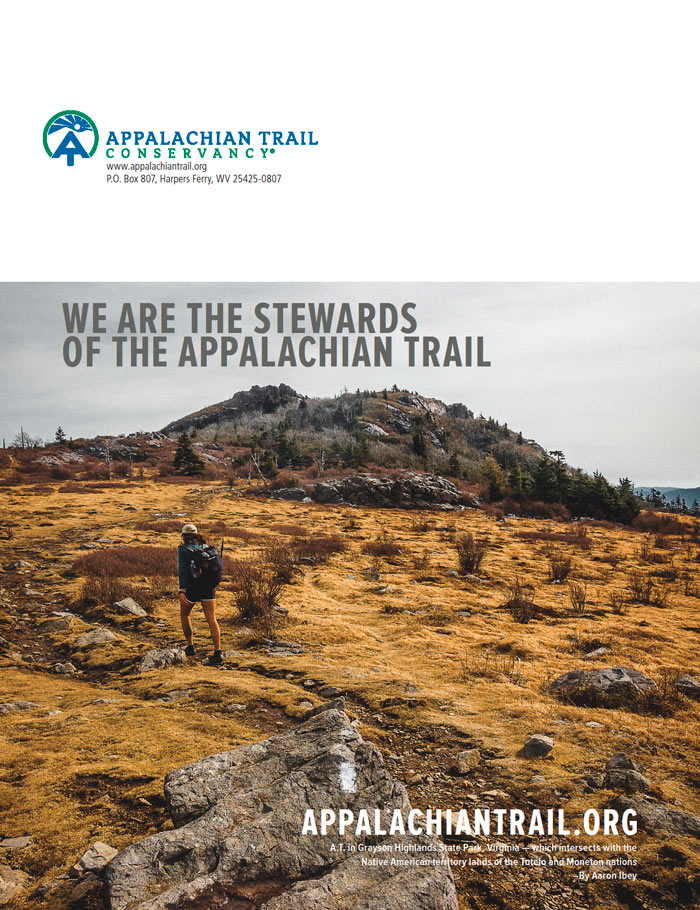

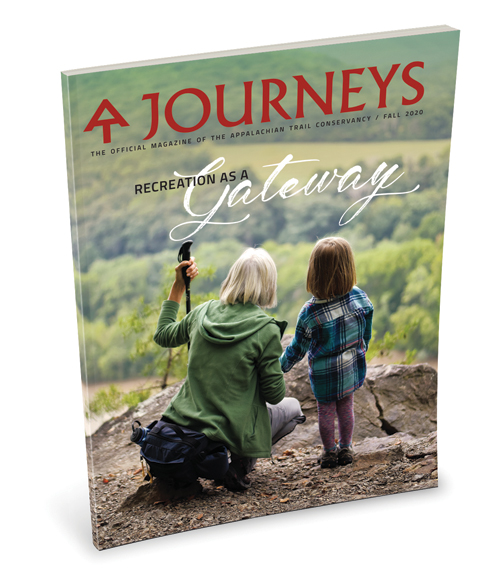

ON THE COVER

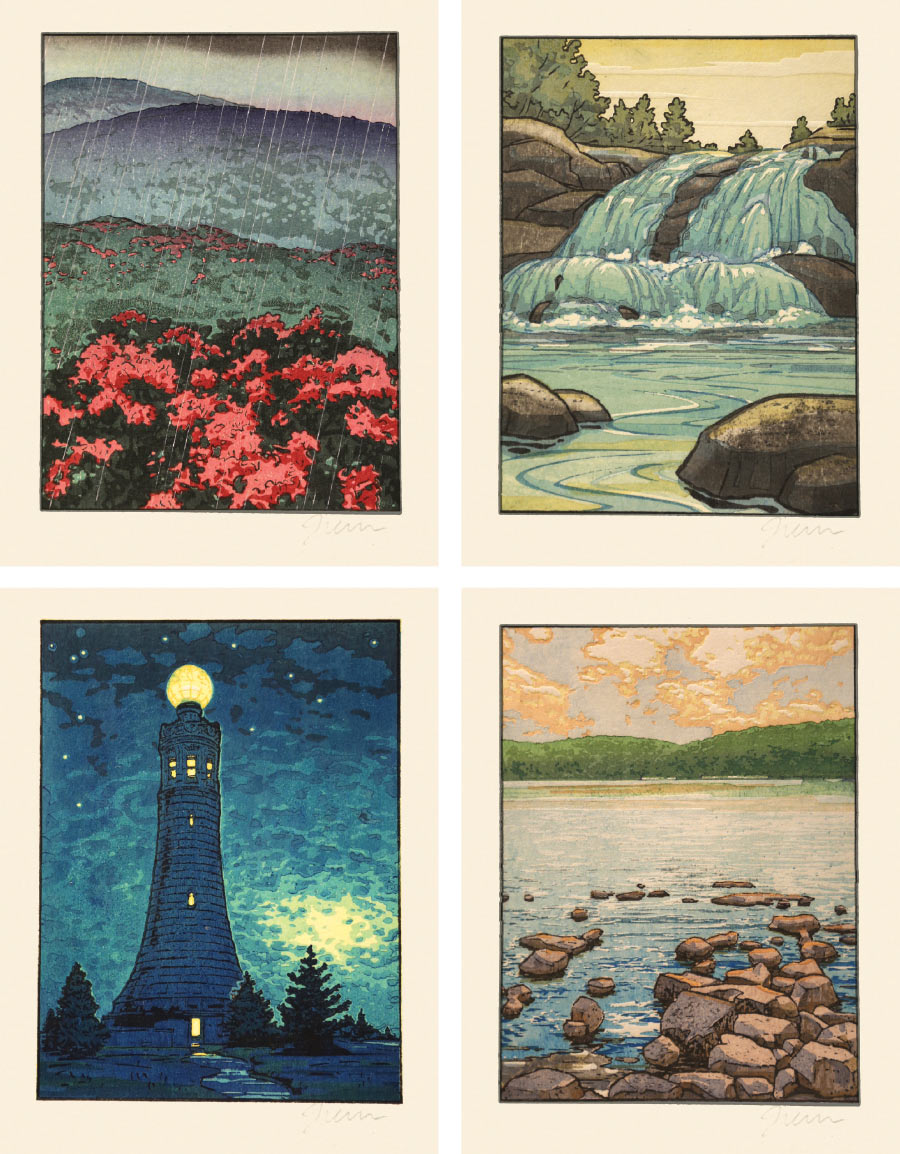

Appalachian Trail near Mount Rogers, Virginia — which intersects with the Native American territory lands of the Moneton Nation. The A.T. runs through 22 Native Nations’ traditional territories and holds an abundant amount of Indigenous history. Photo by Jeffrey Stoner

Above: Rocky Fork Creek along the A.T. corridor in Lamar Alexander Rocky Fork State Park, Tennessee/North Carolina intersects with the Native American territory lands of the S’atsoyaha Nation.

Photo by Jerry Greer

ON THE COVER

Appalachian Trail near Mount Rogers, Virginia — which intersects with the Native American territory lands of the Moneton Nation. The A.T. runs through 22 Native Nations’ traditional territories and holds an abundant amount of Indigenous history. Photo by Jeffrey Stoner

Above: Rocky Fork Creek along the A.T. corridor in Lamar Alexander Rocky Fork State Park, Tennessee/North Carolina intersects with the Native American territory lands of the S’atsoyaha Nation.

Photo by Jerry Greer

Sandra Marra / President & CEO

Nicole Prorock / Chief Financial Officer

Shalin Desai / Vice President of Advancement

Laura Belleville / Vice President of Conservation & Trail Programs

Cherie A. Nikosey / Vice President of Administration

Brian B. King / Publisher & Archivist

Wendy K. Probst / Editor in Chief

Traci Anfuso-Young / Art Director / Designer

Jordan Bowman / Director of Communications

Laurie Potteiger / Information Services Manager

Brittany Jennings / Proofreader

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s mission is to protect, manage, and advocate for the Appalachian National Scenic Trail.

Colin Beasley / Chair

Robert Hutchinson / Vice Chair

Edward R. Guyot / Secretary

Jim LaTorre / Treasurer

Daniel A. Howe / Stewardship Council Chair

Grant Davies

Norman P. Findley

Thomas L. Gregg

John Knapp, Jr.

