Centennial

Issue

-

FEATURES

-

A look at the Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s first one hundred years.

-

From copper markers nailed to trees to the familiar white blazes, official signs for navigating the Appalachian Trail have evolved alongside the ATC.

-

The ATC embodies its name, and its mission, through conservation efforts to protect the Trail.

-

As bears become more habituated to human presence on the A.T., hikers must be vigilant about food storage.

-

The ATC, its partners, and A.T. Clubs help protect and preserve the A.T. and the Trail experience through the Cooperative Management System.

-

In August 2025, current and emerging leaders from A.T. Clubs gathered for the Volunteer Leadership Meeting.

-

Through partnerships, programs, visitor centers, and supportive staff and volunteers, the ATC works to create an environment in which everyone belongs on the “People’s Trail.”

Photo by Keith Clontz

Contents: The Northern Presidentials as seen from Mount Monroe in New Hampshire’s White Mountain National Forest

photo by jerry monkman

Back cover: For more about Jean Stephenson see here

Our mission is to protect, manage, and advocate for the Appalachian National Scenic Trail.

The Appalachian Trail and its landscape are always protected, resilient, and connected for all.

Sandra Marra | President & CEO

Karen Cronin | Chief Financial and Administrative Officer

Hawk Metheny | Vice President of Regional and Trail Operations

Dan Ryan | Vice President of Conservation and Government Relations

Jeri B. Ward | Chief Growth Officer

Caroline Ralston | Associate Vice President of Marketing & Communications

Genevieve Andress | Relationship Marketing and Membership Director

Karen Ang | Managing Editor

Traci Anfuso-Young | Art Director | Designer

Ann Simonelli | Director of Communications

Michelle Presley | Communications Manager

Maddy Kaniewski | Digital Marketing Specialist

A.T. Journeys is published on matte paper manufactured by Sappi North America mills and distributors that follow responsible forestry practices. It is printed with Soy Seal certified ink in the U.S.A. by Sheridan NH in Hanover, New Hampshire.

A.T. Journeys ( ISSN 1556-2751) is published by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, 799 Washington Street, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425, (304) 535-6331. Bulk-rate postage paid at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and other offices. Postmaster: Send change-of-address Form 3575 to A.T. Journeys, P.O. Box 807, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425.

- Jim LaTorre | Chair

- Gregory Merritt | Vice Chair

- Yong Lee | Secretary

- Katherine Ross | Treasurer

- Eboni Preston Goddard | Representative to Stewardship Council

- Sandra Marra | President & CEO

- Renee Alston-Maisonet

- Rich Daileader

- Grant L. Davies

- Edward R. Guyot

- Bill Holman

- Roger Klein

- Lisa Manley

- Naman Parekh

- Nathan G. Rogers

- David C. Rose

- Patricia D. Shannon

- Rajinder Singh

- Durrell Smith

- Greg Winchester

- Nicole Wooten

A.T. Journeys is published on matte paper manufactured by Sappi North America mills and distributors that follow responsible forestry practices. It is printed with Soy Seal certified ink in the U.S.A. by Sheridan NH in Hanover, New Hampshire.

A.T. Journeys ( ISSN 1556-2751) is published by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, 799 Washington Street, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425, (304) 535-6331. Bulk-rate postage paid at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and other offices. Postmaster: Send change-of-address Form 3575 to A.T. Journeys, P.O. Box 807, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425.

Photo by Benjamin Williamson

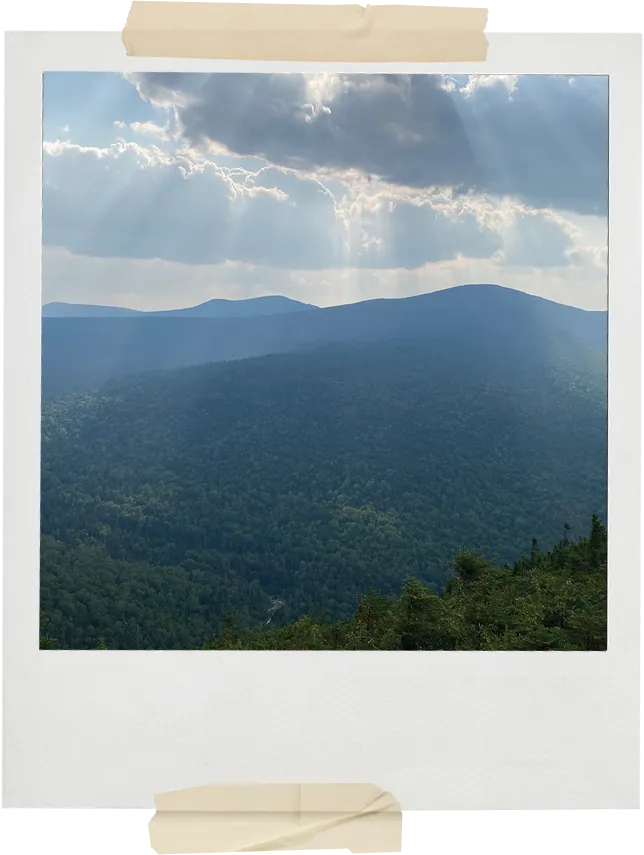

Follow the Trail across fourteen states and it becomes a passage through American wilderness and memory: the grassy bald of Max Patch in North Carolina; long-abandoned ghost towns in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley; the knife-edge ridges of Franconia Ridge in the White Mountains of New Hampshire; the backcountry of Maine’s 100-Mile Wilderness. Hikers traverse one of the world’s oldest mountain ranges and pass by battlegrounds where America fought for independence and then later, fought itself. Fred Tutman, one of the many passionate volunteers who preserve the Trail, wrote in a reflection, “Parts of it are possibly still very much like what early visitors — Daniel Boone, Johnny Appleseed, or even Harriet Tubman — saw and experienced. To me, that’s such a simple and basic thing that people take for granted as space around us is plundered, gobbled, and built on.”

Dedicated A.T. volunteers who perform essential maintenance to keep the treadway safe and sustained, build and repair shelters, bridges, and other structures, remove invasive species, and more.

20 elected members volunteer on the ATC Board of Directors

2,190+ Miles of Treadway from Georgia to Maine

Members who support the ATC’s mission to protect, manage and advocate for the A.T.

A.T. Clubs throughout 14 states

ATC Board of Directors

Throughout her work with the NPS and National Parks Conservation Association, she has seen time and again that volunteers are the backbone of public land stewardship.

“The Appalachian Trail represents something much larger than the miles it covers — it is an example of what can be accomplished through collaboration, dedication, and a shared love of the outdoors,” Waldbuesser said. “I am honored to lead the Conservancy at this pivotal moment and work with our staff, partners, volunteers, and communities to ensure the Trail continues to inspire and connect future generations.”

Most recently, Cinda served as Deputy Regional Director for the National Park Service’s Northeast Region, providing executive leadership for national park units across 1.5 million acres from Maine to Virginia. In that role, she supported 22 park superintendents with park operations and strategic communication — among those managing the Appalachian National Scenic Trail, Shenandoah National Park, and Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. She has hiked parts of the A.T. in Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey.

To allow time for knowledge transfer, strategic alignment, and continuity in leadership through the end of the ATC’s centennial year, Cinda will start as incoming president and CEO on November 17, 2025, and work closely with the ATC’s current president and CEO, Sandra Marra, until her planned retirement at the end of this year.

“We are very pleased to be welcoming Cinda to the ATC,” said Greg Merritt, vice chair of the ATC’s board of directors and chair of the ATC’s CEO search and transition committee. “Her expertise in collaborating with broad coalitions of partners and stakeholders, securing legislative and philanthropic support, and strengthening protection for national treasures like the Appalachian Trail will help us achieve our ultimate vision — for the A.T. and its landscape to remain protected, resilient, and connected for all.”

Please join us as we welcome her to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and the greater A.T. family.

Artist in Residence

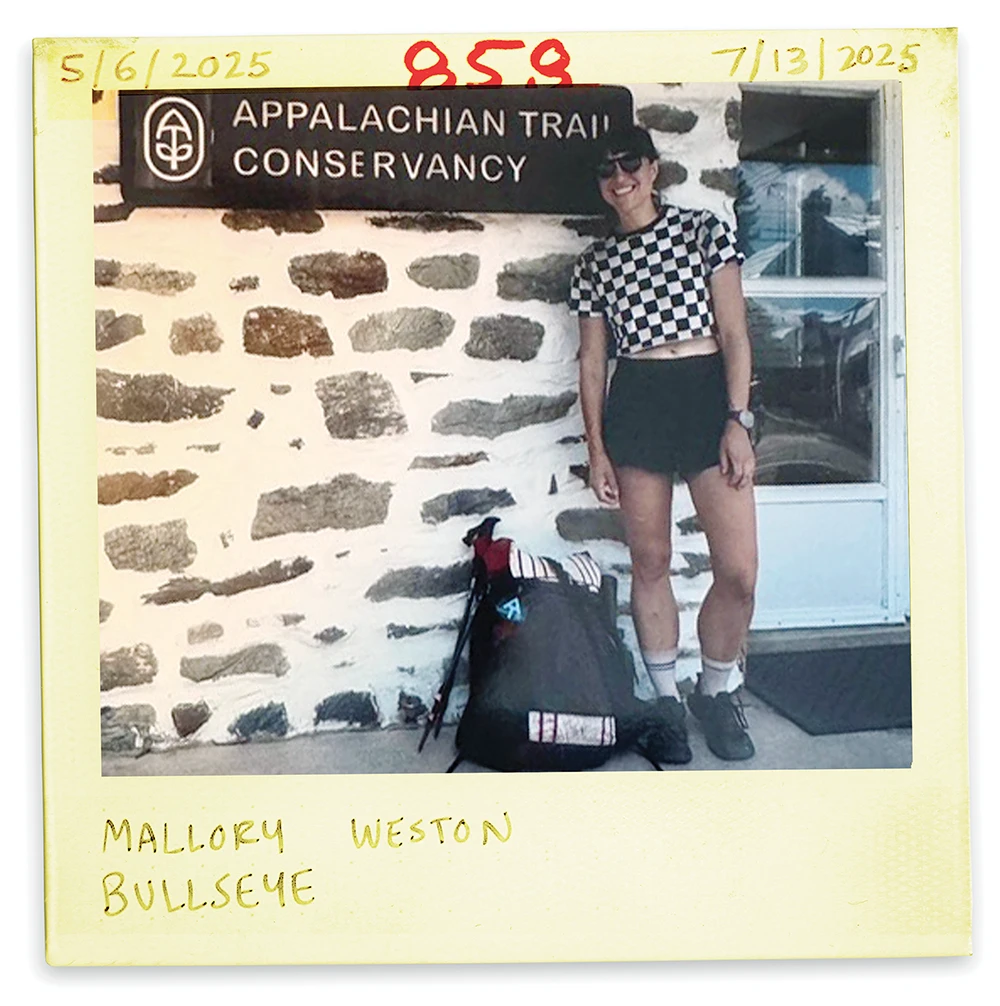

Photos courtesy of Mallory Weston (top) and the ATC (bottom)

