I gained my first A.T. kinsman, not on the Trail itself, but in northern Virginia. In January 1979, an outdoor shop hosted a presentation by Ed Garvey, author of Appalachian Hiker: Adventure of a Lifetime, widely regarded at the time as the authoritative text for aspiring A.T. thru-hikers. Garvey described his early-1970s end-to-end trek and dispensed a wealth of tips. At the end of his talk, he asked the fateful question: “Is anyone planning to hike the Trail this spring?”

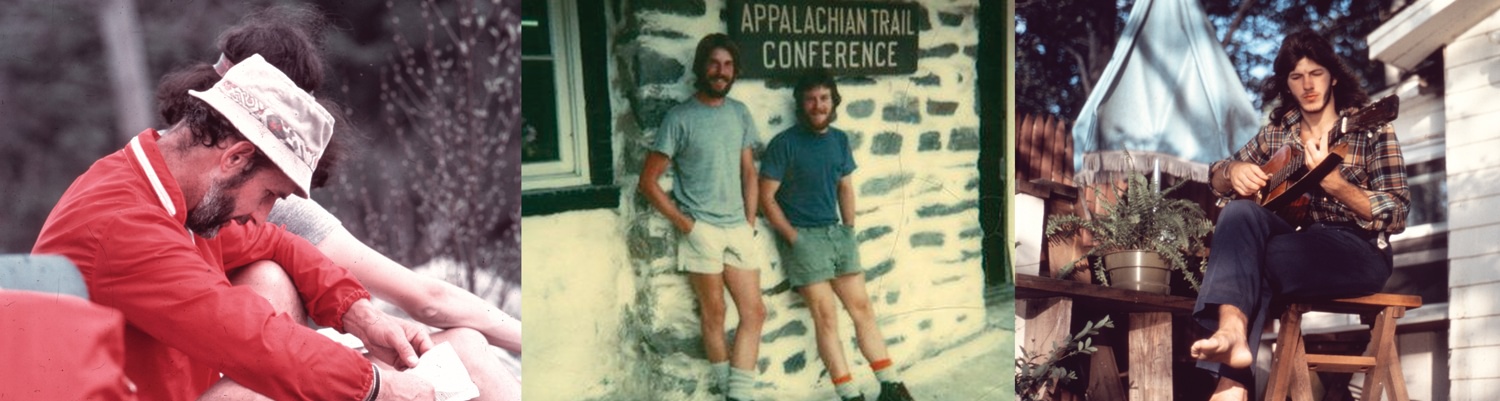

Two raised hands appeared. One of them was mine; the other belonged to a lean, bearded, sandy-haired man about my age of twenty-three. Within a half-hour, I was seated in a local bar across the table from Dan Howe. As we discussed our plans for the spring, we each surreptitiously gauged the suitability of the other as a long-distance hiking companion.

In that regard, Dan was an immediate shoo-in. His years at the University of Virginia, set in the shadow of the Shenandoah Mountains, had allowed him to hone his considerable backpacking skills and bestowed on him an academic degree in planning. Both would prove valuable on the Trail, particularly for someone like me who was profoundly deficient in both regards. After a few rounds of beer, we agreed that we would begin the Trail together and assess the partnership as we progressed north. A “shakedown” hike a month before our planned departure proved disastrous, at least for me. During two days of rain, my flapping poncho did little to keep me dry, and my new boots rubbed my heels to blisters. Meanwhile, Dan seemed to be thriving. I recall being beset by misery at our campsite while noting Dan’s entirely antithetical response; he stood stark naked under a teeming waterfall, blissfully sipping bourbon from a plastic bottle.

April 21, our day of reckoning, arrived, and I tentatively shouldered a backpack that burgeoned with useless items I would soon send home. But the pack itself proved far less burdensome than the emotional heft of what I was about to undertake — a 2,100-mile journey on foot. As noted, Dan’s woods-sense far exceeded my own, and over the coming months, he would impart vital lessons on wilderness travel and backcountry living. And Dan, the planner, would soon emerge as field marshal, always measuring the months against the remaining miles and ensuring that we hewed to our tightly regimented schedule. Were it not for Dan, I suspect that Katahdin would have remained an elusive goal and one that I would never reach. But, by that September, when we embraced each other atop Baxter Peak, Dan and I had forged a bond that would endure no matter how much time and distance separated us. To this day, he remains at the very top of a short list of my dearest friends.

Dan and I welcomed our third family member, Nick Gelesko, the “Michigan Granddad,” over a vegetarian meal at The Inn (now Sunnybank) in Hot Springs, North Carolina. Nick, then 57 and a veteran of World War II, was closer to the age of our parents, which initially created a bit of an intergenerational divide. But, the A.T. is a great social equalizer, and, after a few open conversations around our evening campfires, we would come to value Nick’s life experience and wise perspectives. I immediately detected in him an irrepressible charisma — an attribute that would make him an endearing companion and prove remarkably resourceful in earning favored treatment from the locals we encountered along the way.