Ann Heilman Murphy

Colleen Peterson

Eboni Preston

Nathan G. Rogers

Rubén Rosales

Patricia D. Shannon

Rajinder (Raj) Singh

Ambreen Tariq

Hon. Stephanie Martz

Diana Christopulos

Jim Fetig

Lisa Koteen Gerchick

Mark Kent

R. Michael Leonard

Robert Rich

Hon. C. Stewart Verdery, Jr.

For membership questions or to become a member, call: (304) 885-0460

![]()

[email protected]

A.T. Journeys is published four times per year. Advertising revenues directly support the publication and production of the magazine, and help meet Appalachian Trail Conservancy objectives. For more information and advertising rates, visit: appalachiantrail.org/atjadvertising

MISSION

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s mission is to protect, manage, and advocate for the Appalachian National Scenic Trail.

Colin Beasley / Chair

Robert Hutchinson / Vice Chair

Edward R. Guyot / Secretary

Jim LaTorre / Treasurer

Daniel A. Howe / Stewardship Council Chair

Grant Davies

Norman P. Findley

Thomas L. Gregg

John Knapp, Jr.

Ann Heilman Murphy

Colleen Peterson

Eboni Preston

Nathan G. Rogers

Rubén Rosales

Patricia D. Shannon

Rajinder (Raj) Singh

Ambreen Tariq

Hon. Stephanie Martz

Diana Christopulos

Jim Fetig

Lisa Koteen Gerchick

Mark Kent

R. Michael Leonard

Robert Rich

Hon. C. Stewart Verdery, Jr.

A.T. Journeys is published on Somerset matte paper manufactured by Sappi North America mills and distributors that follow responsible forestry practices. It is printed with Soy Seal certified ink in the U.S.A. by Sheridan NH in Hanover, New Hampshire.

A.T. Journeys ( ISSN 1556-2751) is published quarterly for $15 a year by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, 799 Washington Street, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425, (304) 535-6331. Bulk-rate postage paid at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and other offices. Postmaster: Send change-of-address Form 3575 to A.T. Journeys, P.O. Box 807, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425.

Trey Adcock

Trey Adcock (ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ, enrolled Cherokee Nation), PhD, is an associate professor of Interdisciplinary Studies and the director of American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the University of North Carolina Asheville. In 2013, Trey participated in the Trail for Every Classroom program hosted by the ATC and has hiked multiple portions of the southern section of the Appalachian Trail with friends and family. In 2018, Trey was named one of seven national Public Engagement Fellows by the Whiting Foundation for his oral history work in the TutiYi “Snowbird” Cherokee Community. “I wanted to share my story and understanding of land acknowledgement outside of the general bland academic statements that have become the recent fad,” he says. “The Trail means so much to so many people I thought it was important to provide a perspective that not everyone knows or even thinks about — the daily act of land acknowledgement for Indigenous peoples.” (page 16)

Shilletha Curtis was born in Newark, New Jersey and spent much of her time growing up in Morristown and down by the shore. She received her Bachelor’s in Social Work from Rutgers University in 2014. Before that, she spent a summer in China honing her Mandarin skills followed by an internship at an orphanage in Romania. Helping people has always been her passion but she found that she had a profound love for animals and eventually the outdoors. She trained and then worked as a veterinary technician in Austin, Texas and practiced for two years; but she realized that there was more to life than working a nine-to-five when she lost her job due to the coronavirus pandemic in 2020.

Shilletha discovered the Trail last year while hiking with her girlfriend and caught the A.T. bug since then. With a new outlook on life, she has been preparing for an A.T. thru-hike this winter (page 26). “I want to make the A.T. more accessible to the Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) community and address inequalities and racism within the hiking community,” she says. After the A.T., Shilletha will tackle the second leg of her plan to hike the “Triple Crown” on the Pacific Crest Trail and see where her hiking career takes her.

Mills Kelly is a professor of history at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. He is currently writing a history of the Trail and has just completed a shorter book titled Virginia’s Lost Appalachian Trail, about the original route the Trail took between Roanoke and Damascus, that he hopes will be published in 2021. “I first hiked on the A.T. in the early 1970s and it seems like the Trail has been part of my life ever since,” he says. “While researching my book, I kept looking for sources that spoke directly to the role that race has played in the history of the Trail. The more I looked, the more frustrated I became about the almost total absence of such sources. I wrote an article about the A.T. and race (page 24) to try to shed some light on what is truly the most under-appreciated and under-discussed part of the Trail’s history.”

Fred Tutman is a grassroots community advocate for clean water in Maryland’s longest and deepest intrastate waterway and holds the title of Patuxent Riverkeeper, which is also the name of a nonprofit organization that he founded in 2004. Some of the lessons learned on the Appalachian Trail — as both a hiker and Potomac Appalachian Trail Club member — have inspired his work on water trails as well.

Prior to riverkeeping, Fred spent over 25 years working as a media producer and consultant on telecommunications assignments on four continents, including a stint covering the Falkland War in Argentina for the BBC and managing a Ford Foundation funded project to help African traditional healers tell their stories to the world.

Currently, Fred splits his time between Maryland and North Carolina where he maintains busy blacksmith forges in both places. He is the recipient of numerous regional and state awards for his environmental work, is the longest serving waterkeeper in the Chesapeake Bay region, and the only African-American waterkeeper in the nation. He lives and works on an active farm located near the Patuxent River that has been his family’s ancestral home for nearly a century. “My aim is to pursue justice for both people and the planet,” he says. “And to also encourage others to experience Mother Nature and forge a personal compact to protect her.” (page 54)

President’s Letter

It is this ability to recognize that we exist on a continuum that defines our human consciousness.

Lancaster, Ohio

Greensboro, North Carolina

A.T.

and

Race

I have read my way through the archives of almost every Trail club and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) and despite all my searching, I found exactly one letter among the thousands of pre-2000 documents I have examined that spoke to the issues of race and civil rights. That one letter lives in the archive of the Smoky Mountains Hiking Club in Knoxville, Tennessee.

the Trail

the Trail

In the silence of the unknown, my memory recalled the time that my girlfriend and I had found a trail alongside the road at Harriman State Park in New York last April. We eagerly jumped out of my old silver Nissan Sentra and headed into the shelter of the trees. As we trekked along, we were approached by an older man who greeted us promptly and proceeded to tell us, “You know right behind me is the Appalachian Trail. It runs all the way from Georgia to Maine and if you continue up the hill you can get to it. Have you ever been out here before?”

Latinxhikers began as an Instagram account where Adriana Garcia, co-founder, and I would share personal experiences of being out on the trails. We wanted to create a space where we could share our stories as two Latinx women and provide advice for other Latinxs to go outdoors. I wasn’t always what one would typically consider “outdoorsy.” I am a first-generation daughter of two immigrants from Ecuador. Leisure time and family vacations were few and far between for us. This meant our vacations were usually staycations. We would do pig roasts at the lake or throw big outside parties with a lot of food. This was our way of being outdoorsy, and a lot of the Latinx community resonates with that version. It wasn’t until 2016 – after I unexpectedly summited 17,000-foot Vinicunca, Rainbow Mountain in Peru – that I started hiking. I say unexpected because I honestly didn’t know what I was signing up for. The guide told us to “just wear comfortable shoes.” It was one of the hardest hikes I’ve ever done. After doing that, I felt like I could do anything. I switched up my way of travel and started visiting as many national parks as possible.

Trail Stories

–By Christian Peterson

–By Christian Peterson

AS THE PANDEMIC TOOK HOLD OF THE WORLD, group hikes and travel to hiking destinations became less safe and so the call of the trails increasingly uncertain. But the urge to get outside transformed into a constant craving. Eventually, as we all donned masks and dug in for the long haul, I headed to my Great Grandad’s farm — the best place available for me to isolate. My family’s status where I live is rare in Black communities. The U.S. Department of Agriculture statistics tell us that less than one percent of the rural land in America is owned by people of color. My family is among that lowly statistic, having the rare achievement of inhabiting a Centennial farm — one that has been in continual existence in the same family for at least 100 years. We are now “Indigenous” here. But local legends tell us that we acquired our permanent home because of a hex placed by an innocent man who had been hung from a tree like strange fruit on this very land. That same tree still stands in my front yard today. The story goes that in the early 1900s, a Black man could still be hung and lynched from a tree, and White people would chip in appreciative donations for a particularly “good” hanging. The legend says that the last Black man hung from that tree put a hex on his executioners who then encountered a series of bad breaks — including the loss of the farm. Eventually, my Great Grandfather acquired title to that once-failing and defunct farm in Prince George’s County, Maryland — not far from the Appalachian Trail — a favorite and frequent hiking spot of mine.