-winged warbler is a skyway. Shelter lies in stopovers where a bird can find trees, shrubs, and insects to eat. The destination is a nesting haven. Along the A.T., those habitats fall on high-elevation shrubby meadows feathering into deep forests. While the warblers migrate and nest all the way up the Appalachians into southern New England, the ATC focuses on improving key habitats in Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

Golden-winged warblers nesting in the United States represent 84% of the species’ global population

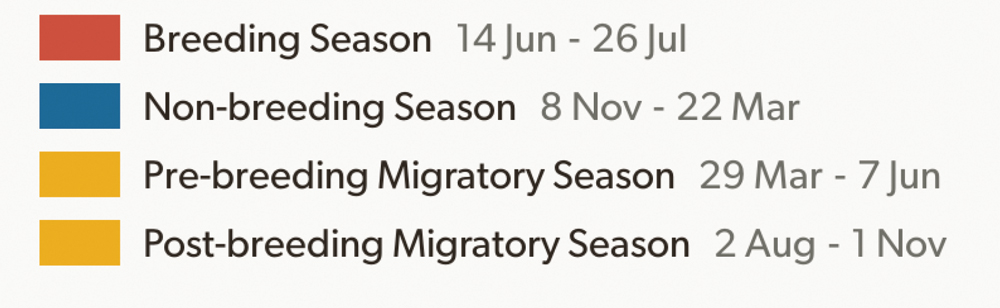

Golden-winged warblers’ migration

One tool for making a beautiful mess is a large mower called a skid steer. For anyone who has known the tedium of mowing manicured lawns, this task is far more interesting.

“It’s not like mowing your lawn,” he explains. “You have to avoid the milkweed, the monarda, the goldenrod, and some of the blackberries. We’re creating a light touch of a mosaic and mowing without a pattern.”

The patchy mowing reflects a major shift from a decade ago when the ATC and the U.S. Forest Service (where the Trail passes through national forests) managed open meadows primarily for views.

“While well intended, A.T. managers then mowed everything in the openings to make people feel like they were in ‘Little House on the Prairie,’” McBane says. “And they often mowed in May, June, and July, causing significant impact to biodiversity.”

Butterflies at risk of extinction benefit too. Monarchs lay eggs on milkweed plants that are the sole hosts of caterpillars. The Diana fritillary, a showy big butterfly of the southern Appalachian Mountains, relies on edges and openings among moist mountain forests and only breeds if the wooded margin is intact.

“Now, the Tilson tract is the biggest hotbed of golden-wings in the George Washington National Forest,” McBane says.

Each nesting territory is about five acres — the size of a baseball field, but nothing like it in appearance. A female weaves her nest on the stems of a goldenrod or a blackberry bush and far down at the base for concealment. Each delicate cup holds three to six eggs.

Once the chicks hatch, they need plentiful protein. Native trees hosting abundant caterpillars play a key role. Parents fly back and forth from the nest with insects. The male also likes to sing and defend a territory from a nearby tree. But not just one tree in the opening will do. The best scenario is five to 15 trees per acre. When the chicks fledge, the families fly into adjacent mature forests for food and shelter.

He’s surprised that the higher-elevation meadows of the A.T. in Virginia, like Mount Rogers and Whitetop, lack golden-winged warblers, because the conditions seem right for them. McBane’s work to enhance habitat in some of the highlands is helping other wildlife like the Appalachian cottontail and overall diversity. He hopes one day the golden-wings will find a nesting haven there, too.

There’s another reason to pay close attention to the highest elevations on the A.T. As climate change warms the planet, many species are moving up in elevation or north to find cooler refugia. The golden-winged warbler’s range has already shifted northward in recent decades. Those mountainous habitats may also lessen the chances of hybridizing with the closely related blue-winged warbler that tends to nest lower down.

Matt Drury, the ATC’s associate director of science and stewardship, focused his binoculars on the tiny bird with a dash of yellow on wings and head feathers, a black eye streak, and a chickadee-like black bib. Yes, this golden-winged warbler was decidedly belting out a blue-winged warbler tune.

Baffled, Drury turned to Avery Young, a biological science technician with the Pisgah National Forest. They stared and listened. This was not how they imagined the start of their field day recording birds and hoping to hear and see golden-winged warblers.

The two warbler species are so closely related they can mate and produce offspring, known as Brewster’s warblers. This causes genetic dilution of both species — and is particularly problematic given the golden-wings’ diminished population size.

Later that day, Young found another golden-winged warbler singing the expected song in a 13-acre area between Max Patch and Buckeye ridge, where the ATC had recently completed a tree thinning to maintain views and improve the warblers’ habitat. That sighting was welcome news. Biologists estimate only 1,000 golden-winged warblers make it to western North Carolina, with fewer each year.

“Those are some of the thorniest, meanest blackberry I know,” Drury says. “That’s the best closure possible.”

Mowing every two to five years is about right, Drury said, along with other enhancements conducted in a partnership with the Pisgah National Forest. While Max Patch is a focus, he’s also giving warbler habitat a boost at other places along the Trail including Hump Mountain and the Upper Laurel Fork area of Tennessee.

Imagine this scene: First light enters the Knot Maul Branch Shelter in Virginia where a couple backpackers stir in their sleeping bags, wakened by the dawn chorus. Among the serenading birds is a golden-winged warbler heralding the day with the right song on a day where everything will go… just right.