Nick’s nearly always-successful solicitation of acts of kindness — round-trip rides from trailheads into town, offerings of food and drink, permission to stay overnight in guest bedrooms — became the stuff of legend among members of the Trail community. For a time, we struggled with what to call Nick Gelesko’s magical process. Finally, we fixed on a term derived from his last name. Gel es´ko ing: gerund, use of tact and persuasion by A.T. hikers to incline townsfolk to provide goods and services free of charge (also commonly known among contemporary thru-hikers as “yogi’ing”). And, we applied the term, in verb form, in the following ways:

“Where did you get that sandwich?”

“I Geleskoed it from some picnickers a few miles back.”

“How did you get into town?”

“I Geleskoed a ride from a nice couple returning from church.”

Far from feeling exploited, the Trail-town locals always seemed to delight in helping us out.

By then, we had welcomed the fourth member of our primary Trail family. When we had encountered twenty-year-old Paul Dillon, a lanky former competitive downhill skier, in Pennsylvania, he was making his third attempt on the A.T. This time he would go on to finish. Paul, a New Hampshire native with shoulder-length brown hair bound by a bandanna tied pirate-style, was easy-going to a fault, and he seemed inclined to abide whatever nature threw his way and try to make the best of it. For Paul, miles did not measure linear distance so much as they traced units of experience. He fully embraced the joy, the beauty, and the wisdom lurking in the wilderness, and he translated those elements into verses he composed along the way and shared with the rest of us over our evening campfires.

I didn’t fully appreciate just how graceful Paul was on his feet until we had reached the White Mountains of New Hampshire, with their open, treeless ridges. Dan and I had arrived at Lakes of the Clouds Hut, nestled beneath the summit of Mount Washington, and after dumping our packs, we climbed to the top of nearby Mount Monroe. From our perch a couple hundred feet above the Trail, we watched hikers wend their way along the rocky pathway. Some surged ahead like jackrabbits, others clumped along, and a few labored like arthritic octogenarians. Then we fixed on a lone hiker, who, unlike the others, seemed to flow along the open ridge as fluidly as a brook coursing its way over the boulders of a streambed. It wasn’t until he reached the base of the mountain that we recognized the familiar green backpack and red bandanna as belonging to our own poet laureate, Paul.