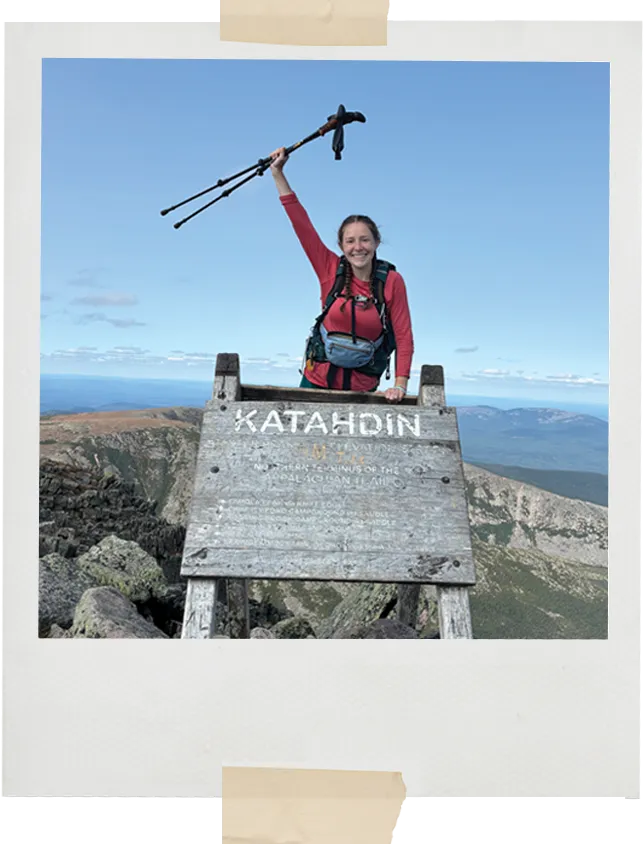

She primarily works with metal, and the inspiration she has gathered from the A.T. has been instrumental to her art. According to Weston, “Hiking the Trail as the ATC’s Artist in Residence has motivated me to be more observant of my surroundings. I’ve been actively documenting the experience through photography and journaling, wanting to remember the rich details of my hike and use them to generate artwork from the vivid text and images I’ve collected.”

After reaching Katahdin, she intends to “return to my studio in Philadelphia and create a body of work using my chosen medium of jewelry and metalsmithing. I’ve also been inspired to branch out and experiment with new artistic processes sparked by ideas developed while hiking, such as a stop-motion animation project using photographs I’ve taken since my first day on the Trail. This hike has also given me the chance to reconnect with art forms I had lost touch with, like photography and writing.”

The Artist in Residence program was created to celebrate the Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s 100th anniversary and promote the ways in which the A.T. inspires artistic expression. Looking ahead, the ATC is excited to use this Artist in Residence pilot for future planning and programs.

Photo courtesy of the ATC

Photo courtesy of the ATC

Photo courtesy of the ATC

The event brought together volunteers, land managers, and trail enthusiasts for an afternoon of educational booths, stewardship displays, and music by local favorites, The Boys. Visitors learned about the miles of trail restored since Hurricane Helene, the hundreds of hours of volunteer work contributed, and the collective effort it takes to keep the Trail alive.

A highlight of the evening was the closing reception and silent auction, which raised funds for three Appalachian Trail Community Organizations impacted by Hurricane Helene: Hot Springs, NC; Erwin, TN; and Damascus, VA. With support from the Appalachian Trail Resiliency Fund, each community organization — Rebuild Hot Springs, Rise Erwin, and Damascus Strong — will receive $1,325 to further local recovery efforts.

The celebration not only honored the Cooperative Management System but also reminded visitors that the Appalachian Trail is more than a footpath: it is a shared legacy of resilience and belonging.

Artist Anne Monger donated her time and labor to create this lovely trailscape. Monger is the founder and owner of Wallscapes Fine Arts Studio, has a BFA from Indiana University, and studied at the Chicago Art Institute. Her connection to the Trail started in childhood, though her first visit occurred in 1989. Since then, she has hiked the A.T. in 7 of the 14 states. Once she moved to the area in 2017, she often visited the Harpers Ferry Visitor Center. Finding the ATC staff and volunteers to be so welcoming, she became a volunteer in 2023.

Melanie Spencer, the supervisor of the Harpers Ferry Visitor Center, shepherded the mural proposal through the ATC, and did much of the wall prep work alongside Monger and volunteers Dottie Rust, Teresa Nankivel, Mark Bruns, Steve Huntley, and Roger Hahn. Both the artistic triumph and the volunteer efforts to create Trail Light are testimonials to the ATC’s role in channeling love for the Appalachian Trail into action.

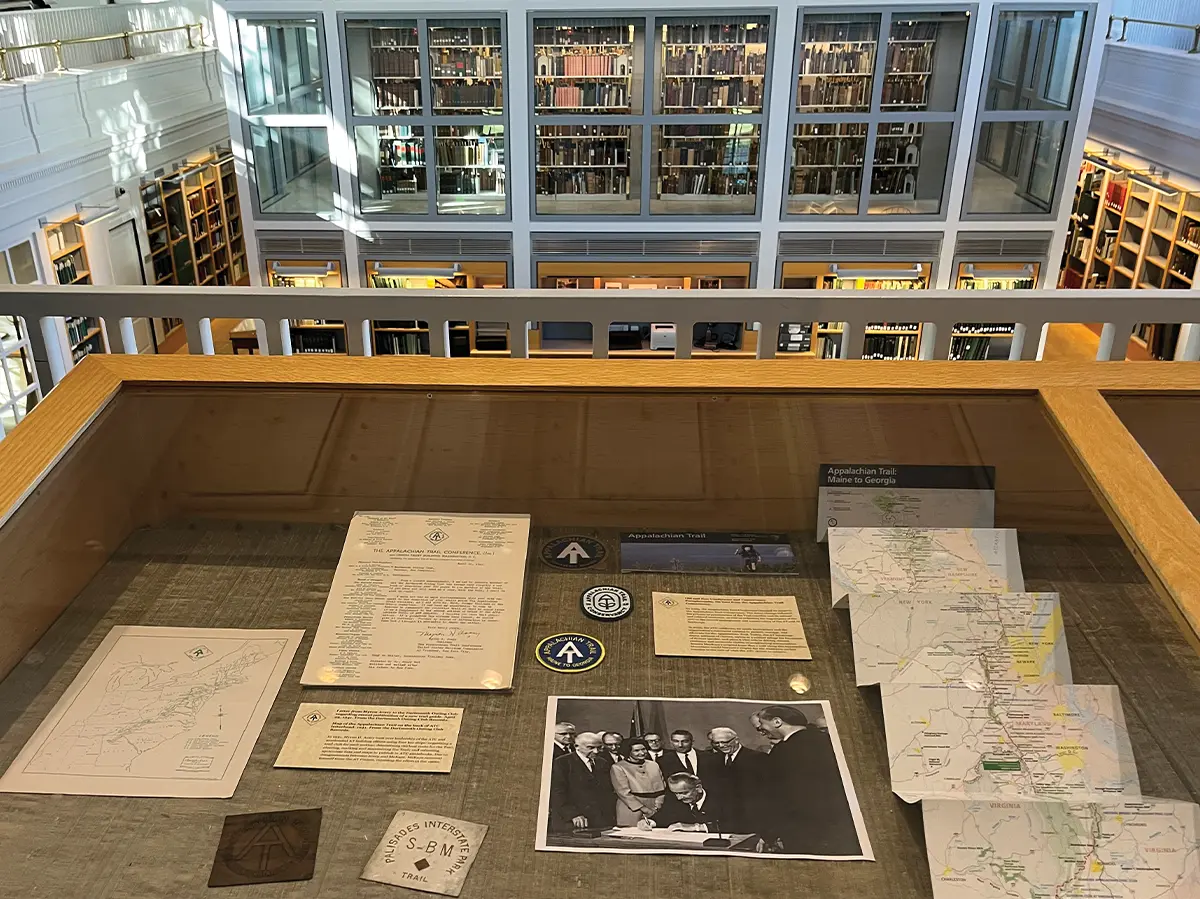

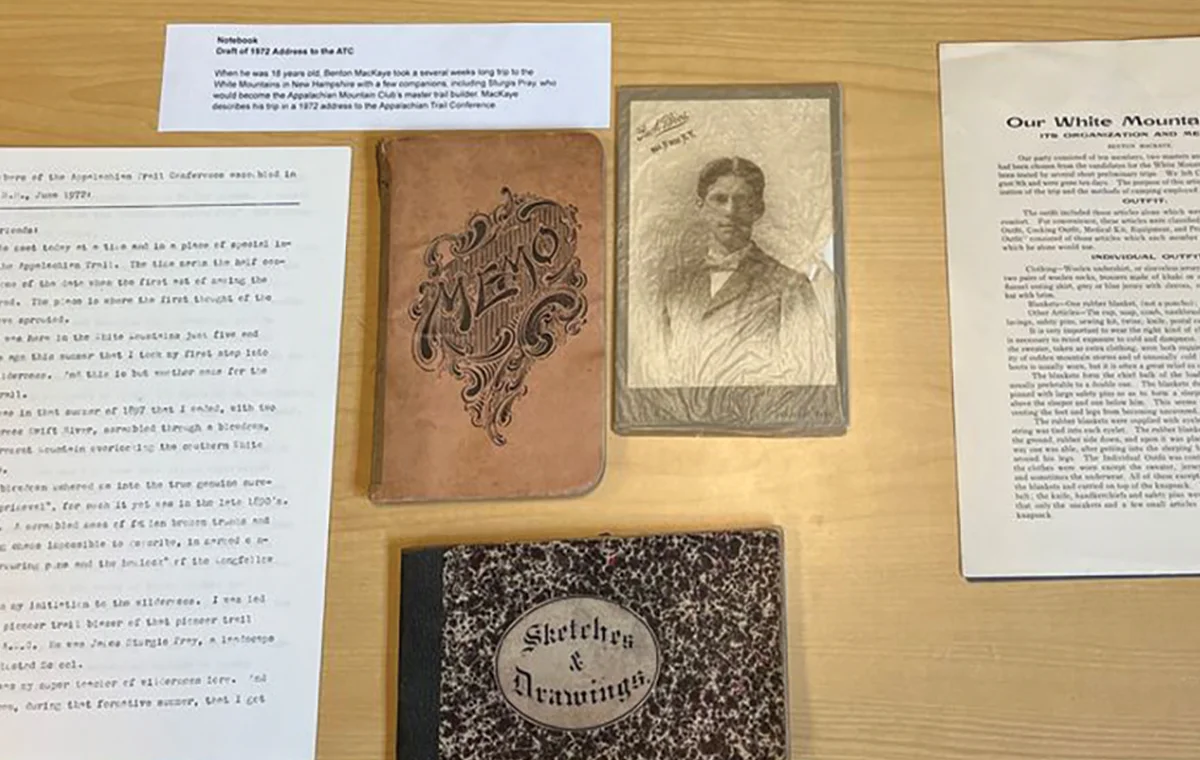

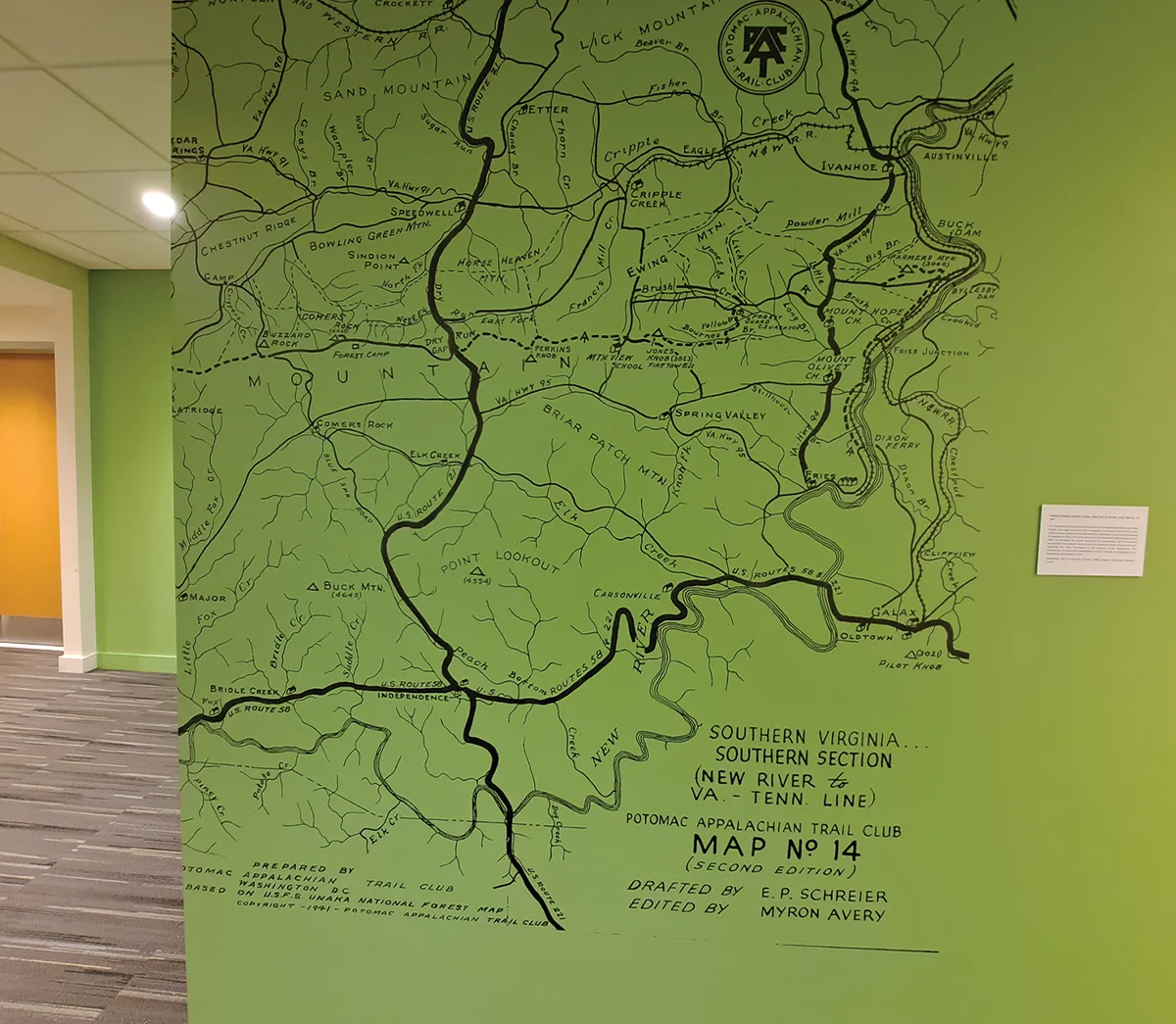

At the Rauner Library at Dartmouth, where Benton MacKaye’s papers are stored, the exhibit tells the story of the Appalachian Trail from MacKaye’s original vision to the ATC’s work now. Materials from the local A.T. club — the Dartmouth Outing Club — are also featured, along with original Trail maps, historic photographs, and MacKaye’s handwritten 1921 article where he describes his dream of a trail from Georgia to Maine. Dakota Jackson of the ATC and Morgan Swan, Special Collection Librarian for Teaching and Scholarly Engagement at Dartmouth Libraries, curated the exhibit. From Vision to Reality: The Appalachian Trail from Then to Now will be on display through December 2025.

The Special Collections Research Center at George Mason University is home to the ATC’s complete archival collections — over 700 boxes worth of materials ranging from trail management documents to photographs of Myron Avery with his iconic measuring wheel. The exhibit, titled Trail Blazing: Connecting and Keeping the Appalachian Trail focuses on showcasing the breadth of the collection and how scholars from around the world use the ATC archives for teaching, learning, and research. It will be on view through February 2026.

The Appalachian Trail is an extremely complex entity, relying on powerful but often underappreciated statutory support. The “organic act” of the A.T. — and all other NSHTs — is the National Trails System Act of 1968, as amended, which established the Appalachian Trail as a federal resource and outlined how the A.T. would legally interact with other federal and state conserved areas. It also clarified that private entities (such as the ATC) are allowed to participate in operating the Trail and managing the land. Three sets of amendments to that Act — two in 1978 and one in 1983 — kicked off the “Acquisition Era” of the A.T., advancing the legal relationships and division of roles between volunteers, the agencies, and the ATC, and clarifying that A.T. volunteers, the ATC, and the Clubs are permitted to do a wide range of activities in support of our cooperatively managed resource.

With the ATCA, we are hoping to harden successful conventions while retaining flexibility on the A.T. and throughout the National Trails System. Periodic reaffirmations and updates to laws are often necessary to ensure adherence, and the ATC is proud to use its anniversary to strengthen the legal framework for all NSHTs.

-

1946Administrative Procedures Act

Ensures the way in which regulations are made and requires opportunity to incorporate feedback. This statute is vital for all kinds of A.T.-related topics, such as commenting on forest plans and informing agency policy on volunteers.

-

1964Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) Act

The Land and Water Conservation Fund Act made it possible for federal and state agencies to secure the publicly owned lands that form the majority of the Appalachian Trail Corridor, complemented by additional conservation work done by land trusts and private partners.

-

1968National Trails System Act (NTSA)

The NTSA officially established the A.T. as the Appalachian National Scenic Trail and kicked off the process that created the complex and dynamic legal framework for its Cooperative Management System.

-

1969National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

A bedrock law for environmental policy, but not always environmental protection. The focus of the law is to ensure a “hard look” at governmental decisions by requiring a process to evaluate a variety of factors to encourage a decision that appropriately weighs them. ATC staff and volunteers are heavily engaged in NEPA work, including evaluating the impact of trail construction to wildlife and historical structures.

-

1969Volunteers in Parks Act

Foundational to the Cooperative Management System, it creates the framework by which volunteers are able to work on National Park System lands (and state lands for the A.T.), including workers’ compensation for injuries incurred while cooperatively managing the resource.

-

1976National Forest Management Act (NFMA)

The National Forest System was established to maintain multiple-use lands, serving conservation, recreation, and extraction purposes. The NFMA was enacted to establish a more orderly process for managing forests, including the creation of forest plans, in which the A.T.’s management areas and priorities are laid out for approximately 50% of the Trail in national forests.

-

1978NTSA Amendments

Pretty soon after the NTSA was enacted, it was clear that additional authorities and instructions would be necessary. The ATC worked with partners to have two sets of amendments to the NTSA enacted. One set, the “A.T. Bill,” authorized $90 million for the federal government to buy land connecting the national parks and forests already containing the A.T. The second expanded the National Trails System and established Comprehensive Plans as requirements for National and Scenic Trails. Our “comp plan” is the A.T.’s most important management document because it is the basis for all other federal and state land management plans for the Trail.

-

1983NTSA Amendments

The 1983 amendments to the NTSA increased the level of shareable responsibilities for volunteers and “volunteer organizations” (like the ATC). In particular, section 11 of the NTSA clarifies to the federal agencies that volunteers and volunteer organizations are allowed to do substantive work on and for our National and Scenic Trails. The ATCA seeks to pick up this thread by formalizing in statute what remain as informal and case-by-case treatments across national trails.

-

2020Great American Outdoors Act (GAOA)

The greatest conservation achievement in a generation, the GAOA “fully funded” the LWCF, meaning that every year, the full authorized amount of $900 million would be available to states and federal agencies. This, plus an administrative change at the National Park Service, meant that the state and federal governments could plan in advance to have money for land protection, rather than waiting to see whether and how much Congress made available each year. The GAOA also established the Legacy Restoration Fund (LRF), a temporary dedicated account to fund deferred maintenance projects on our public lands. The LRF needs to be extended, so please tell your Members of Congress you’d like them to do so!

-

2025

Appalachian Trail Centennial Act (ATCA) is reintroduced.

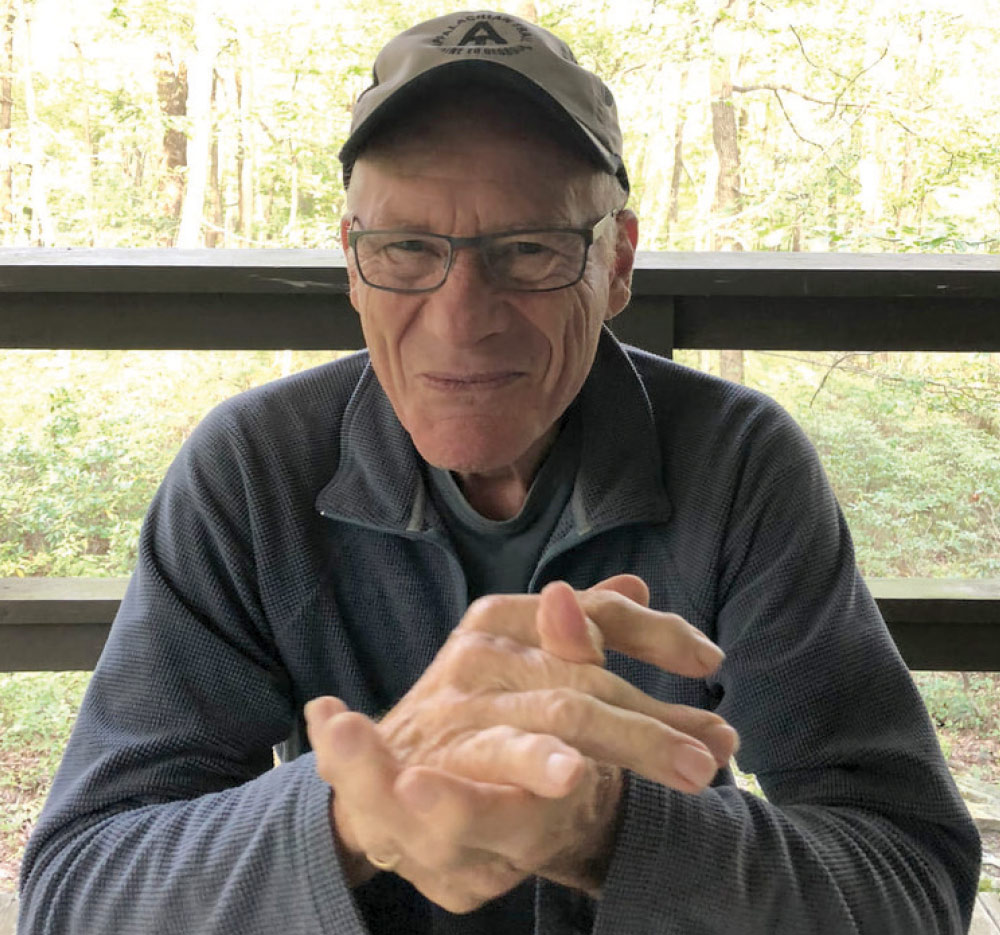

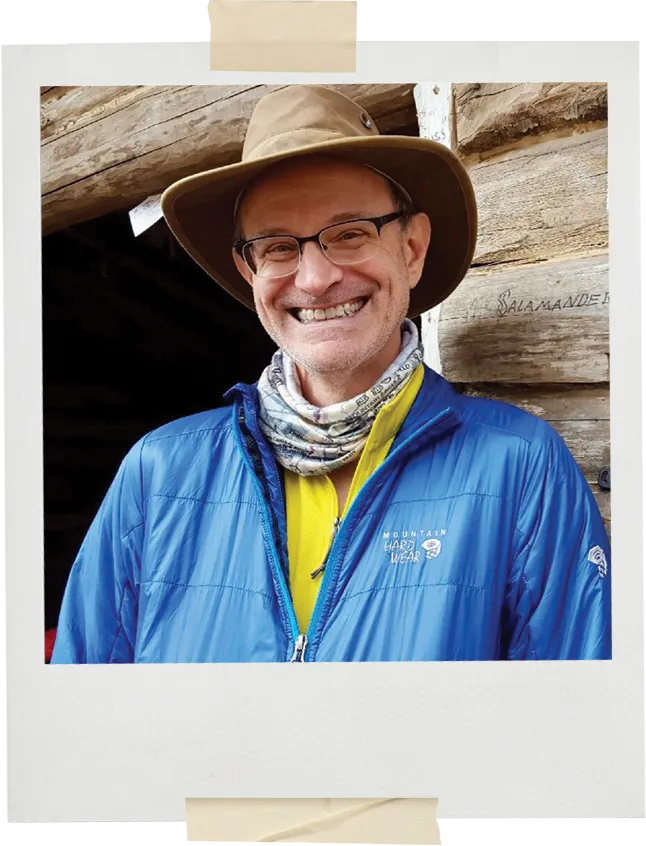

Chris Brunton — who has spent more than three decades working on and advocating for the Appalachian Trail — is one of the best sources on the Roller Coaster’s origin story. Brunton completed his hike of the A.T. in sections over 17 years, and was a volunteer with the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC), serving in multiple roles including on trail crews. Brunton and his wife, ATC President and CEO Sandi Marra, maintain a 3-mile section of the Trail north of Snickers Gap. They are also co-managers of the PATC’s Blackburn Trail Center.

Some months after the section now known as the Roller Coaster was opened in 1985, Brunton was looking at the logbook at the Blackburn Trail Center. “A hiker had written, That roller coaster today killed me,” he recalls. “And then a couple of weeks later, another entry had been added: You were right — that was a roller coaster, up and down and up and down. And then another comment. The name stuck.”

Why doesn’t the Appalachian Trail go around these rocks? Brunton explains that what created the Roller Coaster section was part of a decades-long process of moving the A.T. off the roads and privately owned land. This preserves the Trail for future generations and moves it away from roads, which improves safety for current visitors.

Photo by Sandra Marra

Brunton was among the handful of volunteers who built the Roller Coaster section. He and his co-leader, Bobby Lowery, did most of the preliminary work laying out where to put the trail, and then ran the crews. Lowery had thru-hiked the A.T. in the late 1970s, was a timber forester, and operated a sawmill in Round Hill, Virginia. As a chainsaw operator he cut and cleared all of the trees that had fallen across the route. After some weeks into the project the crew decided Brunton and Lowery needed trail names. They called Brunton “Trailboss” and Lowery “Treeslayer.” On July 14, 1985, a dedication was held at the Bears Den Hostel for the official opening of the new trail.

However, the trail work is never done. The post-pandemic boom in Trail users, especially day hikers, has resulted in new wear and tear on the footpath and the surrounding plant wildlife. Brunton and other volunteers continue to shore up rocks that have become exposed. “I’d say we see 200 to 300 people on a weekend day,” Brunton says of the day hikers. “In the thirty-plus years that I’ve been walking and working on the Trail, I’ve never seen these numbers of hikers.” His advice to visitors, new and experienced: “Enjoy the Trail. Leave no trace behind. Get involved — we can always use volunteers.”

What that “little” means to each hiker varies, and it has changed drastically over time.

Yet one item remains constant: the determination to take that first step and start their journey on the world’s longest footpath.

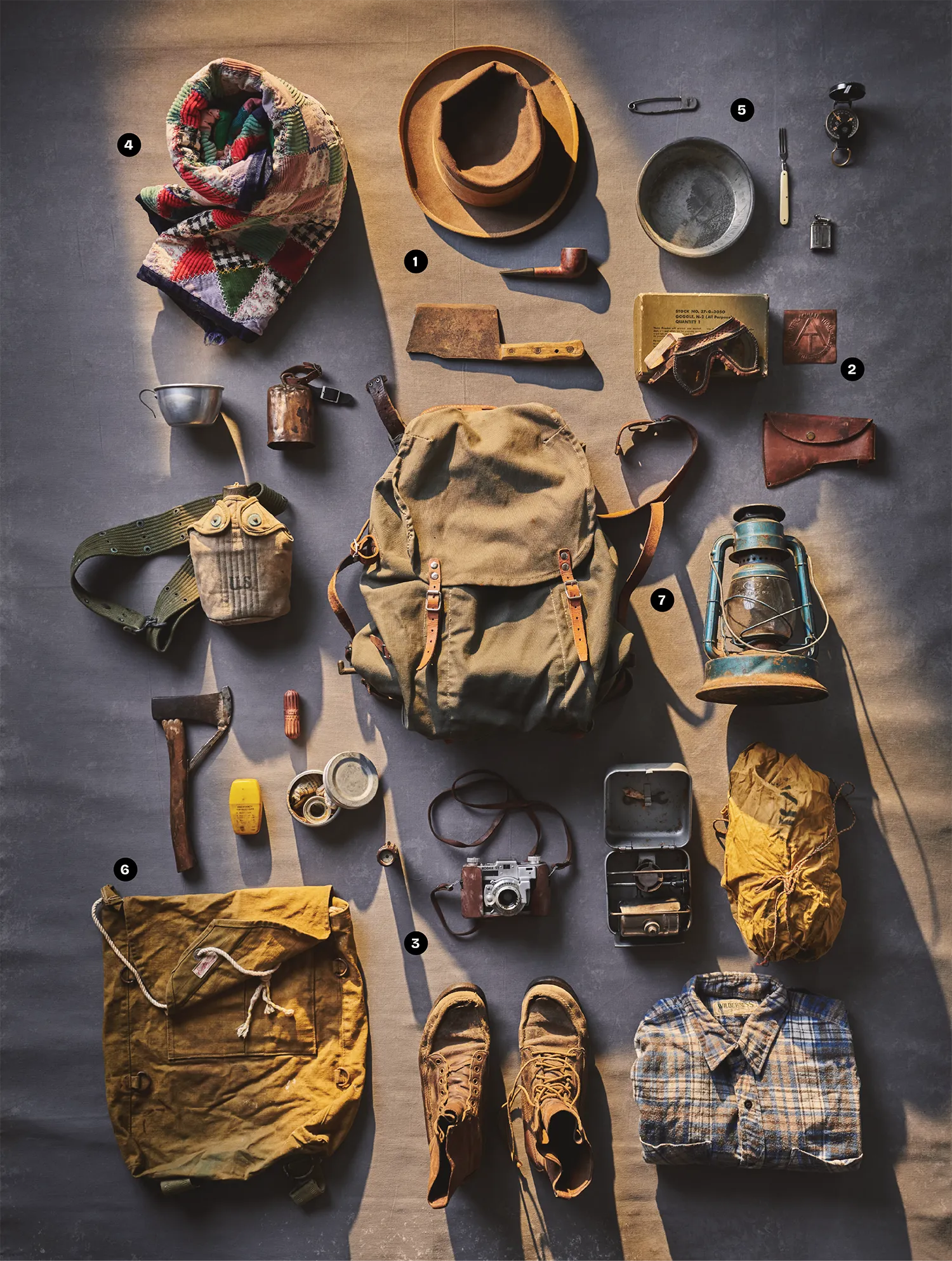

Thanks to efforts of the staff, volunteers, and supporters of the A.T Museum in Gardners, PA, artifacts like these are preserved for current and future Trail enthusiasts.

- The hat, pipe, and cleaver belonged to trail visionary Benton MacKaye (1879-1975). A community planner, forester, and dedicated conservationist, his 1921 essay in The Journal of the American Institute of Architects proposed the concept of the Appalachian Trail.

- Often referred to as the A.T.’s architect who made MacKaye’s dream a reality, Myron Avery (1899-1952) is responsible for measuring and marking much of the Trail, establishing trail standards, and assisting in land acquisition. Here you can see his goggles, leather sheath, and one of his essential tools on the Trail, an A.T. Marker.

- Earl “The Crazy One” Shaffer (1918-2002) is credited as being the first to thru-hike the Appalachian Trail, reportedly accomplishing this feat in 1948.* With his boots, flannel shirt, Kodak camera, compass, match holder, snake bite kits, hatchet, and U.S. Army canteen, he hiked the A.T. taking photos, composing poetry, and writing in his famous trail diary.

- This quilted blanket belonged to Emma “Grandma” Gatewood (1887-1973), the first woman to hike the Appalachian Trail solo.* According to her daughter Gatewood decided that if men could thru-hike, so could she. Grandma Gatewood completed her first thru-hike in 1955 at the age of 67, the second thru-hike in 1957, and section hiked the Trail in 1964.

- Ed Garvey (1914-1999) thru-hiked the Trail in 1970. His 1971 book, Appalachian Hiker, helped to raise awareness of A.T. thru-hiking and shared helpful information for fellow hikers. Garvey’s gear included his brass safety pin, plate, folding fork, compass, cigarette lighter, aluminum cup, copper bear bell, first aid kit, primus stove, and stuff sack. A trail builder and maintainer, Garvey was also a driving force behind the 1978 amendment to the National Trail Systems Act.

- Jean Stephenson (1892-1979) was instrumental to the Appalachian Trail becoming a national recreational resource. As an A.T. advocate in the field, Stephenson performed essential trail work in Maine — carrying some of her gear and notes in this backpack. She was the founding editor of the Appalachian Trailway News and authored several Trail guidebooks and publications. As Myron Avery’s second-in-command at the Appalachian Trail Conference, after his death in 1952, she served as the acting chairman until his successor was chosen.

- While the owners of this lantern and backpack are — as of now — unknown, it’s not hard to imagine a hiker in the mid-1900s using the light of the kerosene lantern to search through their pack as they set up camp for the night.

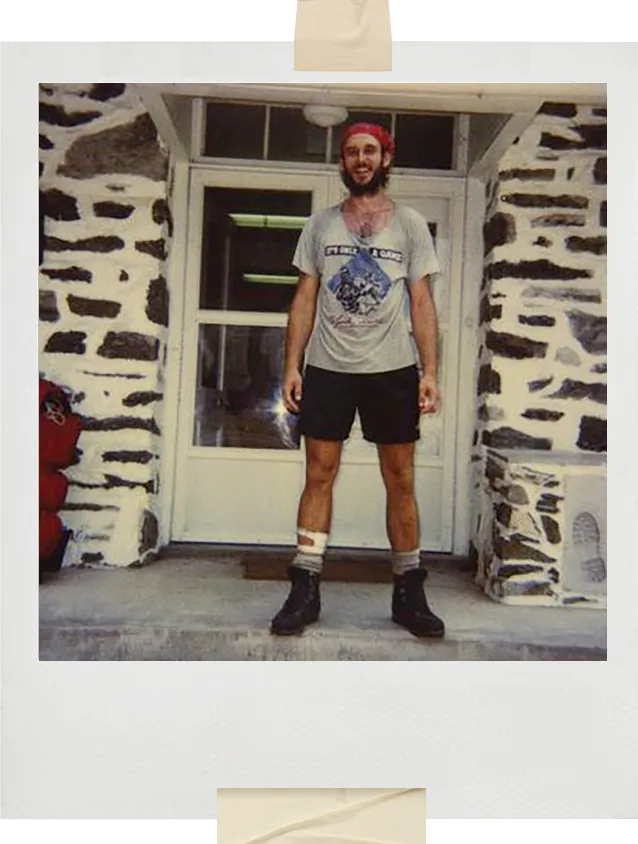

Shaffer’s story continues to inspire hikers and veterans alike, including Sean Gobin. Gobin’s service in the Marine Corps included three combat deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan. For twelve years, he had been called Lance Corporal, Lieutenant, and finally Captain Gobin, and wanted to learn what it would be like to be called by just his first name. So he chose “Sean” as his trail name and quite literally walked into a new chapter of his life in 2012. He began his thru-hike after receiving his discharge papers, “I drove out of the back gate of Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, drove to Springer Mountain, and started hiking. And what turned out to be just a personal bucket list item ended up honestly saving my life.”

Photo by Briana Apgar

Sean had been posting updates of both his mileage and his improved well-being via social media. His posts caught the attention of Appalachian Trail Conservancy Board members Rich Daileader, Bill Plouffe, and Clark Wright. The trio was looking for ways to honor Shaffer’s legacy. They were captivated by the parallels to Sean’s story, affirming the relevance of their desire to connect veterans with the Trail. After Sean’s successful summit of Katahdin, Daileader approached Sean for a meeting.

The team worked quickly that winter and Warrior Expeditions supported its first cohort of veterans in the spring of 2013. The nonprofit receives over 400 applications and gives scholarships to 40 veterans annually. Each year, the organization provides training, gear, and community support to help approximately 20 veterans hike the A.T.

The impact is profound, with participants reporting significant reductions in depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress. Perhaps it is not possible to completely walk off the war. But this partnership encourages veterans to walk forward into more healed versions of themselves.

of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and look to the next century of stewardship, the features included in this special commemorative issue explore momentous achievements dating back to 1925, insights into the history and evolution of the iconic A.T. blaze, and stories about the individuals who made — and continue to make — the world’s longest footpath possible.

Join us as we honor the many, the millions, who keep the Trail alive.

Photo by Benjamin Williamson

The resolution adopted the next day by those 21 men and one woman stated the objective somewhat differently: “to promote and establish the Appalachian Trail as a working, functioning service, as a system of camps and walking trails for rendering accessible to campers and walkers the mountains and wild lands and areas of the eastern United States, such service to be developed as a means for stimulating public interest in the protection, conservation, and best use of the natural resources within such areas.”

That ATC purpose statement was a bit more expansive than a prescient one for the now-social Trail on an unsigned, pre-1925 onionskin paper that more closely reflected MacKaye’s thinking: “The purpose of the Appalachian Trail is to stimulate … an ‘outdoor culture.’ This means the study of nature. And, it means the study of man. It means the study of man’s place in nature.”

These days, most hikers take those 80,900 white blazes for granted, but when the A.T. project began in 1921, the white blaze was not the symbol hikers followed up and down the Trail. At first, the Trail was little more than an idea and a cluster of disconnected sections of trail, largely utilizing existing trail networks. It’s likely that local trail authorities and Clubs simply put up signs designating this or that section of a trail as the “Appalachian Trail.”

Then, in 1923, a group of A.T. founders, including William Welch, Benton MacKaye, Raymond Torrey, Harlean James, and several others, met in Harriman State Park in New York. They agreed to use a copper marker designed in the machine shop at the park. Those first markers said “Appalachian Trail. Palisades Interstate Park Section” and quickly went into use between the Hudson and Delaware rivers. The markers also used the now familiar A.T. logo.

Conservation

Photo by Benjamin Williamson

Photo by Tracy Lind/ATC

The proximity of bears and hikers means the potential for human-bear interactions and conflict also increases. Additionally, bears have become habituated to humans — especially to human food.

Tradition

That Endures

Photo by Ben Earp Photography

Often unseen is the work of stewarding this singular footpath and making it an enriching experience for millions of visitors each year. But there is a remarkable, coordinated system that runs throughout the 2,190-plus miles of the A.T. It’s one that operates year-round, during the prime hiking seasons of late spring and early fall and through the months in between.

Hawk Metheny, Vice President of Trail Management for the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), describes this shared stewardship approach as “the most practical way to manage a long-distance trail. The collective effort of organizations working across the length of the Trail ensures that it is continuously cared for from one end to the other.”

The ATC’s Next Generation Advisory Council also held its annual meeting concurrent to the VLM100. In addition to NextGen Council members guiding VLM planning and leading sessions, the team also spent valuable time deepening relationships, experiencing the Trail on a night hike, connecting with the ATC’s leadership, and reviewing and making recommendations to their council’s charge.

The final night of the meeting culminated in a birthday celebration that brought out the childlike spirit in every attendee. To mark the ATC’s 100th birthday, there was a decades-themed costume contest challenging everyone to wear their best gear from any decade of the A.T.’s existence. A lively string band strummed in the background as the hall filled with chatter and laughter. Some volunteers donned their full work gear — a comical sight outside of the woods — while others showcased their historical knowledge, dressing as influential Trail figures like Grandma Gatewood.

Beyond the workshop sessions on how to care for the A.T., it felt important to put our feet on the Trail, too. The NextGen Council collected headlamps and driving directions to the nearest gap for a night hike! A joyful spirit overtook the group, and I felt grateful to share this memory with friends I rarely see in person.

When we arrived at the trailhead, my eyes took a second to adjust to the overwhelming darkness. Once we spotted the first familiar white blaze, the group giggled with anticipation. Throughout the walk, we traded hiking stories and penned a message in a shelter log, reconnecting with the trail culture that inspires us to protect and advocate for the A.T. This spontaneous hike reinvigorated our members and reminded us to find our own unique place in the Trail’s history — an act made possible by returning to this space of connection, wonder, and hope for the future.

Photo by Abbie Rowe/U.S. National Park Service

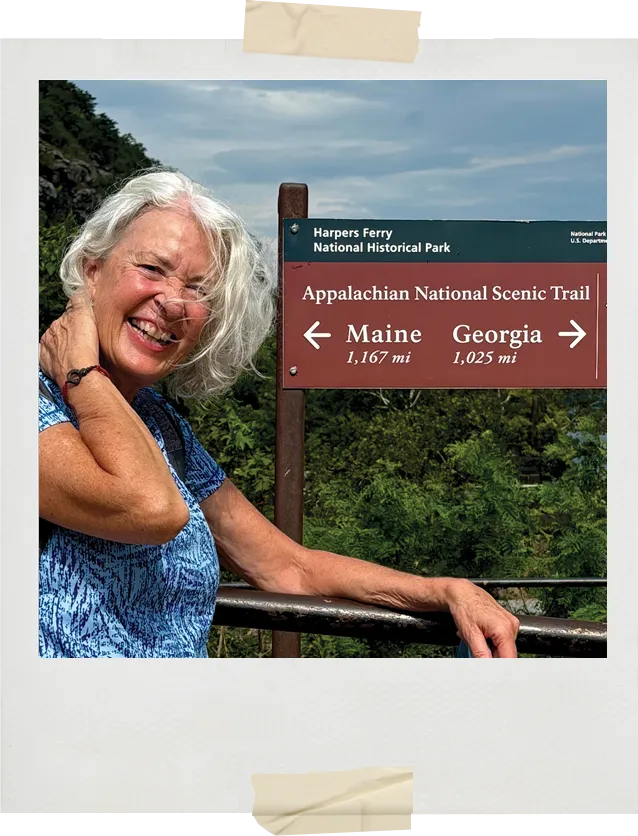

Serving as the hub of these connections are the ATC’s three visitor centers located in Virginia, West Virginia, and Maine. Each center is staffed by Trail experts with deep connections to the region and within Trail communities. For many hikers, visitors, and tourists these centers serve as their one — and in many cases, sole — point of contact.

Photo by Allyson Lance

Photo by Rachel Lettre/ATC

PHOTO BY SARAH ADAMS/ATC

COURTESY OF THE PATC

COURTESY OF SCA

PHOTO BY JUNKO TANIGUCHI/SOUL TRAK

PHOTO BY QUINN RITTER/PAOC CREW LEADERS

Photo by sarah jones decker

I believe that to truly know where you want to go, you must know where it is you have come from. The history and milestones reached by the ATC are key to that. One particular milestone that stands out in my mind occurred in 1981, when the Comprehensive Plan for the Protection, Management and Development of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail was signed. The Plan states:

“While the [sixty-year] history of the Appalachian Trail is, for the hiker, a story of varied landscapes, solitude, and challenge along a 2,100-mile footpath, it is also a record of a unique series of relationships which have provided stewardship for the Trail. The layout, construction, and maintenance of the Trail has been a shared effort of volunteer organizations, private landowners, and public agencies.”

The Comprehensive Plan goes on to define Cooperative Management and the importance of each participating organization — the three legs of the stool — in making this unique system.

The history of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy is the history of people agreeing to work together for a common cause, and 2025 has been a year of true cooperation. In the aftermath of Hurricane Helene and extending through an uncertain economic climate and many other challenges, the ATC has stood strong.

We have chosen to face each of these challenges and turn them into opportunities — ones that Protect the Appalachian Trail and its surrounding landscape, enhance the Experience for the millions of people who come to lightly touch or deeply immerse themselves in the A.T., and ensure that all individuals know and feel that they Belong on the Trail.

However, we can’t do this on our own. I would like to acknowledge the groups who work alongside the ATC’s Board of Directors, Executive Team, and dedicated Staff:

- Through the generosity of members and donors, the ATC has been able to extend its reach toward fulfilment of our mission.

- Without the tireless commitment of volunteers — including those from A.T. Maintaining Clubs, the Stewardship Council, Regional Partnership Committees, the Appalachian Trail Landscape Partnership, and the Next Generation Council — the Trail would not be the world-class resource it is today.

- Federal, State, and Local Governments and Agencies have long been and continue to be true partners in every sense of the word.

- The Appalachian Trail Caucus and members of the U.S. Senate have advocated on behalf of the A.T.

- A.T. Communities and Trail Angels welcome and support hikers along their journey and help look out for their safety and well-being.

- The visitors are vital to the A.T., choosing to spend their valuable time walking the ridgelines, valleys, pasturelands, balds, and wetlands of our iconic trail.

The last 100 years of the ATC have been a story of cooperation. What do we see when we look far into the future and envision what our legacy will be? We can’t know with certainty how our legacy will be shaped, but I do know that if we stand together and continue to cooperate in the fullest sense of the word, there is nothing we cannot do in service to our commitment to Keep the Trail Alive.

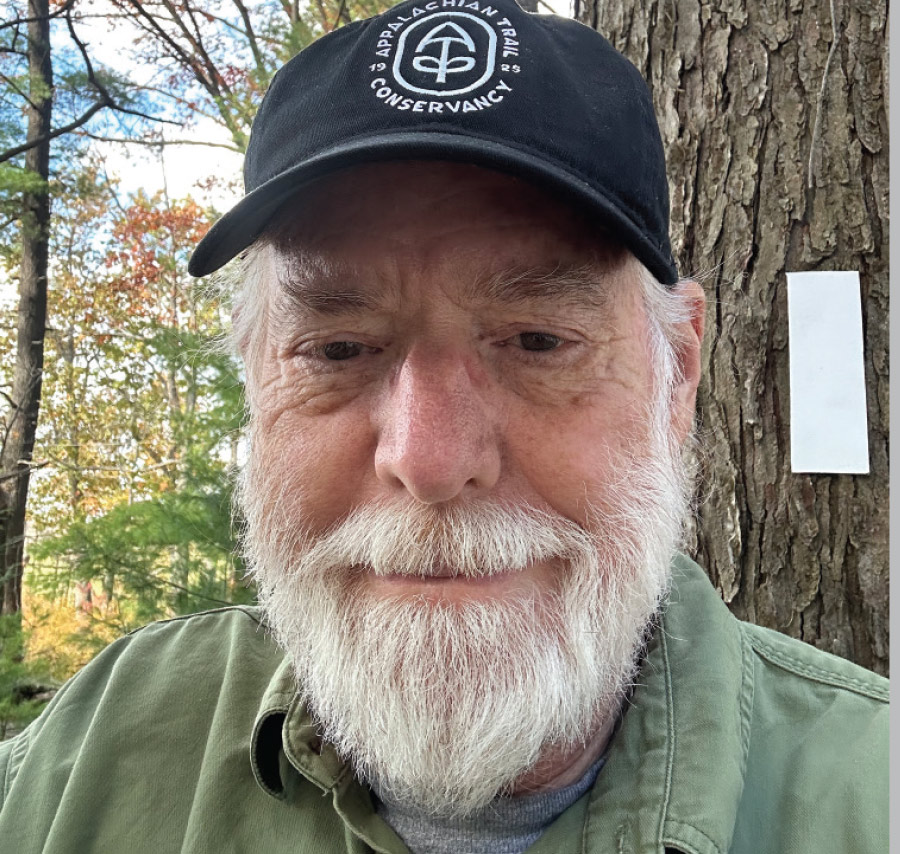

Jim LaTorre joined the ATC’s Board in August 2018. Over the course of his tenure, he has served as Board Secretary, Board Treasurer, Chair of the Governance Committee, and Chair of the Finance Committee. He has participated in Hike the Hill, presented at annual membership meetings, and completed his section hike of the A.T. in 2023. Hiking the A.T. led him to join the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club, where he serves as a District Manager, boundary monitor, and certified sawyer.

The Appalachian Trail is a very special ‘place’ — we wish the ATC continued success in their stewardship of an indelible and important pathway for our country.”

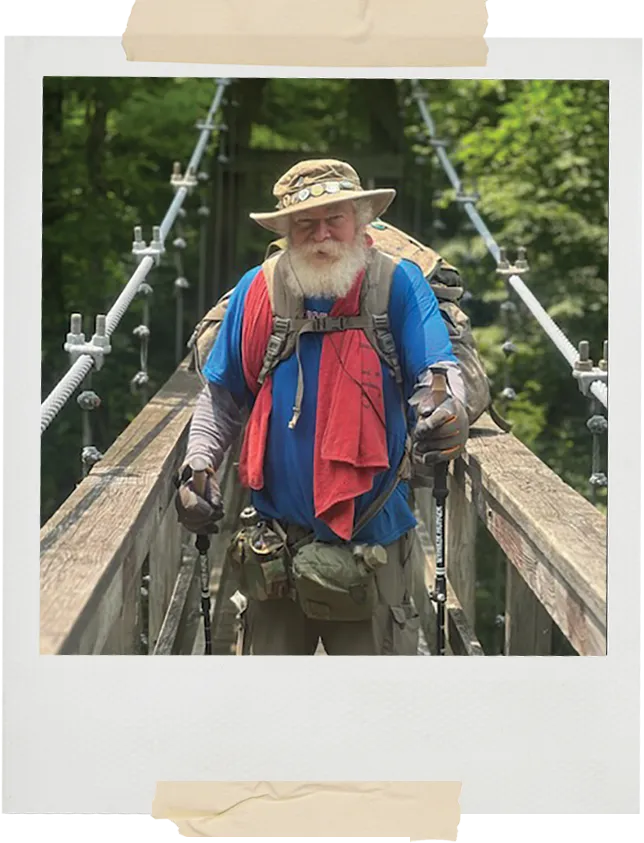

Each year’s journey brought me into a more intimate relationship with the Trail’s natural communities and challenges and realizing and appreciating the massive support provided by trail volunteers and the staff of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.

As a long-term ATC supporter, I have increased my level of support needed following the recent massive trail destruction due to Hurricane Helene in Western North Carolina and Virginia. I passionately encourage all trail users and conservation-minded others to manifest with their donations the legacy and mission of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.”

Over the course of five section hikes, Dr. Lee R. Barnes, Jr. completed the entire A.T. in 1976. He has been a proud Appalachian Trail Conservancy member since 1978. Throughout more than four decades of partnership, he has thoughtfully deepened his commitment to the ATC and recently joined the Benton MacKaye Leadership Society.

Through SAIC’s Connect & Grow Employee Resource Group, which focuses on professional development, community service and environmental stewardship, our employees actively support efforts that strengthen and sustain our communities.

We’re especially proud that Nathan Rogers, SAIC’s Chief Information Officer, serves on the ATC board, helping guide the organization’s mission to protect and manage the Appalachian Trail for generations to come. Together, we’re ensuring that this national treasure remains a place of inspiration, adventure and connection for all who experience it.”

Tragically, in 2021, one of their members — Jeff Hammons, a teacher by trade in New Mexico — died of a heart attack in South America while searching for rare birds with his son. In memory of their good friend and fellow thru-hiker Jeff “Kansas” Hammons and in honor of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s Centennial, several members of the Class of 1979 came together to raise more than $15,000 to support the A.T. They include Daniel Howe (a past member of the ATC’s board of directors), David Brill (the author of As Far As The Eye Can See, one of the most popular A.T. books that has been in print continuously for over 30 years), Paul Phillips, Robin Phillips, Cynthia Taylor-Miller, Paul Dillon, and Jim Shaffrick.

We’ve focused on reducing barriers to recreation, helped create a more inclusive narrative of those who enjoy the A.T., and offered guidance on programs and policies to encourage membership, advocacy, and youth leadership. Over the years, the ATC has benefited from the wisdom of our members who share a commitment to improving the A.T. experience for all.

What we had not yet contributed was funding. Fundraising has never, and will never, be our primary role. But for the ATC’s Centennial milestone, we knew we wanted that to change. We are proud that the Council made a $1,000 gift, adding our names to those investing in the ATC’s future.

We do this to honor the past 100 years, and to ensure that voices like ours continue to be heard for the next 100.

As the Appalachian Trail Conservancy celebrates its 100th anniversary, we’d like to imagine what a logbook at this “100-year mile marker” in the Trail’s history would have written in its pages. For that, we’re leaving a blank page for you — the hikers, dreamers, volunteers, advocates, and all other members of the Trail community — to sign this special, virtual logbook for the generations of hikers who will walk the Appalachian Trail in the next century. Thank you to everyone who submitted entries for our 100 year logbook!

of the Appalachian Trail.

Photo courtesy of the ATC

What do you think the many hikers or Trail enthusiasts might not know about corridor stewardship?

DH: Around 99 percent of the A.T. is on protected land. When the Trail is not inside of a National Forest, National Park, or state land, it is on a relatively narrow corridor of land that was specifically set aside for the A.T. by the National Park Service. In Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee, the A.T. is within National Forest lands and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. So all A.T. Corridor land (where we maintain the boundary lines) occurs from Virginia northward through Maine. On average, the A.T. Corridor is 1,000 feet wide (500 feet on either side of the Trail), and in some places it is much wider. Over 250,000 acres have been protected, and that number continues to rise as land acquisition continues.

A well-marked boundary shows everyone where the line is and enables corridor monitors to identify when an incompatible land use takes place within the corridor. Corridor monitors act as representatives (or ambassadors) for the A.T., and the way that we interact with our neighbors lets people know that we care a lot about the protected land.

GF: External threats to the corridor and encroachments can have noticeable impacts to visitors since the A.T. is hemmed into this narrow corridor. It takes a tremendous amount of work by volunteers and staff to monitor and maintain this boundary and, when we find them, to mitigate encroachments.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE ATC

DH: Boundary lines may look like a straight line on a map, but they traverse a wide variety of conditions on the ground and can bring you to places that others rarely visit. Surveyors blazed every tree within 3 feet of the boundary lines with yellow paint, and they marked every change in direction (what we call a corner) with a metal survey marker called a monument. Long, straight boundary lines are marked with intermediate monuments at regular intervals — 500 feet in every state but Maine, where the monuments are 1,000 feet apart.

Corridor monitors visit their section every year, and maintenance is done on a 5-year rotation. We maintain the line by repainting every blaze, clipping brush to keep the line visible, checking and reinstalling signs where necessary, and uncovering every monument. All monitoring and maintenance reporting is recorded on a very detailed online map, accessed by a GPS app that helps monitors navigate through the forest. There is something special about walking the line through the middle of the forest, where few people ever go. You notice a lot, and it seems like each visit reveals something new: interesting mushrooms, old stone walls, cellar holes, animal bones, edible plants, birdsongs, insects, ancient trees, etc.

JS: [Discussing the effort required to maintain monuments] During a boundary maintenance trip in Wind Gap, PA, a Batona Hiking Club volunteer and I located a monument low in a rock pile. We discovered the monument was loose but otherwise undamaged. We refreshed the paint on the rocks to help us find it the next time we visit. I also got the compass bearing for a new witness tree that we established to ensure that the monument had three reference points. (See photo)

Are there memorable experiences in the field that you’d like to share?

DH: I think what is most memorable is the people I’ve gotten to know while working in the woods. Boundary maintenance has a steady pace that allows for friendly chitchat and shared wonder at the intricacies of the natural world. It’s fun to learn from folks who have done this for a long time, show the work to new people, and to see how people progress. There is a definite shared sense of accomplishment when we puzzle out a difficult-to-find monument and literally dig where our measuring tapes form an “X,” uncovering a monument that has been buried by leaves and newly formed soil.

GF: In December 2019, a Land Stewardship & Natural Resources Manager and I were working with NY-NJ Trail Conference volunteer Moe on Bellvale Mountain, near the NJ-NY border. We had microspikes on to traverse snow with an icy crust. The temperatures were in the teens and 20s, and we had foot warmers stuck to our paint bottles to keep them flowing.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE ATC

DH: For volunteers, I would suggest they get involved with their local Trail Maintaining Club. Each Club coordinates their corridor monitors and assigns sections to visit every year. Group work days are scheduled for sections needing boundary maintenance. Anyone is also welcome to reach out to the ATC staff in their region if they would like us to introduce them to the Club member coordinating the boundary work. The ATC also occasionally hosts work trips in partnership with the local Clubs and other partner organizations, such as the Appalachian Long-Distance Hikers Association, the American Hiking Society, or Wilderness Volunteers. It’s a good way to get a large group together coming from all over to camp, work, and share meals and campfires.

I learned about camping, hiking, and the A.T. through scouting, and I recall my first visit to the A.T. on a chilly fall campout at the Tom Leonard shelter in Massachusetts. I went to college for Environmental Science, and one of my first jobs after college was as a seasonal Natural Resource and Land Stewardship Technician for the ATC in western Massachusetts. I was lucky enough to return to the ATC full time after graduate school, and I’ve been here ever since.

GF: I thru-hiked in 2013 and found the hardest part of that walk was figuring out what to do next. At first I didn’t look for work on the A.T., thinking it would be too much to watch hikers passing me by and that I’d eventually wander off with them. Then I stayed close to the Trail anyway, doing odd jobs while looking for my next long-term employment. In 2016, I conceded that if I was remaining near the A.T. anyway, maybe it wouldn’t be a bad idea to apply for work on the Trail. I was hired for the spring corridor stewardship field season in the Mid-Atlantic — the first of an almost continuous string of seasonal work around the A.T. corridor — until I landed in my current year-round role.

What are your hopes for the ATC and the Trail for the next hundred years?

GF: I hope for expansions to the corridor stewardship program to include more land management within the corridor — the removal of invasive species, habitat improvement, and whatever else we can do to improve the forest health.

DH: I’d like to see the ATC continue to grow its Science and Stewardship program so that we stand out not only as a spectacular recreational resource, but also as a model for land stewardship and ecological resilience. The protected land within the A.T. Corridor contains some remarkable rare species and the way the land is all connected provides a migratory pathway for many fauna and (on a longer timeline) flora. I think we can continue to grow the corridor and our program of protecting it, both on the boundary lines and in the ecosystems it contains.

I have seen a lot of changes over the years, worked with many people, and have made some lasting friendships. The changes in technology have been enormous. From outsourced systems, then some in-house systems, and now to the cloud. Name change and new logos. When I stop and think about all the changes that I have been through, it is hard to believe.

Some of my fondest memories are when I talk to members about their memberships and they tell me stories about being on the Trail. It is the best.

I am looking forward to seeing what the future will have in store for the ATC.

The A.T. changes people for the better. Gazillions of people love the A.T. That makes me hopeful for the Trail’s future. The two best things about working at ATC have been the great people I’ve had the opportunity to work with: A.T. volunteers, our agency partners, and ATC staff, and helping with all aspects of designing, building, maintaining, managing, and protecting a National Park. I helped build and manage one of the most popular national parks, a great honor!

- Traci Anfuso-Young is a freelance graphic designer, business owner, and adjunct professor who brings more than 35 years of experience in publishing to A.T. Journeys. She began her design career in 1989 at Backpacker magazine and later became Art Director of Mountain Bike magazine. In 2002, she launched her own business, TLA Design Studio, and became A.T. Journeys Graphic Designer in 2010, then Art Director / Designer in 2020. Through her fifteen years of work with the ATC, she says, “I’ve been able to apply my passion for design and visual storytelling, while connecting with the optimism and adventure of those who traverse this Trail. Congratulations to the ATC for its tireless work to safeguard this National Treasure for all. I look forward to the future, knowing the playground we call home is a shared partnership in purpose — one that unifies humanity and brings the joy, inspiration, and healing that nature and the Trail can provide.”

- Karen Ang has spent the last 25 years as a professional editor and writer. Whether it’s books, magazines, encyclopedias, or just about everything in between, her goal is to help the material inform, educate, and inspire. “That’s not hard with a project like A.T. Journeys,” she muses. “The amount of knowledge the ATC folks are happy to share and the passion everyone related to the Trail has for it is really remarkable. It’s great to collaborate on a publication that expresses this enthusiasm for the Trail through thoughtful storytelling and amazing photos. I grew up about 30 minutes from the A.T. and still kind of regret missing out on the big fifth-grade field trip to hike it … nearly 40 years ago. At least when I go back to hike in that section, I have a deeper appreciation for the Trail and am much better informed — if not as spry.”

- Briana Apgar is an ATC Next Generation Advisory Council member. Her career focus is health equity and community resilience. Apgar holds an MBA from the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business and a Master of Public Health from Virginia Tech. She’s currently pursuing her Doctor of Public Health at Tulane University.

- Elizabeth Choi is a content writer and editor who works on commercial marketing projects relating to ESG (environmental, social, and governance) compliance, artificial intelligence, and business entity compliance. Previously, she worked for several publishing houses, including Merrell Publishers and Antique Collectors Club. Living in Brooklyn, New York, allows Elizabeth to reach the A.T. solely by public transportation.

- Sarah Jones Decker lives in the mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee. Sarah has her MFA in Photography from Savannah College of Art & Design and a BA in Journalism and Creative Writing from Virginia Tech. She is a certified sawyer and trail maintainer with the Carolina Mountain Club and maintains Spring Mountain Shelter. Her first book, The Appalachian Trail: Backcountry Shelters, Lean-tos and Huts, documented all of the shelters on the Trail and her popular poster, The Crappalachian Trail (now a deck of cards!) continues to be her best seller. She is currently writing and photographing for her next book, 100 Classic Hikes of North Carolina, with Mountaineers Books. sarahjonesdecker.com.

- Jeffrey Donahoe moved to Washington, D.C., 40 years ago and has since done a considerable amount of day hiking in nearby areas, including the A.T. at Harper’s Ferry. Other favorite hiking spots include the Adirondacks, California, and in England’s Lake District. His dream U.S. hiking trips are Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks.

- Katie Eberts is an artist/illustrator from Cedarville, Michigan. A graduate of the University of Michigan’s Stamps School of Art & Design, she brings humor, whimsy, and a love of everyday magic to her work. Her illustrations have appeared in Bon Appétit, Taproot, Brio, The Washington Post Magazine, and of course AT Journeys. She’s the co-Illustrator Coordinator for SCBWI Michigan and the artist behind Fresh Made Simple and Hush-A-Bye Night/Goodnight Lake Superior. Follow her on Instagram @katieebertsillustration.

- Heather B. Habelka is a Connecticut-based freelance writer. In addition to writing feature articles for A.T. Journeys, she has been published in Connecticut Magazine, The Boston Globe, Hartford Courant, Connecticut Post, New Haven Register, and Costco Connection Magazine. She is a member of the American Society of Journalists and Authors and the Society for Features Journalism.

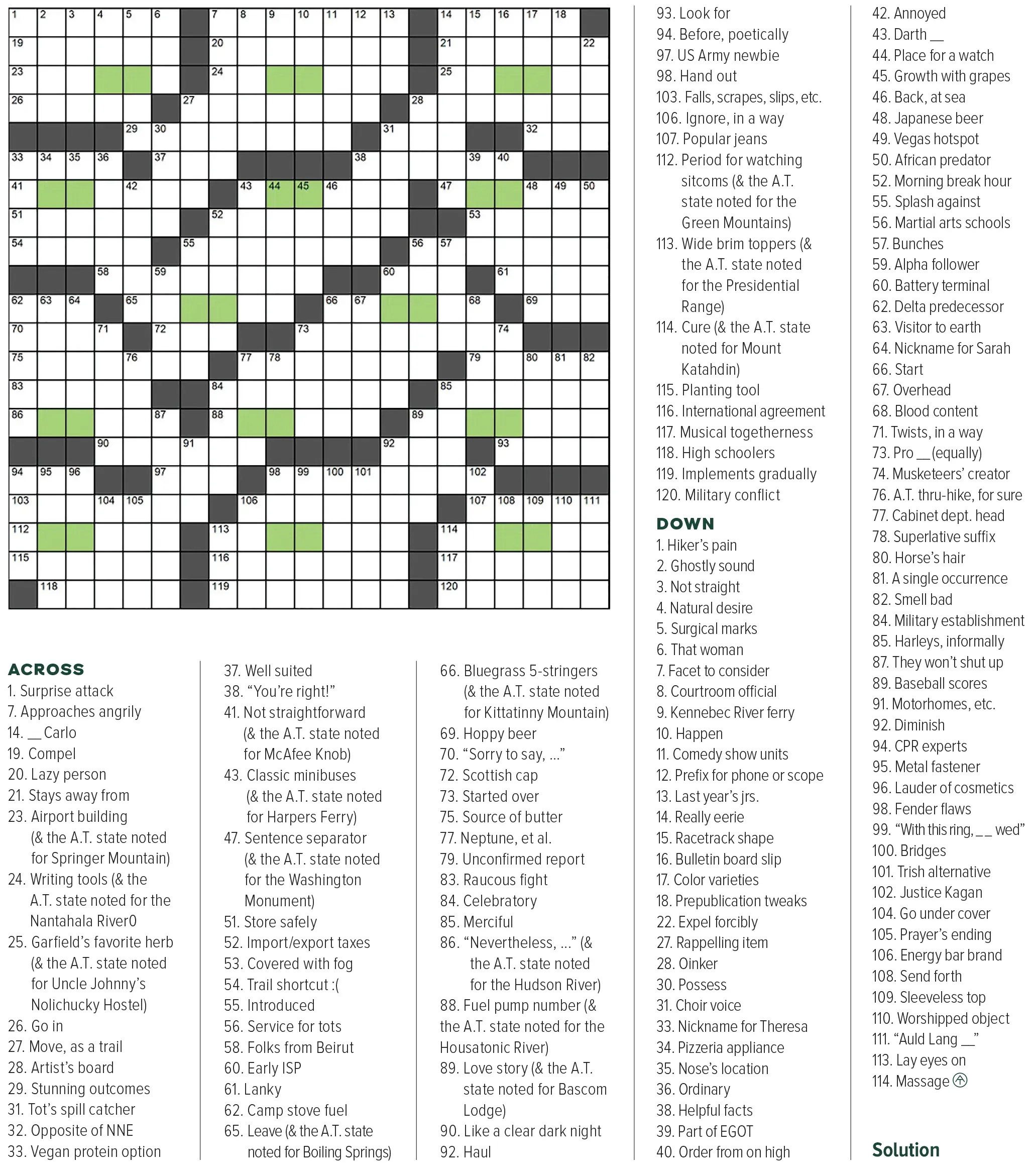

- Mark McClain of Salem, Virginia, is a professional crossword puzzle constructor whose work has appeared in 30 different outlets. He is a life member of the Roanoke Appalachian Trail Club and has hiked sections of the A.T. in all 14 states.

- Judith McGuire thru-hiked the A.T. in 2007 and has been volunteering at ATC HQ since 2008. She was a member of the Stewardship Council (including serving as chair of the Land and Resource Protection Committee) for five years and was a trail maintainer for the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club.

- Leon M. Rubin hiked part of the A.T with his dad in the ’80s and then left the Trail behind for years. Today, he hikes and volunteers with the Georgia Appalachian Trail Club in Dahlonega, Georgia. Rubin is a freelance writer and retired public relations consultant. An Ohio native, he lived previously in South Florida and is married with three children, two grand daughters, a dog, and a passel of cats. He’s grateful to be able to write for A.T. Journeys.

- Photographers

Keith Clontz

keith-clontz.pixels.com

Chris Gallaway

horizonlinepictures.com

Jerry Monkman

ecophotography.com

Joshua T. Moore

joshtmoore.com

John Sterling Ruth

johnsterlingruth.com

Cynthia Viola

cynthiaviola.com

Benjamin Williamson

benjaminwilliamsonphotography.com