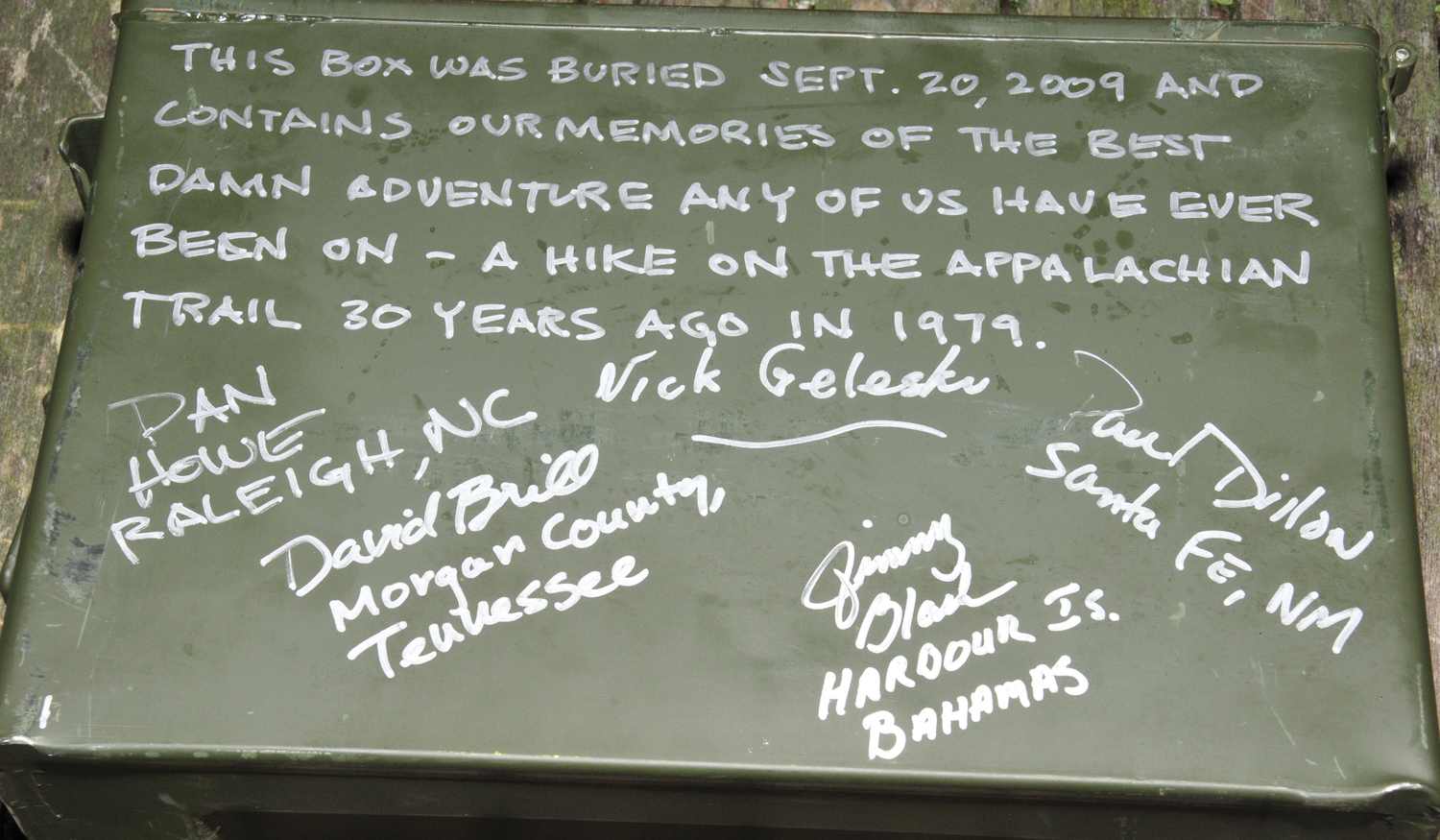

While the four of us constituted our core Trail family, over the course of the summer, we acquired numerous “cousins” — friends whose journeys intersected with ours multiple times along our collective march toward Maine. Messages conveyed through shelter journals allowed us to reunite for the Trail’s final few miles, and on September 27 — Paul’s twenty-first birthday — seventeen of us converged on Baxter Peak and posed for a triumphant group photo.

Following completion of our thru-hikes, Dan, Nick, Paul, and I returned to our homes, resumed our lives, and drifted apart for the better part of two decades. But in 1999, National Geographic Traveler generously agreed to fund a twenty-year reunion.

The plan was to stand atop Katahdin twenty years from the day of our first ascent. Nick, who was then seventy-seven, was a big question mark in terms of scaling what remains generally known as the A.T.’s toughest mountain, but with Dan’s constant encouragement — and the occasional shove on Nick’s bony butt along the steeper sections of the climb — we all reached the summit by early afternoon.

In the months before the fortieth anniversary of our hike, Dan and I had reached out to the individuals captured in the original 1979 summit photo, and, in September 2019, eight of us converged on Millinocket, Maine. Gathered with us at the Big Moose Inn were Robin Phillips, a professional photographer, and his brother Paul, a medical doctor, both based in Lakeland, Florida; Jeff Hammons, a teacher of gifted students on the Navajo Nation in Shiprock, New Mexico; Cindy Taylor-Miller, a banker and former Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) guidebook editor who resides proximate to the A.T. in Wallingford, Vermont; Jim Schaffrick, a woodworker living in Litchfield, Connecticut; and Gary Owen, a retired engineer whose home is in Knoxville, Tennessee. Paul, a singer-songwriter, and Dan, recently retired assistant city manager for Raleigh, North Carolina (now in his fourth year on the ATC board of directors), were there, too, but one face was conspicuously absent. Our beloved companion Nick had reached the age of 94 before passing away in 2016. In his remembrance, we would carry a portrait of him to Katahdin’s summit.

As before, our time on Baxter Peak inspired a range of powerful emotions. Among them, for me, was the recognition that we no longer enjoyed the buoyancy of youth and, with it, came the realization that this visit to Katahdin’s summit might be our last. There wasn’t so much sadness in the thought as gratitude for affording us the chance to gather, yet again, atop a mountain that looms as large in our collective memories as it does in the topography of north-central Maine.

The closing paragraph of my reunion article for National Geographic Traveler rings as true today as when I crafted it more than twenty years ago and says much about how I continue to regard the people who were central to my A.T. experience:

“It was on the Trail, in 1979, that I began to grasp that the endless cycling of seasons — the perfect metaphor for life — is meant to bring us around, to guide us home. Which is why I returned to Maine, to gather with cherished friends who are, and always will be, part of my family and, for a time, to reduce the complexity of my life to the simplicity of a white blaze and dirt path headed north.”

Brill has published five nonfiction books. His first, As Far as the Eye Can See: Reflections of an Appalachian Trail Hiker, is a collection of essays based on his 2,100-mile trek of the A.T. in 1979. In 2020, the book was released in its fifth (thirtieth anniversary) edition and eighth printing. The new edition contains a new preface (on the fortieth reunion) and three bonus chapters. His most recent book, Into the Mist: Tales of Death and Disaster, Mishaps and Misdeeds, Misfortune and Mayhem in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, published in 2017, is now in its fourth printing.

In 1981, Brill and three other former A.T. end-to-enders hiked the then-proposed Pacific Northwest Trail, which is now part of the national scenic trail system. He has climbed 14,400-foot Mount Rainier twice and, in 2001, reached Denali’s 20,320-foot summit. Brill, his wife, Belinda, their dog, Zebulon, and their cat, Tater Tot, live in a cabin on Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau.